In the years following World War II, the emerging Cold War took on global dimensions. Then Britain, still clung on to its far-flung empire,. And the conflict with the Soviet Union played itself out not just at home and in Eastern Europe but throughout its possessions in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. There, the often-outclassed and outnumbered officers of MI6 and MI5 faced off against the massive forces of the NKVD and the GRU. And one of Britain’s most accomplished novelists, Graham Greene, later spotlighted their competition in South Africa in the short novel, The Human Factor. Set largely in London in the 1960s, the novel explores the human dimensions of the hunt for a Soviet mole in MI6’s Africa section.

Amateurish and morally compromised old boys

Greene was himself a veteran of MI6. For three years during World War II, he served in Sierra Leone as an officer of the spy agency. Clearly, the experience troubled him. His portrayal of MI6 in The Human Factor and other novels is unflattering. Top officials in the agency are morally compromised, to put the most charitable spin on how he depicts their actions.

At the same time, he depicts the Eton-and-Oxbridge old boys’ network then running the agency as consisting of entitled, self-important, upper-class men—they’re all men—who take refuge in their clubs, far from the harsh realities of daily life in post-war England. And this picture comports with historians’ assessment of British intelligence in that era. The agency, perhaps even more than its sister, MI5, was amateurish and inattentive to the signs of trouble in men they’d known in school.

The Human Factor by Graham Greene (1978) 288 pages ★★★★☆

Betrayal viewed through the eyes of the betrayer

Greene’s protagonist is Maurice Castle, a mid-level MI6 officer edging close to retirement. He’s one of two men, and formally the head, of a small unit specializing in Southern Africa. And he’s the mole. During his earlier service in South Africa, he had fallen in love with a young Black African woman named Sarah. She was one of his assets in the movement opposing apartheid. And when she fell under suspicion by BOSS, the South African secret police, Castle turned to a mutual friend, a Communist named Carson, to smuggle her out of the country and to safety. Castle later married her. And in gratitude he supples secret information from MI6 to a Soviet handler at Carson’s behest.

All this history becomes clear to us when Cornelius Muller, a senior official of BOSS comes to London for an official visit. And he’s he same man who had sought to imprison Sarah before she fled her homeland. To Castle’s chagrin, “C” directs him to invite Muller to his home. There, Sarah meets her erstwhile pursuer face-to-face. And the visit unfolds while a hunt for a Soviet mole in Castle’s unit is underway. Aroused by his visit to Castle’s home, Muller reports to MI6 internal security his suspicion that Castle, not his colleague, Arthur Davis, is the leak.

Summary of the novel by AI

As I frequently do, I’ve asked the chatbot Claude (version Sonnet 4.5) for a 400-word summary of this novel. What follows is the result, altered only by the subheads I’ve inserted to make the text easier to read. It’s accurate in every respect. No “hallucinations” here.

An MI6 officer with a dangerous secret

The Human Factor is a 1978 espionage novel by Graham Greene that explores themes of loyalty, betrayal, and the moral complexities of Cold War intelligence work. Unlike conventional spy thrillers, Greene’s novel focuses on the quiet desperation and ethical dilemmas of its protagonist rather than action-packed intrigue.

The story centers on Maurice Castle, a middle-aged British intelligence officer working in the African section of MI6. Castle lives a seemingly ordinary life in the London suburbs with his black South African wife, Sarah, and her young son from a previous relationship. Their domestic tranquility masks a dangerous secret: Castle has been passing classified information to the Soviets for years.

Deeply personal loyalty motivates Castle’s betrayal

Greene gradually reveals Castle’s motivations through flashbacks to his time in South Africa, where he fell in love with Sarah and witnessed the brutal realities of apartheid. When Sarah and her son were in danger, Communist operatives helped them escape to England. Out of gratitude and a genuine desire to undermine the apartheid regime, Castle began his treasonous activities—not out of ideological conviction, but from deeply personal loyalty.

When a leak is suspected in Castle’s department, MI6’s security division begins an investigation. Castle’s colleague and friend, Arthur Davis, initially falls under suspicion. The security services, led by the coldly efficient Dr. Percival, decide to eliminate Davis through an untraceable poisoning disguised as natural causes—demonstrating the moral bankruptcy of the intelligence establishment. Castle watches helplessly as an innocent man is murdered, deepening his guilt and isolation.

Stranded in Moscow

Eventually, Castle’s activities are discovered, forcing him to flee to Moscow. However, his defection brings no triumph or relief. Separated from his family and trapped in Soviet bureaucracy, Castle finds himself in a gilded cage, waiting indefinitely for the authorities to allow Sarah and her son to join him. The novel ends ambiguously, with Castle stranded in a Moscow apartment, his sacrifice seemingly meaningless.

Greene’s title refers to the unpredictable human element that disrupts the calculations of intelligence agencies. Castle’s love for his family—the human factor—drives him to betray his country, while the same quality makes his Soviet handlers suspicious of his reliability. The novel is less concerned with the mechanics of espionage than with examining how ordinary people navigate impossible moral choices in a world where loyalty to institutions conflicts with loyalty to loved ones. Greene presents a bleak vision where no side holds moral superiority, and personal integrity becomes increasingly difficult to maintain.

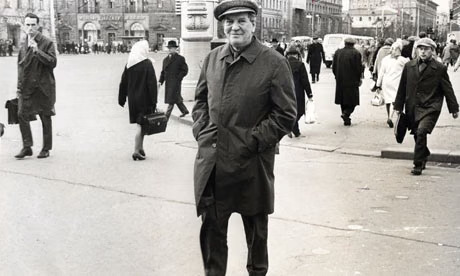

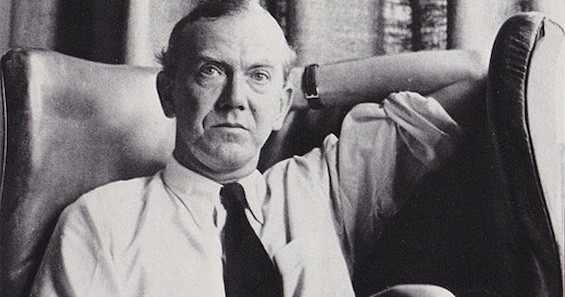

About the author

The late, great Graham Greene (1904-91) served in MI6 during World War II, although the Britannica notes only that he worked then for the “Foreign Office.” Which is the euphemism many officers of MI6 use to fend off inquiries. The facts come out in Wikipedia: “In 1941, the travels led to his being recruited into MI6 by his sister, Elisabeth, who worked for the agency. Accordingly, he was posted to Sierra Leone during the Second World War. Kim Philby, who would later be revealed as a Soviet agent, was Greene’s supervisor and friend at MI6. Greene resigned from MI6 in 1944.”

Greene wrote scores of novels and won numerous awards for the work. His career spanned the years 1929 to 1990.Most critics regard him as one of the most outstanding authors ever to turn his attention to spy fiction.

For related reading

I’ve reviewed three other Graham Greene novels:

- The Quiet American (The classic Vietnam novel by Graham Greene)

- The Comedians (Expatriates observe Haiti’s reign of terror in a classic Graham Greene novel)

- The Power and the Glory (Graham Greene’s “masterpiece” about the repression of the Mexican Church)

You’ll find other great reading at:

- The 15 best espionage novels

- Good nonfiction books about espionage

- Best books about the CIA

- The best spy novelists writing today

And you can always find the most popular of my 2,400 reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.