Two things are apparent at the outset of The Washington War in author James Lacey’s list of “The Washington Warriors.” First, many of the names are unfamiliar to most readers. Several certainly were to me. Some have never appeared anywhere else in my reading on World War II even though Lacey describes them as “FDR’s inner circle.” And, second, he pulls no punches, rendering such judgments as “he wasted his talent on revenge plots and petty jealousies” and “a man without friends or the desire to make any.” You’re not likely to find such characterizations in books by academic historians. And yet, despite the often unflattering comments about the players, it’s clear on reading further in the book that Lacey has told a story that is both central to gaining perspective on the war and far too often ignored.

Estimated reading time: 8 minutes

“Wars are won in conference rooms”

As the author notes, “Battles are won on the fighting fronts, but wars are won in conference rooms.” Lacey pokes his head into those conference rooms and examines the plans, memorandums, and correspondence among the politicians, the military brass, and the bureaucrats whose nonstop bickering and maneuvering for power shaped the course of World War II. It’s a fascinating tale and essential reading for anyone who seeks to understand how the Allies won. Because it’s clear in Lacey’s telling that the end was never foreordained.

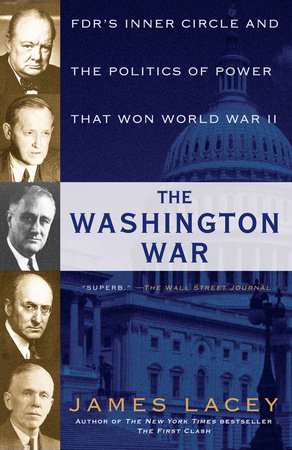

The Washington War: FDR’s Inner Circle and the Politics of Power That Won World War II by James Lacey (2019) 542 pages ★★★★☆

Office politics and bureaucratic wrangling in FDR’s inner circle

Most accounts of the Allied victory in the Second World War hinge on the titanic battles at Stalingrad, Midway, Normandy, and in the Atlantic. Lacey draws our attention instead to the “titanic rows” in Washington among the politicians and bureaucrats and military men—arguments that sometimes degenerated into shouting matches involving the American and British Chiefs of Staff, members of Congress, and the ill-prepared and sometimes incompetent bureaucrats heading the government agencies that proliferated under FDR. “By 1942,” Lacey notes, “so many [“alphabet agencies”] had been birthed—WPB, OPA, BEW, NWLB, etc.—that no one had any idea of what all the acronyms stood for, or for that matter what they all did.” It’s sometimes difficult to see who was calling the shots.

Even Franklin Roosevelt and Winston Churchill come across as erratic at times, with FDR portrayed as “the most Machiavellian of U.S. presidents” and the Prime Minister as obsessively focused on preserving the British Empire. You may wonder as you read all this how on earth the Allies ever won the war—unless you understand that the Axis powers blundered from one strategic error to another and defeated themselves in a war they should never have begun.

Did politics and maneuvering for power hamper the Allied war effort?

However, Lacey brings a charitable perspective to the scene he portrays. “My assumption when I began this book was that such fights hampered the war effort. But the more I delved into the clashes that made up the Washington war, the clearer it became that these titanic rows almost always led to better outcomes than would have prevailed had there been a single man or apparatus directing events.” But it’s hard to take that view in light of the two years’ lost in the struggle to amp up arms production and the Allies’ failure even to acknowledge the Holocaust until a third of Europe’s Jews were dead.

FDR’s inner circle includes unfamiliar names

All the usual suspects figure in Lacey’s account of the war behind the scenes. FDR and Churchill. Harry Hopkins. Marshall, King, Leahy, Stimson, Knox, Hull, and Welles. But other, far less familiar names crowd onto center stage, too. Among them were the following:

- Assistant Secretary of War Robert B. Patterson, “one of the great but forgotten men of World War II.” Lacey writes, “His single-minded ambition was to increase war production, and he was tough enough to force his will on most, which he did with reckless abandon.”

- Director of the Office of Price Administration Leon Henderson, who quickly became “public enemy number one” when he squelched demands for higher prices from business and higher wages from labor.

- Jesse Jones, chair of the Reconstruction Finance Corporation. In Lacey’s view, he “became a ‘one-man bottleneck’ whose stranglehold on the release of money was seizing up the nation’s nascent mobilization drive.”

- General Brehon Somervell, George Marshall’s aide, who “ran the logistics for the land and air war in both the Pacific and Atlantic theaters. He was a tough man in a job that required toughness, but his obstinacy almost single-handedly wrecked the nation’s nascent mobilization for war.”

- William Jeffers, “who came to do a job—rubber czar—accumulated the power necessary to do it, and then gave it up when the job was done.”

- Budget director Harold D. Smith, whose “inspectors were so feared that they became known as Roosevelt’s Gestapo.”

- And “three of the war’s most unlikely heroes: Simon Kuznets, Robert Nathan, and Stacy May.” Economists and statisticians, they began the job of mapping America’s industrial capacity years before the war and produced a game plan that eventually pointed the way toward fulfilling FDR’s promise to arm and supply the Allies.

Mobilization was slow

Historians celebrate the extraordinary productive capacity of the American economy in most accounts of the war. In The Washington War, by contrast, Lacey details the chaotic and counterproductive bureaucratic infighting and political meddling that got in the way of mobilization. Power politics in FDR’s inner circle prevented the country from fulfilling the promise of the Arsenal of Democracy for more than two years following his storied speech on December 29, 1940. In the author’s account, it becomes clear that production of war materiél only went into high gear when former Senator and Supreme Court Justice James F. Byrnes took charge of the Office of War Mobilization in May 1943. In that capacity, Byrnes effectively functioned as deputy president in charge of domestic affairs, freeing up FDR to concentrate on the conduct of the war. Where necessary, he knocked heads together, something the President was never prepared to do.

Surely, more than seven decades after the fact, Lacey got some things wrong. His judgments of individuals may be flawed in some cases. He might have misconstrued the intentions of one or another of the figures he describes as central to the story, and possibly even in most. But the Big Picture he paints is an accurate reflection of the chaotic reality that prevailed in official Washington during the war years. Because FDR wanted it that way. The President made an art of setting up rival power centers around himself—so that no one could gain the power to threaten him. In fact, it’s surprising that he finally acquiesced to the appointment of Justice Byrnes to the Office of War Mobilization in 1943. Until it became unavoidably clear that the mobilization was badly lagging, and his own health began growing worse, did he take that step.

About the author

James Lacey teaches at the Marine Corps War College and works as a military analyst for the Institute for Defense Analyses. His publisher notes that “He is a widely published defense analyst who has written extensively on the war in Iraq and the global war on terrorism. He served more than a dozen years on active duty as an infantry officer. Lacey traveled with the 101st Airborne Division during the Iraq invasion as an embedded journalist for Time magazine, and his work has also appeared in National Review, Foreign Affairs, the Journal of Military History, and many other publications. He lives in Virginia.

For related reading

For a different perspective on American mobilization for World War II, see Freedom’s Forge: How American Business Produced Victory in World War II by Arthur Herman (World War II: when America was united in common purpose).

You might also enjoy:

- 10 top nonfiction books about World War II

- The 10 best novels about World War II

- 7 common misconceptions about World War II

- The 10 most consequential events of World War II

- Top 20 popular books for understanding American history

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.