Estimated reading time: 5 minutes

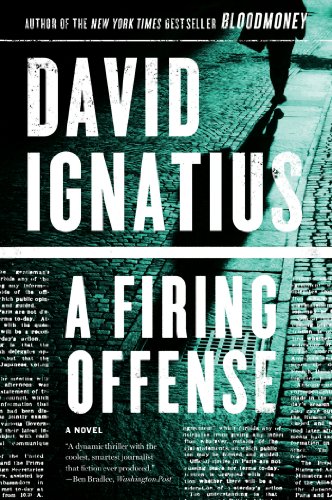

It’s not unusual for journalists to turn to writing mysteries and thrillers. After all, some of the best known names in the business began their careers in journalism, including John Sandford, Michael Connelly, and Daniel Silva. However, nothing I’ve read so far comes close to the nitty-gritty detail about the practice of journalism that Washington Post editor and columnist David Ignatius builds into in his suspenseful 1997 spy story, A Firing Offense.

A Firing Offense is a suspenseful spy story that John le Carré or Graham Greene might otherwise have written. But it’s more than that. Ignatius gives us a picture of the world in which he works and the job he does.

Reflections on journalism and espionage

Ignatius’s protagonist (his alter ego?), Eric Truell, reflects deeply on the differences between espionage and journalism. After all, he muses, “when you boiled the externalities away, we had done much the same work. We had both been in the business of gathering information—eliciting it, trading for it, teasing it out of reluctant subjects. [A CIA officer] called his informants ‘agents,’ and paid them money. I called them ‘sources,’ and gave them other kinds of rewards.” And Truell’s entanglement with the CIA and French intelligence gives him ample opportunity to ponder such questions.

A Firing Offense by David Ignatius (1997) 479 pages ★★★★★

A suspenseful spy story that involves the CIA and French intelligence

A Firing Offense opens in 1996 at the funeral of Arthur Bowman, the chief diplomatic correspondent for a major newspaper called the New York Mirror. Bowman is widely regarded as one of the country’s finest journalists. Speakers at the funeral make that clear. Yet Eric Truell knows there’s more to be known about Arthur Bowman, and that’s the tale he tells in the pages ahead.

Is a journalist being used in a covert U.S. government campaign?

The story resumes two years earlier in Paris, where thirty-five-year-old Truell is stationed as the Mirror’s Paris Bureau Chief. Acting on impulse, Truell rushes to the scene of a hostage crisis and finds a way into the restaurant where terrorists are holding fifteen diners and staff. His exclusive reporting leads him into a far darker story about French government corruption, a story that ultimately wins him a George Polk Award. And that in turn brings him into the orbit of Arthur Bowman, a legendary figure Truell had idolized. At the same time, the experience in Paris leaves him wondering whether he had unknowingly “been used in a covert campaign by the U.S. government, deliberately plotted in Washington, to change French politics.”

Who is really in charge in France?

In fact, Truell’s contact with the CIA had been more than casual. He had become involved with an officer in the CIA station named Tom Rubino. And it was Rubino who raised questions in his mind about what exactly his prize-winning story had uncovered. “Look, Eric,” he says, “the great truth of the 1990s is that the world is run by organized criminals. . . Power has slipped from governments into the hands of private organizations. In New York, private currency traders have more power over the dollar than the Federal Reserve. In Russia, the mafiya has more power than the army. In Mexico, the drug lords have more power than the president. In Japan, the politicians are just a front; the real power is held by the corporations and the yakuza.”

All of which makes Truell wonder who’s really in charge in France. He will gain some insight into the question as he tells more about Arthur Bowman.

The deplorable state of the CIA in the 1990s

Back home in a coveted new assignment in the Washington Bureau, Truell falls into a closer relationship with a disgruntled CIA officer named Rupert Cohen. Cohen’s view of the Agency is scathing. And Truell soon comes to understand just how dysfunctional the CIA has become. “These guys had been on a twenty-year losing streak,” he reflects. “They were so mired in failure that a whole generation of them had done nothing but spin their wheels. They were collapsing of their own weight, in Washington and around the world. Most of what they did nowadays was make-believe. They pretended to recruit people, wrote phony cables dressing up lunchroom gossip as secret intelligence. They were losers. They couldn’t even protect themselves of their agents.” So, Truell understands when at length he agrees to take on a mission for the Agency, that he’s likely to be on his own.

“A newspaper is like a church”

However, despite his distrust of the CIA and qualms about the newspaper he serves, Truell remains proud of his work as a journalist. “A newspaper is like a church,” he thinks. “It is built by ordinary sinners, people who in their individual lives are often petty and corrupt, but who collectively create an institution that transcends themselves. A newspaper in that way achieves a kind of divinity. It embodies the quest of its reporters and editors for an absolute—the truth. What is holy about a newspaper is the struggle of these imperfect human beings to connect with something perfect.” Which surely must reflect Ignatius’s own convictions about his career. And he has found an elegant way to share these beliefs in a suspenseful spy story.

For related reading

The author is one of The best spy novelists writing today.

You’ll find this book on The 40 best books of the decade from 2010-19.

I’ve also reviewed four other excellent spy stories by David Ignatius:

- Siro (The most intelligent spy novel I’ve read in many years)

- The Increment (A gripping novel about Iran and the CIA)

- Agents of Innocence (The CIA and the PLO in Cold War Beirut)

- Phantom Orbit (War in space may be closer than you think)

You might also enjoy my posts:

- The 15 best espionage novels

- Good nonfiction books about espionage

- The best spy novelists writing today

- Top 10 mystery and thriller series

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.