When you challenge the historical consensus fundamental to our understanding of the past, you’d better be prepared for trouble. And that’s exactly what Robert Stinnett got when he published Day of Deceit, purporting to tell the truth about Pearl Harbor. Picking up on a charge long ago rejected by most historians, he claimed that President Franklin D. Roosevelt knew the Japanese were about to attack Pearl Harbor and deliberately withheld the information from the admiral in charge there. When Stinnett’s book was published in 1999, the New York Times review was typical: “Despite a dogged and sometimes compelling effort . . . Stinnett has produced no ‘smoking guns'” to substantiate his arguments. Established historians piled on, questioning the reliability of some of his sources and rejecting the evidence he produced to support his conclusions.

Estimated reading time: 7 minutes

When did the US Navy break the Japanese naval codes?

The most explosive arguments in Stinnett’s exposé largely rest on a single crucial assertion: that months before Pearl Harbor, US Navy codebreakers had unraveled the Japanese naval codes and were already intercepting and decoding the Empire’s naval traffic at a furious pace. Most historians (and the US Navy) insist that the Japanese observed radio silence on the way to Hawaii and that, in any case, the decoding breakthrough didn’t come until after the Japanese attack—and just in time to enable the Navy to achieve a great victory at the Battle of Midway in June 1942.

How, then, could Stinnett produce a veritable flood of dated and decoded intercepts that clearly document the progression of the Japanese fleet toward Hawaii in late November and early December 1941? And were the Navy men who showed the evidence to the author—and the documents themselves—all lying? Were these his “unreliable sources?” After all, most were enlisted men, contradicting the testimony of US Navy officers. Should we believe that only enlisted men lie and officers never do?

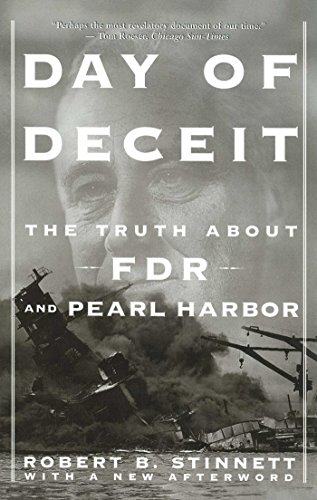

Day of Deceit: The Truth About FDR and Pearl Harbor by Robert B. Stinnett (1999) 416 pages ★★★☆☆

What does Stinnett actually prove?

No “smoking guns” indicting the President

Stinnett never succeeds in proving some elements of his case. He repeatedly insists that FDR “knew” about matters that most historians claim he could never have known. In numerous instances, Stinnett notes that information about the impending attack on Pearl Harbor was sent to the White House. It’s highly probable that Roosevelt did read at least some of those documents and thus did know what others there clearly did. But the author produces no documentary evidence of that. Nor is there anything to substantiate the claim the President ordered that the commander of the Pacific Fleet be kept in the dark.

It’s true that Admiral Husband Kimmel in Hawaii was indeed ignorant of the information unlocked in those radio intercepts. And it appears that some naval officers did fail to send it to him. But there is no visible link to the President. As the New York Times complained, there are no “smoking guns” here.

A “shocking new American foreign policy”

However, Stinnett’s obsession to prove that FDR knew in advance about the Pearl Harbor attack obscures his more important discovery: the McMahon memo. Lt. Commander Arthur H. McMahon was head of the Far East desk of the Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI). Addressing his boss at ONI—a close advisor of the President—on October 7, 1940, he “suggested a shocking new American foreign policy. It called for provoking Japan into an overt act of war against the United States. . .” It was “a plan intended to engineer a situation that would mobilize a reluctant America into joining Britain’s struggle against the German armed forces then overrunning Europe.”

If the McMahon memo were merely another piece of paper in a government swimming in documents, it could be dismissed. But the officer recommended eight steps that “called for virtually inciting a Japanese attack on American ground, air, and naval forces in Hawaii, as well as on British and Dutch colonial outposts in the Pacific region.” And the United States government implemented every one of those eight steps in 1940 and 1941, forcing Japan to go to war. It is unimaginable that the country could have pursued that course without the express approval of the President. Again, however, there is no documentary proof he did so.

Aggressive military moves calculated to enrage Japan

Previously, historians have written that the US decision in 1940 to embargo oil to Japan foretold war. But, as Stinnett shows, there were loopholes in the embargo, and it was not widely enforced. Millions of barrels of oil continued to flow to Tokyo. As one of the eight actions he counseled, McMahon called for the US to “completely embargo all trade with Japan, in collaboration with a similar embargo imposed by the British Empire.” And the other seven actions represented aggressive military moves perfectly calculated to enrage the Japanese leadership. It worked.

In other words, Stinnett does prove that the United States government—undoubtedly acting under orders from FDR himself—effectively started the war in the Pacific.

Unmasking the truth about Pearl Harbor

Little of what Stinnett writes in Day of Deceit came to him easily. Over a period of seventeen years, he conducted archival research and personal interviews with US Navy cryptographers. And he repeatedly used the Freedom of Information Act to uncover “secrets that had been hidden from Americans for more than fifty years.” The evidence appears throughout the pages of Stinnett’s book, which includes innumerable and extensive quotes from the decoded radio intercepts of Japanese naval traffic. They prove conclusively that the fleet attacking Pearl Harbor did not observe radio silence. And the fact that they lay under lock and key in Navy files for so many years doesn’t smell right. After all, if something looks like a coverup and smells like a coverup, what else could it be?

A poorly written piece of work

Unfortunately, Stinnett was an appallingly bad writer. The book is chaotically organized and full of annoying and unnecessary repetition, often from one page to the next. His prose is clear enough, for the most part, but it is exceedingly difficult to follow the threads of the story he tells, because he unaccountably chose not to lay it out chronologically. Had a better writer produced this book, it seems likely Stinnett’s findings would have been more favorably received. As it is, most critics panned the book. A review in the March/April issue of Foreign Affairs is typical.

About the author

The late Robert Stinnett (1925-2018) served as a US Navy photographer from 1942 to 1946. He participated in ten battles in the Pacific in World War II. For much of his career, he worked as a photographer for the Oakland Tribune in Oakland, California. In addition to Day of Deceit, he wrote a biography of the first President Bush, George Bush: The War Years. (He had served under Lt. George H. W. Bush in the war.) During at least some of the years when he researched Day of Deceit, Stinnett was a Research Fellow at the Independent Institute in Oakland.

For more reading

You’ll find a wealth of additional information about World War II at:

- Books about World War II in the Pacific

- 10 top nonfiction books about World War II

- 7 common misconceptions about World War II

- The 10 most consequential events of World War II

- Top 20 popular books for understanding American history

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, plus a guide to this whole site, on the Home Page.