Estimated reading time: 8 minutes

History speaks of two insurrections against Nazi rule that erupted in Warsaw during World War II. Americans sometimes confuse the two. Chronologically, the second of these events was the Warsaw Uprising led by Polish partisans that unfolded from August 1 to October 2, 1944. The event is remembered because a huge Soviet army had advanced to within the city limits but declined to intervene on behalf of the Poles, who were systematically slaughtered by the Germans.

The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising

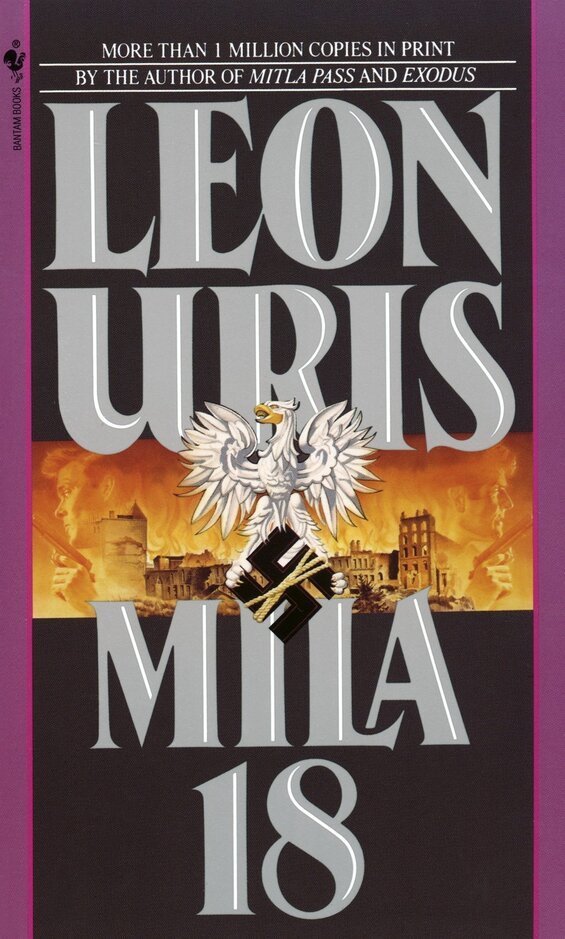

A year and a half earlier—from April 19 to May 16, 1943, the Jewish Combat Organization, or ZOB, battled SS troops and their local collaborators who had moved in to the Warsaw Ghetto to slaughter the estimated 70,000 to 80,000 Jews remaining there. (Some 265,000 others from the ghetto’s population when the Germans established it in October 1940 had earlier been deported to the Treblinka extermination camp.) Popular novelist Leon Uris memorialized the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising in his explosive bestselling novel, Mila 18. His story, published sixty years ago when World War II was less than two decades in the past, examines the experience of the 400,000 Jews who lived in the city as the war arrived.

Two interlocking families at the center of the tale

To dramatize the events that unfolded from September 1939, when the Nazis invaded Poland, to April 1943, Uris follows the misfortunes of two Jewish families and their friends as well as the German officials and military officers who engineered the massacre of the Warsaw Ghetto.

Mila 18 by Leon Uris (1961) 539 pages ★★★★☆

Paul Bronski

Dr. Paul Bronski is an eminent physician. He serves in the prestigious post of Dean of the School of Medicine at Warsaw University until the Nazis force him and all other Jewish academics out of their jobs. He does not identify as Jewish. However, his wife, Deborah, is a believer. She and her brother, Andrei Androfski, are the children of pious Orthodox Jewish parents. And Andrei is militant in his Judaism, a leader in the Zionist movement that had gained a foothold in Poland over the preceding half-century.

Andrei Androfski

As the novel opens, Andrei serves as a lieutenant in a storied Ulany regiment, a crack cavalry unit of the Polish Army. After distinguishing himself in the nation’s defense against the invasion, he is elevated to captain. He’s a big man, a ferocious fighter, and a survivor, and we witness him taking a leading role in the Jewish underground movement that launches the defense of the ghetto. However, his Judaism notwithstanding, he falls in love with a Polish woman, Gabriela Rak, who herself later plays a significant role in the underground. “If a shiksa was good enough for Moses,” he tells a friend, “a shiksa is good enough for Androfski.”

Christopher de Monti

Journalist Christopher de Monti is involved in another forbidden romance, his with Deborah Bronski. The two are passionately in love, but Deborah will not leave Paul behind or upset her two children. Chris is the man in Poland for the Swiss News Service. He carries an Italian passport, but his mother is American and he identifies more closely with the USA than with Italy. He is at loggerheads with his father, a wealthy Italian aristocrat in bed with Mussolini’s fascists. Together with a Polish Jew, Ervin Rosenblum, Chris labors to evade Nazi obstructions and a smokescreen of propaganda to get the truth out to the world about events in Poland.

Alexander Brandel

Alexander Brandel is among Andrei’s friends but represents a great contrast to him. He is an intellectual. His journal of the events around him morphs into a collaborative effort involving dozens of others once they are forced into the ghetto and the Nazis’ intentions start to become clear. Alex’s son, Wolf Brandel, sixteen years old as the novel opens, falls in love with Rachel Bronski, and they manage to spend time together despite the strictures of family and the war. Wolf will become a central figure in the uprising.

Chief characters among the Germans

Dr. Franz Koenig

Franz Koenig had smarted for years, ever since the Jew Paul Bronski had risen to become Dean of the Medical School. When his chance comes, he exults in humiliating his former boss, even evicting the family from his palatial home and moving in himself. And when the Nazis move to exert close control over events in Warsaw, they find in Koenig a useful collaborator. He, in turn, becomes embroiled in black market operations and gains great wealth stolen from Jewish families. The Germans are content to let him act as he will because he serves as a useful adviser to the clueless Nazi officials placed in control over the city.

Rudolph Schreiker

Rudolph Schreiker is named Commissar of Warsaw once the Germans break through on their siege of the city. He is a remarkably stupid man, raised far above his abilities because of his ardent loyalty to the Führer. Koenig finds him easy to manipulate.

Horst von Epp

Dispatched from Berlin, where he developed much of the Nazi propaganda used so effectively by Joseph Goebbels, Horst von Epp is a literate and courtly man who has little sympathy for the Nazis he is forced to work with. His chief role in the story is as a brake on the impulsive and irrational actions of Oberführer (Colonel) Alfred Funk.

Alfred Funk

Alfred Funk is the communications link between Adolf Eichmann and Reinhard Heydrich in Berlin and the top Nazis in Poland. He carries orders to Warsaw from the German capital and the top officials in occupied Poland, who are located not in Warsaw but in Lublin and Kraków. Funk is the overall commander of German forces in Warsaw and bears overall responsibility for crushing the Warsaw Uprising.

Other Nazi officers, including Eichmann and Heydrich, appear off-stage in central roles as the Nazis’ “Final Solution” unfolds under their leadership.

A stirring account, but melodramatic

MIla 18 is a stirring account of human courage in the face of insurmountable odds. I’ve never seen anywhere else such a detailed picture of the events of March and April 1943, week by week and often day by day. Not in any novel of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising or any history book. The focus on the Bronski and Brandel families lends the tale an intimate touch. The writing, however, is never brilliant. And at times the story comes across as melodramatic.

On a personal note

In 1965, after I cut short my graduate school education at Columbia University, I spent the summer and early fall traveling in Eastern Europe, the Soviet Union, and Scandinavia, with short stops toward the end in Germany, France, and the UK. It was what used to be called the Grand Tour. (I financed the hideously expensive trip with money I’d made speculating on the stock and commodity markets while cutting classes at Columbia.) The trip was an eye-opener.

I began my trip through Eastern Europe in Poland, visiting Kraków, Auschwitz, and Warsaw. The experience was shattering. Of course, Auschwitz was by far the most troubling, as I could easily imagine that some of the bones and hanks of hair and eyeglasses I saw heaped up in displays there had once belonged to distant relatives of mine. But Warsaw, too, was a shock.

The siege of Warsaw in 1939, the two uprisings, and the devastating artillery bombardment by the Soviet army in 1945 left little standing in the “Paris of the East.” And when I visited the city twenty years after the war, broad vistas of rubble still met my eye. The USSR, more intent on looting what little of value had been left behind by the Nazis, had done little to rebuild beyond erecting a few ugly high-rise apartment buildings. It was a sobering reminder of how important government can be.

About the author

Leon Uris was born in Baltimore, Maryland, the son of Jewish immigrants. His father was Polish, his mother first-generation Russian-American. He enlisted with the Marines and served in World War II in the Pacific, fighting as a radioman in combat on Guadalcanal and Tarawa from 1942 through 1944. Uris’s fame rests largely on his 1958 novel Exodus, but he wrote many other bestselling books over nearly half a century. His career had begun in 1953 with the publication of another widely read title, Battle Cry.

For related reading

For another novelist’s take on the same theme, see The Book of Aron by Jim Shephard (A brilliant novel of the Warsaw Ghetto). You might also check out We Must Not Think of Ourselves by Lauren Grodstein (The drama before the Warsaw ghetto uprising) and The War Girls by V. S. Alexander (Life in wartime Warsaw before the Ghetto Uprising), although the book is not as well written.

You might also enjoy:

- 10 top nonfiction books about World War II

- The 10 best novels about World War II (with 40 runners-up)

- 15 good books about the Holocaust, including both fiction and nonfiction

- 7 common misconceptions about World War II

- The 10 most consequential events of World War II

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, plus a guide to this whole site, on the Home Page.