Estimated reading time: 7 minutes

A teaser on the cover of the edition I read promises a tale of “a priceless manuscript, a missing scholar, and a trail of riddles.” And so it is. The ciphers, codes, and wordplay in the second entry in Vaseem Khan’s Malabar House series call to mind Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code and a smattering of mysteries based on ciphers and codes such as Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose. But The Dying Day is much more than that. It’s nothing less than a snapshot of modern India in its formative years as it struggled to forge a new identity just three years after it gained its independence.

Two baffling mysteries

If you’ve read Midnight at Malabar House, the first book in this series, you’ll know that Inspector Persis Wadia is the first female detective in the Indian Police Service (IPS). Having joined shortly after independence, she was assigned to the Bombay Constabulary’s dumping ground for misfits and political undesirables. That’s Malabar House, considered a standing joke in the IPS. Under the command of Roshan Seth, who has fallen out of favor with his superiors, Persis takes on politically sensitive cases that other commanders shun.

So it’s natural that when a baffling mystery turns up at the Asiatic Society Library, Seth calls her in. A priceless manuscript has gone missing. And so has the renowned English scholar who was studying it. But no sooner has Persis begun looking into the case than Seth assigns her to another as well. A young white woman’s mutilated body turns up on the railroad tracks. And Seth insists she supervise the detective who is the lead on the case. These two baffling mysteries will bedevil her for weeks—and of course it will eventually turn out that the two cases are linked in an entirely unexpected way.

The Dying Day (Malabar House #2) by Vaseem Khan (2021) 352 pages ★★★★☆

Tantalizing literary clues

From the imperious English librarian at the Asiatic Society, Persis learns that the missing manuscript is “our most priceless artifact . . . a copy of Dante Alighieri’s La Divina Commedia—The Divine Comedy—one of the two oldest copies in the world.” And John Healy, one of the world’s leading scholars on Dante, has disappeared. But he has left behind a series of tantalizing literary clues in Latin, Greek, and English poetry that will take Persis on a long, frustrating search across Bombay for what she hopes is the manuscript. And along the way she will encounter several other people—an Italian scholar, an English journalist, and an American representing the Smithsonian Institution—who have their own reasons to want to find the manuscript. And none of them is easy with the truth.

Meanwhile, Persis must also “supervise” George Fernandes, the detective who is leading the investigation into the death of the young woman on the railroad tracks. But because she loathes Fernandes—for good reason—she interprets Seth’s assignment to mean that it’s she who is actually in charge. The two detectives will clash repeatedly as they move along parallel paths toward a shocking resolution of the case.

A snapshot of India shortly after independence

In 1950, when The Dying Day is set, India was just coming into its own. Three years after gaining its independence, the country’s new, democratic Constitution was just then going into force. It was largely the work of the brilliant government official Dr. Bhimrao Ambedkar and reflected the discrimination he’d suffered all his life as an “untouchable” (Dalit). The new constitution outlawed the practice of untouchability and provided for an Indian version of affirmative action through quotas favoring those on the bottom rungs of the caste ladder. But no constitution, and no law, could come to grips with the religious differences that had torn the nation apart in Partition and would poison Indian society to this very day.

Those differences and the tensions they cause are fully in evidence in The Dying Day. Persis is a Parsi (Parsee), a member of a tiny but influential minority with its roots in medieval Iran. Hindus, Muslims, and Christians surround her wherever she goes, sometimes clashing with one another and throwing up roadblocks in her path.

The Dying Day is studded with historical vignettes that together paint a picture of India’s tumultuous past. Queen Victoria’s announcement declaring the country a colony of the crown, dispossessing the corrupt British East India Company. The Quit India campaign led by Mohandas Gandhi. World War II, when two million Indians served the British while thousands of others allied with the Japanese in a breakaway force. The unspeakable terrors of Partition, when millions lost their lives in the ill-considered birth of Pakistan. It’s all there, and it fits in context.

India’s real first female police officer

No surprise here: Persis Wadia was not the first lady detective in India. In fact, a social activist named Kiran Bedi (1949-) was the first woman to join the Indian Police Service (IPS) as an officer. And that was in 1972, nearly a generation after Vaseem Khan has the young Parsi woman join the force. Bedi was a social reformer who was “instrumental in introducing prison reform in India,” according to the Encyclopedia Britannica. She later gained both a law degree and a PhD in social science and became the first woman to serve as an advisor to the United Nations Police.

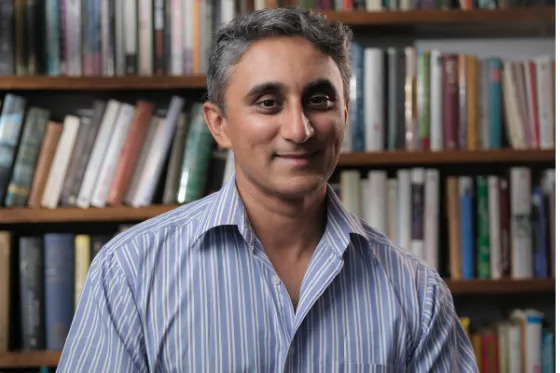

About the author

On his author website, Vaseem Khan introduces himself as follows: “Vaseem Khan is the author of two award-winning crime series set in India, the Baby Ganesh Agency series set in modern Mumbai, and the Malabar House historical crime novels set in 1950s Bombay. . . When he isn’t writing, he works at the Department of Security and Crime Science at University College London. Vaseem was born in England, but spent a decade working in India.”

Khan was born in London in 1973 and possesses a degree from the London School of Economics.

For related reading

I’ve also reviewed three other books in the Malabar House series:

- Midnight at Malabar House (A compelling murder mystery set in India after Partition)

- The Lost Man of Bombay (A baffling murder mystery in post-Independence India)

- Death of a Lesser God (Murder in the shadow of Partition)

Be sure to check out The best Indian detective novels and Good books about India, past and present.

I’ve reviewed three books by Amy Stewart about Constance Kopp, the first woman deputy sheriff in the United States:

- Girl Waits With Gun (She was the country’s first female deputy sheriff)

- Lady Cop Makes Trouble (A real lady cop a century ago in an excellent fact-based crime novel)

- Miss Kopp’s Midnight Confessions (The lady cop who fascinated America a century ago)

You might also enjoy my posts:

- Top 10 mystery and thriller series

- 20 excellent standalone mysteries and thrillers

- 30 outstanding detective series from around the world

- Top 20 suspenseful detective novels

- Top 10 historical mysteries and thrillers

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.