Estimated reading time: 8 minutes

Historians debate whether Britain’s Special Operations Executive (SOE) and the American Office of Strategic Services (OSS) had a material effect on the outcome of World War II. After all, they operated on the margins, behind enemy lines, never capable of mounting strategically significant missions. But later testimony from military leaders in the war effort insisted they’d made a difference. And whatever their strategic impact might have been, their activities—especially the often colorful antics of the OSS—make for great reading. Which you’re likely to conclude from the latest addition to the abundant literature about Wild Bill Donovan and his charges in the OSS, The Dirty Tricks Department. In the book, historian John Lisle peers into the record of the secret warfare waged by the OSS, revealing some of the agency’s most flamboyant activities.

Calling for Professor Moriarty

When the OSS was launched in July 1942 after a year under another name, the new agency seemed ready for war. Specialized branches sprouted in every direction. It was equipped to organize foreign resistance groups. Broadcast anti-Axis radio programs in Europe. Send spies abroad to supply information to the military. Spread misinformation to lower enemy morale. And “evaluate the flood of information that came pouring in from OSS agents and contacts abroad.”

Roosevelt and the Pentagon would soon move some of these branches to other agencies. But even what Wild Bill Donovan had at the outset wasn’t enough. “Donovan needed another branch, the most underhanded of them all, to destroy the enemy. He needed a branch that could equip an undercover agent with a fighting knife to slit a guard’s throat, an incendiary device to set a building on fire, a camouflaged explosive to blow apart a locomotive’s boiler, or a cyanide pill [for agents] to kill themselves with before being captured alive. He needed a branch that could develop and deploy all of the dirty tricks that were needed to win the greatest war in history. And he needed a scientist, a ‘Professor Moriarty,’ in his words, to oversee it.” Enter Dr. Stanley P. Lovell.

The Dirty Tricks Department: Stanley Lovell, the OSS, and the Masterminds of World War II Secret Warfare by John Lisle (2023) 384 pages ★★★★☆

A cornucopia of deadly devices

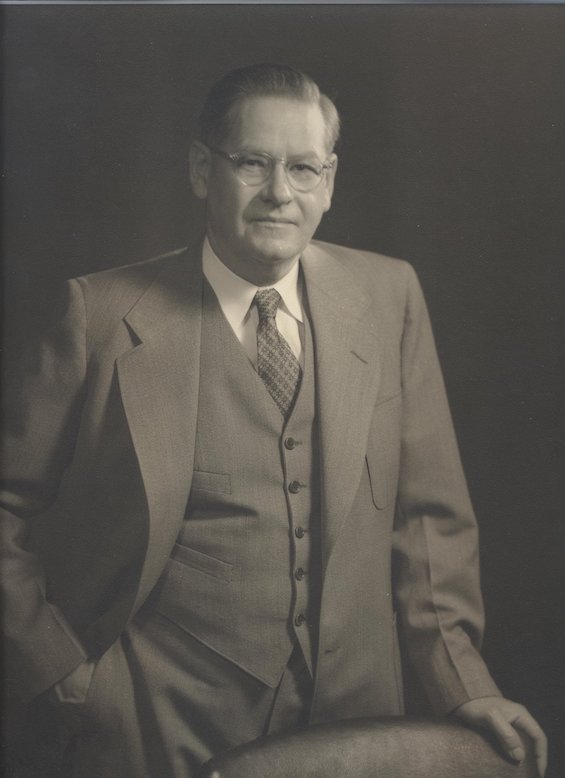

Stanley Lovell was an industrial chemist with a bachelor’s degree in the field from Cornell. (He began but never finished work on a graduate degree. The “Dr” before his name came later from an honorary degree.) Lisle describes Lovell’s first encounter with the already famous head of the OSS. “‘I’m Colonel Donovan,’ the man said. ‘You know your Sherlock Holmes, of course. Professor Moriarty is the man I want for my staff here at O.S.S. I think you’re it. . . . I need every subtle device and every underhanded trick to use against the Germans and the Japanese.’ He paused, then gave Lovell his first order: ‘You have to invent all of them, Lovell, because you’re going to be my man.'” And invent them he did—although in reality the large and growing staff he recruited for the OSS’s new R&D Branch did the inventing.

Under Lovell’s direction, some of the nation’s brightest, and some of the nuttiest, scientists went to work. During the last two years of the war, the R&D staff designed and built a wide array of deadly devices. Lisle singles out the “time pencil,” which exploded after a timed delay “to ignite a wallet-sized reservoir of napalm,” and “the limpet mine, a small box of explosives that attached to the hull of a metal ship.” Oh, and the “‘Hedy,” a “device that simulated the screech of a falling bomb.” That one caused havoc when Lovell demonstrated it to the Joint Chiefs of Staff without advance warning. (They never invited him back.)

But these devices were the ones that worked. Many did not. There were explosive weapons that killed more Americans than Germans. “Bat Bombs” that attached explosives . . . yes, to bats . . . but failed to reach their targets. And other cockamamie schemes that caused Pentagon officials to raise their eyebrows—or laugh uproariously.

Even more deadly devices

A journalistic website that covers military culture, foreign policy and defense news describes some of the other output. Among the products were “silenced pistols and submachine guns and explosives disguised as lumps of coal (‘Black Joe’) or mule turds and even [explosive] Chinese flour, which the troops called ‘Aunt Jemima.’ The flour could even be baked and eaten in an emergency. . . Other ingenious gadgets included buttons with compasses inside to aid in escape and evasion, playing cards that concealed maps, a 16mm Kodak camera in the shape of a matchbox as well as German and Japanese identity cards, rations cards, passes and counterfeit currency.” Lovell and his minions would have put James Bond’s “Q” to shame.

But Stanley Lovell and his staff didn’t limit themselves to creating physical devices. The R&D Branch also included divisions dedicated to such tasks as creating disguises for spies, developing the “legends” that shrouded their past, producing counterfeit stamps and documentation, designing camouflage clothing, introducing “stench warfare,” and training agents in vicious hand-to-hand fighting techniques. R&D Branch was a full-service organization. More fatefully, R&D brought the OSS into the realm of biological and chemical warfare as well. And Lovell began extensive research on scopolamine, a supposed “truth drug.”

Close collaboration with the British

As Lisle emphasizes, “the R&D Branch shared many of its devices with the British SOE, but the exchange went both ways. . . One item that the SOE developed was an itching powder made from the needle-like hairs on the seedpods of the mucuna plant. On one occasion, a worker in a French clothing factory sprinkled liberal quantities of the powder on vests that were destined for the German Navy. Soon afterward, a German U-boat returned to port when its crew complained of a mysterious epidemic that had broken out among them. Another time, the itching powder was put inside German condoms. Local hospitals soon noted an uptick in reports of painful irritation during sex. And as an added bonus, the condoms had been sold at a handsome profit.”

A cast of endlessly entertaining characters

The eminent chemist Dr. Stanley Lovell emerges from this account as central to the story. But The Dirty Tricks Department is not truly biographical, as the book’s subtitle might suggest. Lovell is merely first among many men in the OSS (and the SOE) whose decisions helped guide the course of his agency’s efforts in the field. In fact, much of the work Lovell set in motion proved to be impractical. However, it was always arresting and makes for great copy. Other key OSS personnel, including Wild Bill Donovan himself as well as Allen Dulles and Moe Berg, outshine Lovell more often than not. In fact, Donovan’s astonishing story alone is worth the price of the book. I learned a great deal about the man from LIsle’s account even after I’d read Douglas Waller’s excellent biography.

Stanley Lovell’s legacy

“Stanley Lovell’s most consequential legacy,” Lisle writes, “wasn’t the deadly weapons, cunning schemes, forged documents, or secret disguises that the R&D Branch created. It was the inspiration that his truth drug experiments gave to a new generation of CIA scientists who would conduct one of the most infamous programs in American history.” MK-Ultra, the agency’s clandestine experiments that administered LSD and other psychoactive drugs to unwitting subjects in the 1950s and early 1960s. A program that famously led to the death of a government biological warfare specialist named Frank Olson in 1953.

About the author

According to his author website, “John Lisle is a historian from Azle, Texas. He earned a Ph.D. in history from the University of Texas, where he currently teaches courses on the history of science. John has received research and writing awards from the National Academy of Sciences, the American Institute of Physics, the California Institute of Technology, the National Endowment for the Humanities, and others. His writing has appeared in Scientific American, Smithsonian Magazine, Skeptic, the Journal of Intelligence History, and Physics in Perspective.

“John lives in Austin, Texas, with his wife.” The Dirty Tricks Department is his first book.

For related reading

This book is a runner-up to the 10 top WWII books about espionage.

Check out these revealing nonfiction books:

- Wild Bill Donovan: The Spymaster Who Created the OSS and Modern American Espionage by Douglas Waller (The remarkable spymaster who launched the US into espionage)

- Need to Know: World War II and the Rise of American Intelligence by Nicholas Reynolds (The rise of American intelligence in World War II)

- The Catcher Was a Spy: The Mysterious Life of Moe Berg by Nicholas Dawidoff (An absorbing biography of Moe Berg, baseball player and WWII spy)

And there’s a superb novel about what Lisle terms Stanley Lovell’s “most consequential legacy:” The Coldest Warrior by Paul Vidich (Project MK-Ultra and the scientist who fell to his death).

You might also enjoy:

- 10 top nonfiction books about World War II

- 7 common misconceptions about World War II

- The 10 most consequential events of World War II

- Top 20 popular books for understanding American history

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.