Few people today wonder what led to Japan’s unconditional surrender in World War II. The United States dropped atomic bombs on the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the Emperor caved. Job done. But of course the reality was far more complex. And the outcome was anything but certain.

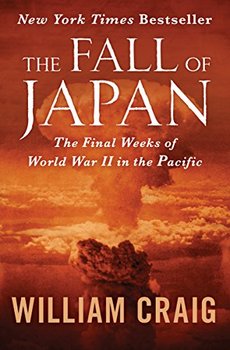

Twenty-two years after the war ended, American historian William Craig revealed how that decision came about. He dug into hidden documents and spoke with dozens of those who played pivotal roles at the time both in Japan and the US. Day-by-day, and often hour by hour, Craig reconstructed the events that unfolded in Tokyo as the Empire of Japan pondered the Allies’ inflexible demands. He focused on the fateful days between August 9, 1945, when Fat Man detonated over Nagasaki, and August 15, when Emperor Hirohito radioed a message to Switzerland accepting the Allied terms of surrender. The story Craig tells in The Fall of Japan is at once compelling, disturbing, and illuminating. This book is a stellar example of how history can shine a bright light underneath the surface myths and reveal the messy human reality of the past.

What really led up to Japan’s unconditional surrender

Emperor Hirohito (1901-89) was universally revered as a god by the Japanese people. Small wonder, then, that readers three-quarters of a century later might assume that all the man had to do was snap his fingers for the government to do his bidding. But that was far from the truth. Centuries earlier, during the shogunate of the Edo period (1600–1868), powerful warlords had sharply curtailed the emperor’s power. Although he was nominally restored to supreme power during the Meiji period (1868–1912), it was former samurai rather than the emperor who exercised real power.

Hirohito’s role was largely ceremonial

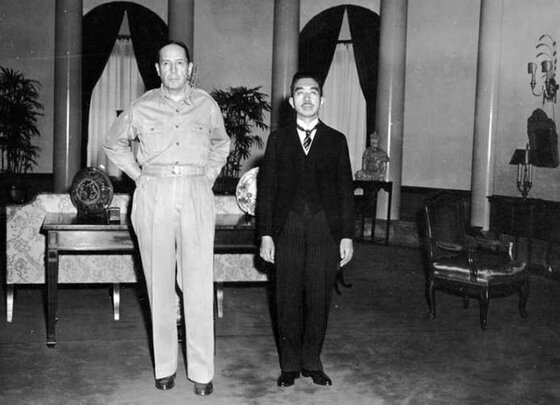

By the time Hirohito ascended to the throne in 1926, he was expected to observe the government and remain silent. Although controversy continues to surround his role in launching and prosecuting World War II, William Craig’s account makes clear that Hirohito quietly supported the military throughout the conflict. Only in the darkest days of August 1945 after nuclear weapons fell on Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the Soviet Union attacked the Japanese army in Manchuria did the emperor understand the end was truly at hand. But when he and members of his court and cabinet began to maneuver behind the scenes to move toward peace, the military pushed back. Japan’s unconditional surrender? Unthinkable!

Diplomats struggled to reach a peace agreement

As Craig notes, “While the new American President grappled with the problems of impending victory in the Pacific, and while the new Japanese Premier endeavored to construct some workable alternatives to absolute defeat, diplomatic and intelligence personnel of both nations were engaged in desperate, yet hopeful, schemes for ending the conflict quickly.” Yet their hopes foundered on the shoals of resistance by Japan’s military. And the military overshadowed the civilians in what was known as “the Big Six, Japan’s ‘inner cabinet,’ formally named the Supreme Council for the Direction of the War.” The war cabinet, in other words.

The military was fanatically committed to continuing the war

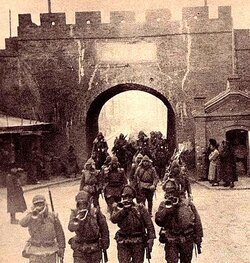

Ever since the renegade Kwantung Army attacked Chinese troops in the Mukden Incident in 1931, the Japanese military had been in the driver’s seat in Tokyo. For fourteen years, the army and navy dominated government policy, often in bitter conflict with each other. Of the two, the army was, if anything, more powerful. But the power dynamics were complex. Within both services, there were senior officers (most notably the late Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto) who recognized the suicidal folly of attacking the United States at Pearl Harbor.

Among the civilian leadership, too, opinion was divided. But as fighting raged across the Pacific, the dissenters remained quiet. A succession of Prime Ministers were forced to bow to the will of the Army, not least in fear of their lives if they contradicted the generals. And when the emperor consulted privately with members of his cabinet during the final months of the war, virtually all advised continuing to fight. Only one urged a negotiated settlement—even though unconditional surrender alone was on the table.

Only when all hope was lost did Hirohito speak out

Meanwhile, the US Army and Navy continued island-hopping ever closer to Japan’s home islands. By the time Okinawa fell in July 1945, it was clear to all but the most fanatic military officers that defeat was certain. But it was the fanatics who called the shots. Even after the two atomic bombs were dropped and the Soviet Union entered the war, the top leadership was sharply divided. The six-member war cabinet split down the middle, three against three. And the three who resisted either were “zealots, who still believed surrender a worse fate than death,” or feared retribution from younger officers. Eventually, Hirohito succumbed to pressure from members of his family and the peace faction in the cabinet and broke nearly a century of precedent to speak out for peace. Against all odds, Japan’s unconditional surrender became inevitable.

Hirohito informed the war cabinet that “I have studied the terms of the Allied reply and . . . I consider the reply to be acceptable. . . I cannot endure the thought of letting my people suffer any longer. . . At this point, the Emperor broke down” in tears, Craig reports. “Instead of rising to bow before the Emperor, most sat crying into their hands. Two men slid onto the floor. On elbows and knees, they cried uncontrollably.” But their devotion to the emperor prevailed.

The leadership, even the most fanatic militarists, acceded to his wish for a settlement—but the opposition in much of the officer corps remained steadfast. And fanatic junior officers—colonels, majors, captains—organized first one coup attempt, then another. Craig follows their activities almost hour by hour during those fraught six days from the sixth through the fifteenth of August. They came perilously close to assassinating the leaders of the peace faction, kidnapping Hirohito, and closing off all hope of dealing with the Allies.

“The war situation has developed not necessarily to Japan’s advantage”

Fanatic younger officers rampaging through the Imperial Palace failed to find the phonograph record of the emperor’s message to the people of Japan announcing the surrender. But it was a close call. And they did murder one of the most powerful members of the cabinet. Others in the leadership committed suicide, unable to face the reality of surrender or consumed by guilt over the loss. Finally, however, the Japanese people heard Emperor Hirohito’s high-pitched voice on the radio for the first time ever, declaring that the war was over.

Even the words Hirohito spoke reflected the deep divisions within the empire’s leadership—and his own ambivalence—as well as a cultural bias against directness. “The war situation has developed not necessarily to Japan’s advantage,” he announced, “while the general trends of the world have all turned against her interest” and thus “we have decided to effect a settlement of the present situation by resorting to an extraordinary measure.” Not only did Hirohito avoid using the word “surrender.” He also failed to acknowledge that by accepting the terms of the Potsdam Declaration, he was bowing to the inevitability of Japan’s unconditional surrender.

The Fall of Japan: The Final Weeks of World War II in the Pacific by William Craig (1967) 394 pages ★★★★★

Why the Japanese resisted unconditional surrender

Fear of being accountable for war crimes

For most Americans, the historical memory of atrocities in World War II centers on the Holocaust. But there was no lack of depravity in the Pacific region. In the Rape of Nanking (December 1937 to January 1938), between 50,000 and 300,000 Chinese died during those six weeks. Japanese commanders released their troops to wreak havoc in other Chinese cities as well. Tens of thousands more died. And Japanese soldiers inflicted the same sadism and brutality on the nearly 140,000 Allied military personnel they captured in the Pacific and Southeast Asia.

“By the time the war was over,” the British site Forces War Records reports, “a total of more than 30,000 POWs had died from starvation, diseases, and mistreatment both within and outside of the Japanese Mainland.” But none of this was unknown to either the military or the civilian leadership in Tokyo. And it was fear of being held to account for these crimes against humanity that played a leading role in Japan’s ferocious resistance to unconditional surrender even when all hope of victory was long gone.

Fear that the emperor would be deposed

But most accounts single out another concern that motivated the resistance to unconditional surrender among the Japanese leadership. To their minds, the imperial dynasty represented twenty-six hundred years of Japanese history. It was unthinkable that ending the war might bring that dynasty to an inglorious end. Even the most determined members of the peace faction in Japanese diplomatic circles emphasized the importance of preserving the emperor’s role in their overtures to the Allies through neutral Switzerland and Sweden.

But the root cause of the resistance was fanaticism

In the final analysis, however, it was fanaticism, pure and simple, that lay at the foundation of the resistance to surrendering. For the overwhelming majority of Japanese soldiers and sailors, and particularly so for the officers, abject devotion to the Bushidō warrior’s code caused them to reject reality. One of the primary values in the samurai life was loyalty and honor until death, never defeat, capture, and shame. For several years, ever since the tide of battle began to shift against them, thousands of Japanese soldiers at a time had ended their lives in suicidal charges against entrenched American forces. And the pace of these insanely self-destructive tactics increased in the final months of the conflict. Beginning in October 1944, a total of 3,800 kamikaze pilots willingly went to their deaths in suicidal attacks on American warships.

A rich source of insight and perspective

The Fall of Japan is an abundant source of insight and perspective on the final weeks of World War II in the Pacific. Although the author’s emphasis is on the struggle inside Tokyo during the critical six days that led up to Japan’s unconditional surrender, he relates many other aspects of the story in telling detail.

The fateful role of the American Air Force

Craig traces the emergence of the US Army Air Force as a central player in the war’s endgame. He details the firebombing strategy of General Curtis Lemay (1906-90) that killed far more Japanese than both the atomic bombs. Craig characterizes the firebombing of Tokyo as “the most ferocious holocaust ever visited on a civilized community.” The bombing there destroyed over 250,000 buildings, flattened almost sixteen square miles, and killed more than 100,000. Later, he follows the development of the plan to drop the atom bomb, dogging the footsteps of the crews of the B-29s through weeks of training and then on their fateful runs over Hiroshima and Nagasaki. His shattering accounts of the consequences for the people of those two doomed cities call to mind John Hersey’s Pulitzer-Prize-winning reporting in his 1946 book, Hiroshima.

Continuing resistance by Japanese soldiers

Even after the emperor’s message was broadcast, fanatic soldiers and sailors continued to act as though the war had not ended. Some rounded up captured B-29 pilots and summarily executed them. Others murdered their own colleagues who refused to join in continuing efforts to undermine the surrender. “Both in Japan and on the fringes of the Empire,” Craig reports, “trouble continued to plague the attempts at orderly surrender.” American soldiers pressed into the OSS to advance the American occupation of Japanese POW camps found themselves taken prisoner by camp commandants who doubted the authenticity of reports about the surrender. And the American soldiers who were first sent to Japan landed in fear of their lives. The Japanese officers sent to welcome them were fearful, too, that some deranged soldier might open up on them with a semi-automatic weapon.

About the author

Historian and novelist William Craig (1929-97) wrote two espionage thrillers as well as two widely respected nonfiction works about World War II. As his bio at the back reveals, “he interrupted his career as an advertising salesman to appear on the quiz show Tic-Tac-Dough in 1958. With his $42,000 in winnings—a record-breaking amount at the time—Craig enrolled at Columbia University and earned both an undergraduate and a master’s degree in history.” The Fall of Japan was the first product of his education.

For additional reading

This book is one of the best Books about World War II in the Pacific.

For a lucid and detailed account of the behind-the-scenes negotiations between Japan and the USA, see Unconditional: The Japanese Surrender in World War II by Marc Gallicchio (The unconditional Japanese surrender in WWII). And for an intriguing alternate history, see 1945 by Robert Conroy (What if Japan hadn’t surrendered?).

You might also be interested in:

- 10 top nonfiction books about World War II (plus many runners-up)

- The 10 best novels about World War II (with 30+ runners-up)

- 7 common misconceptions about World War II

- The 10 most consequential events of World War II

- Top 20 popular books for understanding American history

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, plus a guide to this whole site, on the Home Page.