Estimated reading time: 6 minutes

Author William Gibson famously made the point that any science fiction story, no matter how far in the future it’s set, is really about the present. After all, no author can fail to reflect the prevailing values and preoccupations of their time and place. And that truth becomes abundantly clear when you reach back into the past to read (or re-read) the best of the genre’s Golden Age. A case in point is Walter M. Miller, Jr.’s classic dystopian novel, A Canticle for Leibowitz.

A book that reflects the nuclear hysteria of the 50s

A Canticle for Leibowitz appeared in 1959, midway through Dwight Eisenhower’s second term. But Miller was a short story-writer—Canticle was the only one of his two novels published during his lifetime—and the book was built on three short stories that came out in 1955, 1956, and 1957. Miller expanded and wove them together into the novel.

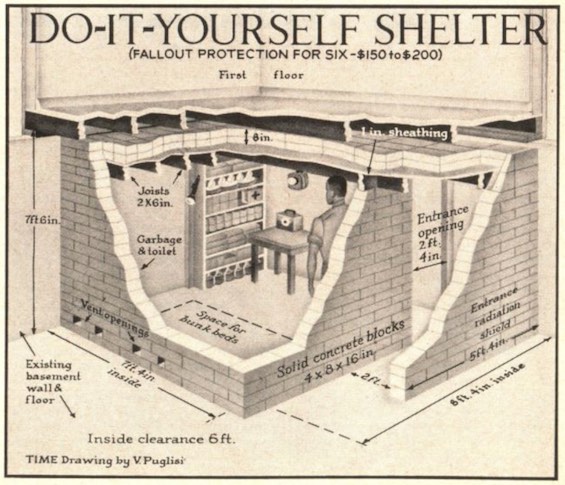

Those years saw the peak of hysteria about the prospects for nuclear war. The press was full of stories about nuclear fallout shelters (although only some 200,000 were ever actually built). Schoolchildren were taught to hide under their desks in the event of attack. And conservative zealots in and out of the Pentagon were speaking out about the survivability of nuclear war. So it’s no surprise that Miller would write a future history set in the aftermath of nuclear Armageddon. He was far from alone. Nevil Shute’s On the Beach (1957) and Pat Frank’s Alas, Babylon (1959) were just two among a flood of similar books.

A Canticle for Leibowitz by Walter M. Miller, Jr. (1959) 320 pages ★★★★☆

Winner of the Hugo Award for Best Novel

A future history spanning a millennium

In A Canticle for Leibowitz, we follow the history of the monastery of the Albertian Order of Leibowitz over the course of 1,200 years. The story unfolds in three chapters or “books.”

The 26th century

The first, “Fiat Homo” (Let There Be Man), opens in the 26th century. In the aftermath of a 20th-century nuclear holocaust, an electrical engineer named Isaac Edward Leibowitz had founded his eponymous order, wracked with guilt over his involvement in developing weapons for the Pentagon. A 17-year-old novitiate named Brother Francis Gerard chances upon the fallout shelter in the Utah desert where Leibowitz’s wife and fifteen others had died. The shelter is full of books and other documents that Leibowitz had stashed there in hopes of preserving humanity’s culture and history. Like medieval monks copying ancient manuscripts, the Brothers of the order have dedicated themselves to memorizing and copying what few intellectual vestiges remained of the past.

The 32nd century

Book two, “Fiat Lux” (Let There Be Light), advances the story by six centuries. The tiny village near the monastery of the Brothers of the Order of Leibowitz has grown into a town, and half a dozen or more warring principalities have arisen across the North American continent. The Brothers continue to guard the documents hauled out of Leibowitz’s fallout shelter, insisting that any of the tiny number of scholars who wish to study them must make their way to the monastery in the desert.

At length, one brilliant scholar, Thon Taddeo, manages to avoid the roving bands of bandits and mutant “monsters” to arrive there. Like Newton, Einstein, and a handful of others through the ages, Thon Taddeo has taken intuitive leaps in physics and astronomy far ahead of prevailing science. And one of the Brothers has built on his work on electricity to construct a manually operated generator to power an arc lamp.

The 38th century

“Fiat Voluntas Tua” (Thy Will Be Done) vaults ahead another six centuries to a world analogous to our own. Two global superpowers, the Asian Coalition and the Atlantic Confederacy, have been embroiled in a cold war for 50 years. The Brothers have cast off their anti-intellectualism but cling to the conservative Catholic views of many centuries past. They have broadened their mission to the preservation of all knowledge, not just the Leibowitz documents. As nuclear war threatens to break out, rumors persist that each of the two sides has already detonated one thermonuclear device. Then the Asian Coalition strikes the North American capital, Texarkana. More than two million die. Armageddon looms.

Conservative Catholic theology permeates the story

At the time Miller wrote Canticle, he was a devout Catholic. Most of the principal characters in the novel are monks, and their beliefs and actions reflect the traditional strictures of the Church in the years before Pope (now Saint) John XXIII and Vatican II. Even in the course of the third “book” of the novel, set 1,800 years in the future, the abbot of the monastery where most of the action is set demonstrates the zealotry of the most extreme Catholics of our era.

Miller later turned against the Church, casting the institution in negative terms in the sequel to this novel. And late in life he committed suicide, one of the greatest sins a Catholic can commit.

Miller’s intention to transcend the limits of science fiction is clear throughout. Dialogue and the private thoughts of the abbot in each of the three books reflect a serious inquiry into the mysteries of Catholicism. And an enigmatic figure appears in each of the stories—the immortal “Wandering Jew,” the man of legend who taunted Jesus on his way to the Cross and was condemned to wander the Earth until the Second Coming. It is he who points the way for Brother Francis to the Leibowitz fallout shelter and engages each of the abbots in debate.

About the author

A Canticle for Leibowitz was the only novel published in the lifetime of its author, Walter M. Miller, Jr. (1923-96). The novel won the Hugo Award in 1961. Miller was known primarily as a short story writer. A Canticle for Leibowitz had been published serially from 1955 to 1957, with each of the three “books” in the novel released separately. At his death (by his own hand), Miller left behind a sequel, Saint Leibowitz and the Wild Horse Woman, which was published posthumously the following year.

For related reading

For another celebrated science fiction novel in which the Catholic religion is the dominant theme, see The Sparrow by Mary Doria Russell (A troubled First Contact mission led by Jesuit priests). The author wrote the introduction to this edition of Miller’s novel.

For a history of the Church, see Ten Popes Who Shook the World by Eamon Duffy (Catholic Church history through the lives of 10 Popes).

For more good reading, check out:

- The top 10 dystopian novels reviewed here

- The ultimate guide to the all-time best science fiction novels

- 10 top science fiction novels

- These novels won both Hugo and Nebula Awards

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.