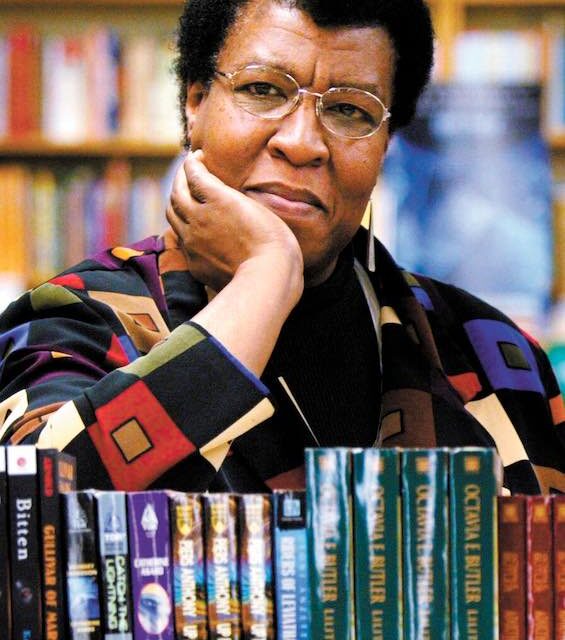

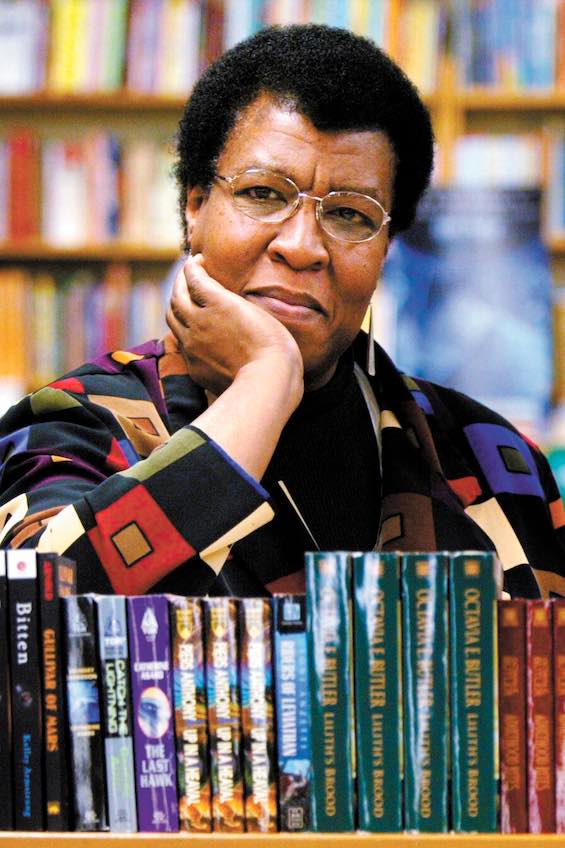

Octavia Butler was the author of three cycles of science fiction novels—two Parable books, the Xenogenesis trilogy, and five books in the Patternmaster series—as well as two standalone novels. She is also credited with seven graphic novels (including Black Panther) produced in collaboration with Nnedi Okorafor and two short story collections. Butler’s first novel, Patternmaster, appeared in 1976, her last, the standalone novel Fledgling, in 2005.

Butler was born in the racially integrated community of Pasadena, California, in 1947, and began writing science fiction as a teenager. She attended community college during the Black Power movement. After achieving success when her first stories were published in the late 1970s, she turned to writing full-time. She won widespread praise for her work, including multiple Hugo, Nebula, and Locus awards. And in 1995, she became the first science fiction writer to receive a MacArthur Foundation “genius grant.”

Butler died of a stroke in Washington State in 2006 at the age of 58.

Long-overdue recognition

Although Butler’s science fiction was celebrated during her lifetime—after all, she won numerous awards—her name doesn’t often appear on lists of the greatest science fiction authors. She deserves to be included. And the New York Times recognized that need with a cover story in its Sunday Arts & Leisure section on November 27, 2022. In a two-page article entitled “The Future Foretold,” Lynell George wrote:

“As a child, Octavia Butler dreamed bold in a world that made her feel little. Then she began to write about her visions of worlds that could be different. On the eve of a major revival of her works” marking the seventy-fifth anniversary of her birth, “this is the story of how she came to see a future that is now our present. . . Her vision about the climate crisis, political and social upheaval, and the brutality and consequences of power hierarchies seems both sobering and prescient.”

George also notes that “Five adaptations of her fiction are currently in various stages of film and television development, by producers who include J. J. Abrams, Issa Rae and Ava DuVernay.”

George’s print article is just one aspect of a major multimedia project mounted by the Times. The online version, “The Visions of Octavia Butler,” is lavishly illustrated and interactive. “It examines key locations and moments from Ms. Butler’s life . . . and how they shaped her writing.”

Below you’ll find excerpts from my reviews of the five best-known of Octavia Butler’s novels. The links lead to the full text.

The Earthseed duology

The Parable of the Sower – Parable #1 of 2 (1993) 368 pages ★★★★★—A superb dystopian novel by Octavia E. Butler)

Welcome to one of the most acclaimed dystopian novels of recent times. Fifteen-year-old Lauren Olamina is the daughter of a Baptist minister and the eldest of his five children. Both Reverend Olamina and his second wife, Lauren’s stepmother, are African-American, and both hold PhDs. Lauren’s father teaches at a local college, her stepmother at the neighborhood elementary school.

The year is 2024—the novel was published three decades earlier—and American civilization is in tatters. The drug epidemic, global warming, and the cost of endless foreign intervention have taken their toll. Government is breaking down. The police now demand “fees” for their services and frequently fail to provide them, anyway—or arrest the victim. A tiny number of immensely wealthy families live behind walls on estates patrolled by private armies. “There are at least two guns in every household.” >>Read more

The Parable of the Talents – Parable #2 of 2 (1998) 448 pages ★★★★★—Classic science fiction with a timely message

Read the two-book Parable series or the five-volume Xenogenesis cycle, and you’ll understand why Octavia Butler won a MacArthur Foundation genius grant as well as multiple Hugo and Nebula awards. The Parable of the Talents, the second of the two Parable novels, may be the best of all her long fiction. Today, it reads as though she might have written it yesterday. Yet if any book published in the last three decades or so could be referred to as classic science fiction, this is it.

The Parable cycle tells the tale of Lauren Oya Olamina Bankole and the Earthseed belief system she creates in the midst of a violent and chaotic American future. In the midst of our collapsing civilization—a period known as “the Apocalypse” or “the Pox”—a demagogue named Jarrett is elected President. His followers, reminiscent of the Ku Klux Klan, rampage throughout the country, imposing their racist and intolerant “Christian America” faith through wholesale murder and reeducation camps. In “Earthseed: The Books of the Living,” Lauren reflects after a fashion so many Americans might have been thinking in recent years:

Choose your leaders with wisdom and forethought. To be led by a coward is to be controlled by all that the coward fears. To be led by a fool is to be led by the opportunists who control the fool. To be led by a thief is to offer up your most precious treasures to be stolen. To be led by a liar is to ask to be told lies. To be led by a tyrant is to sell yourself and those you love into slavery. >>Read more

The Lilith’s Brood trilogy

Dawn – Xenogenesis Trilogy #1 (1987) 310 pages ★★★★★—A science fiction novel that illuminates the human condition

At its best, science fiction illuminates the human condition. It does so by exploring our emotions and our behavior in a context that violates our sense of reality and challenges us to look more deeply into ourselves. The late Octavia E. Butler reached this peak of insight more often than most in her field. Dawn, the first book in the Xenogenesis Trilogy, is a brilliant example.

A young woman named Lilith awakens from suspended animation into one of the most convincingly alien worlds in the genre. She is confined within a small, all-white room with neither windows nor a door. The light is bright and constant. At intervals, bowls of food extrude from one of the walls. At length, a disembodied voice speaks to her in English, growing silent when she asks a question it declines to answer. When the speaker finally is revealed, Lilith is repulsed. The creature that has materialized in the corner of the room is indescribably ugly to her eyes.

This how Dawn opens, and if anything the story grows stranger by the page. When Lilith finally begins to encounter other human beings, the sparks quickly begin to fly. After a slow start, the action builds to a crescendo, setting the scene for its sequels in the Xenogenesis Trilogy. This is First Contact of a high order. >>Read more

Adulthood Rites – Xenogenesis Trilogy #2 (1988) 336 pages ★★★★☆—They have extraordinary powers, but you’d never call them superheroes

In this worthy sequel to Dawn, the focus shifts from Lilith Ayapo to her son Akin (“AH-keen”). The infant is a “construct,” the product of a Human mother and father, and the three Ooankali individuals (male, female, and a third gender) who are necessary to bring Akin into the world. As a construct, Akin possesses many of the extraordinary powers of the alien species even though he looks very much like a Human: he begins speaking in complete sentences as an infant, he remembers everything he’s ever seen or done (including his experiences in Lilith’s womb), and he is capable of killing Humans with the sting of his tongue.

Science fiction? Maybe. But there’s little science in this engrossing trio of novels. Most would call this fantasy.

However it might be characterized, this is, indeed, a very strange tale. The conceit on which it is based is that humanity has virtually destroyed itself and devastated Planet Earth in the process, leaving tiny pockets of survivors scattered across the globe. The Ooankali have descended on Earth in what they consider a mission of mercy, intent on allowing the human race to go extinct because of our self-destructive behavior. >>Read more

Imago – Xenogenesis Trilogy #3 (1989) 230 pages ★★★☆☆—A science fiction novel that’s all about sex

This novel, the concluding entry in Octavia Butler‘s Xenogenesis Trilogy (also packaged as Lilith’s Brood), follows the misadventures of one of Lilith’s innumerable offspring. It—because you can’t call it he, she, or he/she, since it’s a third, distinctive gender—is named Jodahs. It’s a sibling of Akin, who was the protagonist in Adulthood Rites, the preceding novel in the trilogy. Jodahs is the product of a Human female (Lilith), a Human male (Lilith’s long-dead lover Joseph), and three Oankali, a male, a female, and an ooloi. (Don’t ask. Just know that the ooloi is the key to making the whole thing work.)

Confused? I understand. I was, too. Unfortunately, Imago is full of explanations like this—tediously so. After the startling strangeness of Dawn, the first novel in the trilogy, and the competent follow-up in Adulthood Rites, Imago is a disappointment. It’s practically all about sex. I yearned for more action and less talk about procreation. The novel is a sad conclusion for an otherwise outstanding trilogy. >>Read more

For more reading

For more good reading, check out:

- These novels won both Hugo and Nebula Awards

- The ultimate guide to the all-time best science fiction novels

- 10 top science fiction novels

- The top 10 dystopian novels reviewed here

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, plus a guide to this whole site, on the Home Page.