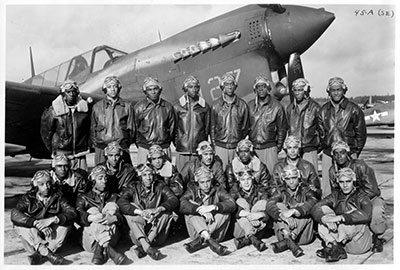

Histories of the US role in World War II frequently mention the famous Tuskegee Airmen, a segregated African-American fighter squadron that distinguished itself in the European Theater. Sometimes they also cite the 92nd Infantry Division (“Buffalo Soldiers”), which breached the Gothic Line in northern Italy. The 761st Tank Battalion (“Black Panthers”) occasionally appears too. The Black tankers fought their way with General George S. Patton’s Third Army from Normandy, across France, and deeply into Germany. But singling out these exceptional units does a disservice to the much more substantial role of African-Americans in World War II.

As the US National WWII Museum observes, “More than one million African American men and women served in every branch of the [segregated] US armed forces during World War II.” And millions more were active on the home front, building Liberty Ships and Sherman tanks and holding down thankless jobs in support of the war effort. In Half American, Dartmouth historian Matthew F. Belmont tells their stories, chronicling the time when the civil rights movement began to find its footing.

Estimated reading time: 9 minutes

Fighting for a chance to fight

As Delmont makes clear at the outset, “Nearly everything about the war . . . looks different when viewed from the African American perspective. For Black Americans, the war started not with Pearl Harbor in 1941 but several years earlier with the Italian invasion of [the African nation of] Ethiopia and the Spanish Civil War. As soon as Adolf Hitler’s regime rose to power in the 1930s, Black Americans recognized the significance of the Nazi threat and the similarities between the Third Reich’s and America’s racial policies.” Hitler’s ideology was, in fact, grounded in American and British racist theories, not German.

Yet, Delmont adds, “in the days after Pearl Harbor, hundreds of Black volunteers were turned away by military recruiters. In a nation mobilizing for war, African Americans first had to fight for the right to serve in the military.” And that fight only became less frustrating as manpower shortages forced the Pentagon to open the gates more widely later in the war.

Half American: The Epic Story of African Americans Fighting World War II at Home and Abroad by Matthew F. Delmont (2022) 400 pages ★★★★★

How African-Americans helped win the war

In his survey of the role played by African-Americans in World War II, Delmont highlights the essential work of the hundreds of thousands of Black men and women who did not fight on the war’s front lines. For example, in the course of the war, over 16,000 Tuskegee Airmen trained in Alabama. Fewer than 1,000 of those airmen were pilots, and out of them 352 were deployed and fought in combat. The 1,800 missions they flew over Europe were only possible because of thousands of others in the unit. The mechanics. Air traffic controllers. Mapmakers. Meteorologists. Typists. And, yes, no doubt janitorial staff, too. Yet this pattern was not unusual in the air corps. Nor was it out of synch with the armed forces as a whole. Overall, more than 16 million Americans served in the military during the war. Yet fewer than one million ever saw serious combat.

Speedy and efficient logistics make modern warfare possible

In fact, as Delmont makes abundantly clear, the greatest contribution made by African-Americans in World War II was in logistics. “Fighting a global war required a colossal logistical undertaking to link the continental United States to battlefronts around the world. On a map, these supply lines looked neat and orderly, so many air, land, and sea routes crisscrossing the globe. On the ground, it was clear that building, maintaining, and defending these supply lines entailed a tremendous amount of work.” And Black soldiers, sailors, merchant marines, and airmen performed much of this work. Throughout the war, the US military deliberately—as a matter of policy—assigned most African American soldiers and sailors to non-combat roles, sending many of those well-qualified for combat into jobs such as engineers, quartermasters, and cooks.

But logistics was key. For example, as Delmont reports, “In the six months after D-Day, the port of Southampton was the busiest in the world. More than 6,400 vessels left Southampton bound for France carrying nearly 2 million military personnel, 170,000 vehicles, and over 1.7 million tons of supplies. Black troops made up twenty-five of the twenty-seven port companies at Southampton, more than half of the truck companies, and almost all of its quartermaster and engineer general service regiments.” Without them, Eisenhower, Bradley, Montgomery, and Patton could never have moved as far or as fast inland as they did. And many of the generals acknowledged that debt in glowing terms following the war.

Fighting racism on the home front

It’s well known that the US military was segregated during World War II. That began to change only in 1948, when President Harry S Truman issued Executive Order 9981, desegregating the armed forces. (It was another decade before the order fully took effect.) But segregation on the home front presented massive problems throughout the war—and throughout the country, not just in the South.

When the United States first declared war and the nation’s major corporations began mobilizing to produce armaments, hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions of Americans flocked to factory gates to do their part in winning the war. African-Americans were prominent among them. But almost everywhere they were turned away. Racist managers and trade union leaders stoutly resisted allowing Black workers to join their ranks—and when African-Americans persisted, white workers frequently walked off the job. When massive pressure from grassroots action and government mandates eventually broke the logjam, Black workers usually encountered discrimination on the job. And that led to further tumult.

“I’d rather see Hitler win the war”

For example, as Delmont notes, “many Black war workers in Detroit used wildcat strikes to demand equal rights in defense plants. [A] Black strike at Packard ended after . . . three [African American] men were returned to their assembly-line jobs. Days later, on June 3, 1943, twenty-five thousand white workers (90 percent of the total workforce) retaliated by walking off the job, shutting down the entire plant. Many crowded the factory gates, cheering racist soapbox speakers. ‘I’d rather see Hitler and Hirohito win the war than work beside a n***** on the assembly line,’ one man screamed.” And although that was an isolated example, Delmont quotes many other examples of similar racist rhetoric elsewhere around the country. In fact, “Detroit was just one of more than 240 cities, towns, and military bases that witnessed outbreaks of racial violence in the summer of 1943.”

As one African-American war correspondent wrote so poignantly, Black soldiers fought to “tear down the sign ‘No Jews Allowed’ in Germany,” only to finding signs reading NO NEGROES ALLOWED were still commonplace in America.”

The civil rights movement began coming into its own in the war

Delmont’s story largely revolves around some of the millions of Black men and women whose work in World War II has never made the history books. But familiar figures appear, too.

- Labor leader A. Philip Randolph threatened a massive African-American March on Washington in 1941. His threat, backed up by the NAACP and other early civil rights leaders, forced FDR to issue Executive Order 8802, which prohibited discrimination in the defense industry.

- Thurgood Marshall, the future Supreme Court Justice, traveled tens of thousands of miles every year to lend his considerable legal skills to NAACP Chapters around the country.

- Lieutenant Colonel (later four-star General) Benjamin O. Davis Jr., a West Point graduate, led the Tuskegee Airmen. He was the first Black brigadier general in US history.

- Roy Wilkins, James Farmer, Rosa Parks, and others who would later rise to prominence in the civil rights movement were all active in the struggle for African-American equality during World War II.

Putting it all in perspective

Delmont observes, “It was only a few years ago that the Associated Press updated its style guide to encourage journalists to stop using the euphemisms ‘racially motivated’ or ‘racially charged’ when ‘the terms racism and racist can be used . . . to describe the hatred of a race, or assertion of the superiority of one race over others.'”

In the concluding words of his book, Demont reminds us that “if we tell the right stories about the war, we can finally honor the sacrifices of the Black veterans, defense industry workers, and citizens who fought on foreign battlefields and in their own cities and towns so that no one would ever again be treated as half American.”

About the author

Matthew F. Delmont’s bio at Amazon.com reads as follows: “Matthew F. Delmont is the Sherman Fairchild Distinguished Professor of History at Dartmouth College. A Guggenheim Fellow and expert on African American history and the history of civil rights, he is the author of Half American: The Epic Story of African Americans Fighting World War II at Home and Abroad (Viking, 2022), as well four previous books: Black Quotidian, Why Busing Failed, Making Roots, and The Nicest Kids in Town. His work has also appeared in The New York Times, The Atlantic, The Washington Post, and several academic journals, and on NPR. Originally from Minneapolis, Minnesota, Delmont earned his BA from Harvard University and his MA and PhD from Brown University.”

For more reading

For a superb novel about the experiences of African-American soldiers in combat, see my review of Miracle at Saint Anna by James McBride (Black soldiers on the front line in Tuscany in World War II).

Check out Good books about racism reviewed on this site.

You might also enjoy:

- 10 top nonfiction books about World War II

- Books about World War II in the Pacific

- The 10 best novels about World War II

- 7 common misconceptions about World War II

- The 10 most consequential events of World War II

- Top 20 popular books for understanding American history

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, plus a guide to this whole site, on the Home Page.