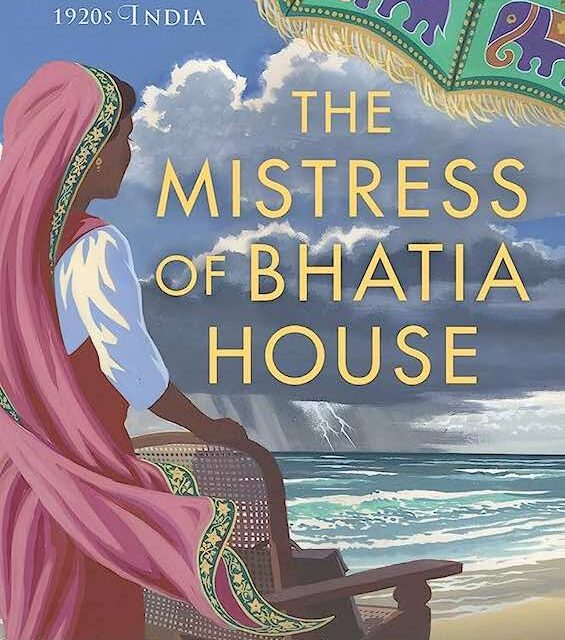

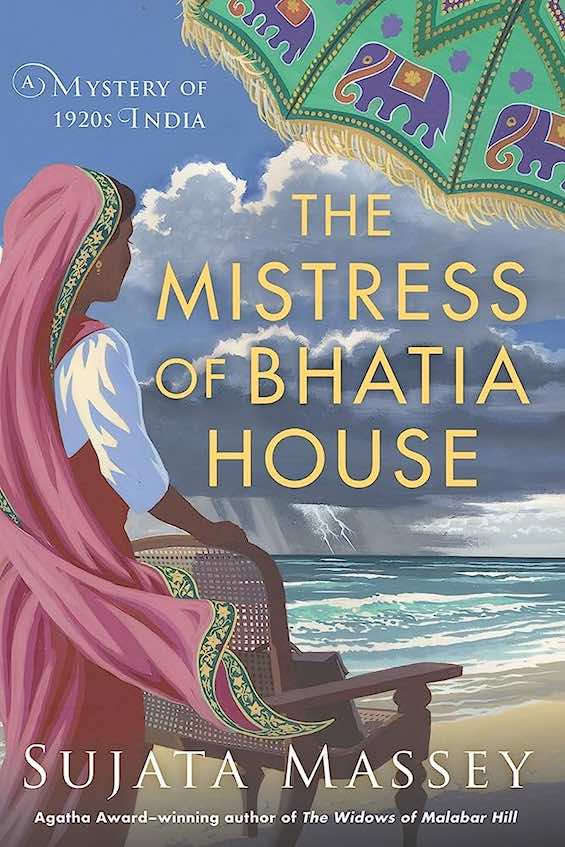

Read the first several chapters of Sujata Massey’s engrossing fourth entry in her series about the first woman lawyer in Bombay, and you’ll get the impression that the book is all about a falling-out between two sisters and the mistreatment of a young woman servant. But don’t be fooled. The story is slow on the uptake, but it will soon enough devolve into not one but several perplexing mysteries. And as the stakes mount, so too will the crimes. Arson. Government corruption. Rape. Attempted murder. And a murder that is all too successful. The Mistress of Bhatia House is a worthy successor to Massey’s award-winning series debut, The Widows of Malabar Hill. And it will leave you with haunting images of India 100 years ago.

Estimated reading time: 6 minutes

A guidebook to India’s diversity

Massey’s greatest strength as a writer is her ability to evoke the clash and tumult of life in India a century ago. Bombay then was not the megalopolis it is today, with more than 25 million people crowded into its teeming streets and lanes. In the 1920s, when the novel is set, its metropolitan population was 1.2 million. But it was no less diverse and chaotic. And that diversity leaps from the page in The Mistress of Bhatia House. The principal characters include Parsi attorneys. Hindu, Muslim, and Parsi business moguls. English colonials and police officials. A native-born Jewish woman gynecologist. A Muslim prince and his Australian bride. And Marathi, Gujarati, and Bengali servants speaking their mutually unintelligible languages. The novel reads like a guidebook to India’s endless diversity.

The Mistress of Bhatia House (Perveen Mistry #4) by Sujata Massey (2023) 432 pages ★★★★☆

An abundance of plots and subplots

The story is anything but simple, with numerous intertwining plot lines. Perveen’s sister-in-law, Gulnaz, has become paranoid and irascible after giving birth to her first child, and she has unaccountably turned against Perveen. (She clearly suffers from postpartum depression, a disease that wasn’t given a name until several years later.) Meanwhile, Sunanda, a young woman servant in the home of a wealthy family, has been arrested for committing abortion. When Perveen rushes to defend her, she collides with the English legal system’s prohibition on allowing women to address the court. (She’s not just the first woman lawyer in India’s largest city; she’s the only woman lawyer there.) But there’s more.

Perveen’s English friend, Colin Sandringham, has been hired by an English colonial official to redraw the map between a neighboring princely state and the Bombay Presidency—and turned up disquieting information. And Colin has given up his post in the Indian Civil Service to move to Bombay to be near her. They’re in love, but she can never marry him. (That’s a long story from an earlier book in the series.) While this is all going on, money is changing hands, and fortunes are on the line, in business dealings among the wealthy men, British and Indian alike, who surface in the novel. And believe it or not, there’s even more. This is a very complicated story.

India’s complex social dynamics

One hundred years ago India’s social dynamics were no less complex than they are today. The caste system was fully in place, of course, and much more in the open then than today, when caste discrimination has been nominally for a decade. And most portrayals of life in India, whether fiction or nonfiction, tend to focus on caste. It is, after all, what makes India stand out from other major countries. But in The Mistress of Bhatia House Sujata Massey demonstrates a deep understanding of the class dynamics as well. In some ways, class differences were even more consequential—and that’s clear from the novel.

- English overlords whose clubs deny entry to Indians, no matter how wealthy.

- Indian business moguls who live in palaces and exploit, and often mistreat, their household servants as well as their employees.

- Indian police officers and government officials who consider themselves a class above others and demand bribes to do their jobs.

- Servants whose positions in the household elevate them above others, effectively setting them up as a distinctive class.

- Not to mention the complicated interplay of religious differences in a system in which each major religion operated under its own law code. Separate law codes dealing with marriage, divorce, and adoption govern Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs, Jains, Buddhists, Parsis, Jews, and Christians—and they’re still in force today everywhere in India except the tiny state of Goa.

About the author

Sujata Massey has written fifteen mystery novels and won literary awards for most of them. Eleven are set in Japan, where she lived for two years working as an English teacher. Her most recent work are the four historical mystery novels to date in the Perveen Mistry series, the first of which was published in 2018. Massey was born in 1964 in Sussex, England, daughter of a father from India and a mother from Germany. She moved with her family at the age of five to St. Paul, Minnesota, where she grew up. Massey obtained a bachelor’s degree from Johns Hopkins University. She worked for a time after graduation as a reporter for the Baltimore Sun.

For related reading

I’ve reviewed all three of the previous books in this series:

- The Widows of Malabar Hill – Perveen Mistry #1 (The first woman lawyer in Bombay solves a baffling mystery)

- The Satapur Moonstone – Perveen Mistry #2 (A murder mystery set in colonial India highlights the princely states)

- The Bombay Prince – Perveen Mistry #3 (Murder in Bombay during the Indian independence movement)

For similar titles, see The best Indian detective novels.

You might also enjoy my posts:

- Good books about India, past and present

- Top 10 historical mysteries and thrillers

- Top 10 mystery and thriller series

- 30 outstanding detective series from around the world

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.