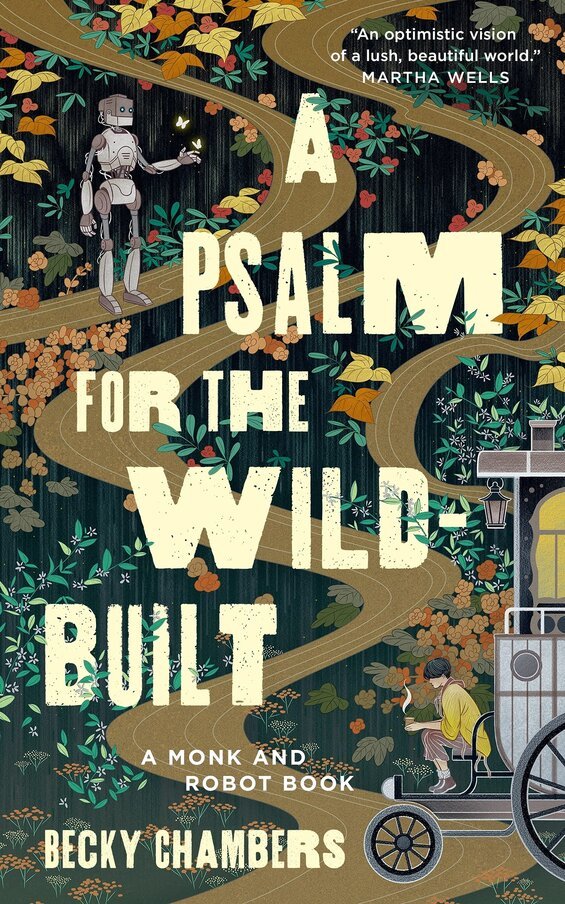

Becky Chambers has made a name for herself among the newer crop of science fiction authors with her outstanding Wayfarers series, which won the Hugo Award for Best Series. The four books in that inaugural series introduced readers to a delightful future. Beginning with The Long Way to a Small, Angry Planet, we encountered human colonists throughout the galaxy who constituted just one of many sentient species, and not a particularly special one at that. Now, in A Psalm for the Wild-Built, Chambers takes us once again into a distant future. This charming little novel debuts a monk named Sibling Dex and Splendid Speckled Mosscap, a robot. The two are the protagonists of a new science fiction series, the Monk and Robot books. And these stories seem bound for a slew of new awards.

Monk and Robot star in this enchanting story

First, a word about those names. The monk, Sibling Dex, is of indeterminate gender. Hence, “Sibling” rather than “Brother” or “Sister.” And the robot gained its name upon first awakening and seeing before its eyes a stand of Splendid Speckled Mosscap mushrooms. And thus we know we’re now in a fanciful and unfamiliar future.

A Psalm for the Wild-Built (Monk & Robot #1) by Becky Chambers (2021) 160 pages ★★★★☆

A new science fiction series spotlights balance with nature

The human race had arrived uncounted centuries ago. Colonists now lived on a moon called Panga orbiting a gas giant in a faraway star system. An industrial civilization (“the Factory Age”) emerged, with robots doing all the work. Then, 200 years ago, to the humans’ surprise, robots gained sentience (“the Awakening”). As one, they abandoned civilization for the wilderness on the half of Panga that had been reserved for non-human species. Once again humans were forced to learn how to fend for themselves. And they have managed to do so, building a new, agrarian society to feed the people of Panga’s only City and its many outlying towns and villages.

Yet this is not a civilization like that of the Factory Age. “Decay was a built-in function of the City’s towers, crafted from translucent casein and mycellium masonry. Those walls would, in time, begin to decompose, at which point they’d either be repaired by materials grown for that express purpose, or, if the building was no longer in use, be reabsorbed into the landscape that had hosted it for a time.”

This is the world in which Sibling Dex lives a contented life as a monk—until, all of a sudden, they are no longer content. In search of a place where they might hear the music of the crickets, they leave the monastery in the City and venture out onto the road. Now employed as a tea monk, they ride a bicycle-powered wagon from village to village, dispensing tea and a sympathetic ear (“listen to people, give tea”). In time, Sibling Dex becomes “the best tea monk in Panga.”

A journey to the fringes of the wilderness

Eventually, though, even life as a tea monk fails to satisfy. Sibling Dex sets out on a road to the fringes of the wilderness to visit an abandoned monastic refuge to ponder life’s mysteries. And on the way, they encounter Splendid Speckled Mosscap, Mosscap for short—”a seven-foot-tall, metal-plated, boxy-headed robot.” It’s the first encounter in 200 years between human and robot and a jarring experience for both. Thus begin the adventures of Monk and Robot in the inaugural effort of this new science fiction series.

Nature is paramount in the new faith

The allusion to religion in the title A Psalm for the Wild-Built is no accident. Chambers’ theme is, in fact, spiritual. She has created a pantheon of six gods, three Parent Gods and three Child Gods. Sibling Dex is a devotee of the Child God Allalae, God of Small Comforts. In their faith, nature is paramount, and the environment dominates much of what passes in conversation between Sibling Dex and Mosscap. For example, as Mosscap observes, “The paradox is that the ecosystem as a whole needs its participants to act with restraint in order to avoid collapse, but the participants themselves have no inbuilt mechanism to encourage such behavior.”

An engaging essay on ecology

In the final analysis, this new science fiction series is an essay on ecology, or at least the first book is that. “It is difficult for anyone born and raised in human infrastructure,” Chambers writes, “to truly internalize the fact that your view of the natural world is backward. Even if you fully know that you live in a natural world that existed before you and will continue long after, even if you know that the wilderness is the default state of things, and that nature is not something that only happens in carefully curated enclaves between towns, something that pops up in empty spaces if you ignore them for awhile, even if you spend your whole life believing yourself to be deeply in touch with the ebb and flow, the cycle, the ecosystem as it actually is, you will still have trouble picturing an untouched world. You will still struggle to understand that human constructs are carved out and overlaid, that these are the places that are the in-between, not the other way around.” Amen to that.

As Mosscap remarks to Dex, “You keep asking why your work is not enough, and I don’t know how to answer that, because it is enough to exist in the world and marvel at it. You don’t need to justify that, or earn it. You are allowed just to live.”

For more reading

I’ve reviewed all five of Becky Chambers’ earlier novels:

- The Long Way to a Small, Angry Planet (Wayfarers #1) ★★★★★ – A delightful modern space opera that’s all about character development

- A Closed and Common Orbit (Wayfarers #2) ★★★★☆– Lovable characters in this off-beat space opera

- Record of a Spaceborn Few (Wayfarers #3) ★★★★★ – A brilliant invented universe in an unusually good new science fiction novel

- The Galaxy, and the Ground Within (Wayfarers #4 of 4) ★★★★☆ – The last of the Wayfarers series from Becky Chambers

- To Be Taught, If Fortunate ★★★★☆ An excellent hard science fiction novella from Becky Chambers

For more good reading, check out:

- The ultimate guide to the all-time best science fiction novels

- Great sci-fi novels reviewed: my top 10 (plus 100 runners-up)

- The five best First Contact novels

- Seven new science fiction authors worth reading

- The top 10 dystopian novels reviewed here

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, plus a guide to this whole site, on the Home Page.