Estimated reading time: 6 minutes

In The Secret War, his revisionist history of intelligence in World War II, British historian Max Hastings insists that spies, special forces, and resistance fighters had little impact on the outcome of the war. He makes the case that the Allies’s decoding of German and Japanese secret codes was far more significant in ending the war. Hastings points in particular to the penetration of the two belligerents’s naval codes that helped end the wars at sea in both the Atlantic and the Pacific. I found his argument persuasive.

Did special forces play a decisive role in World War II?

Yet I still can’t resist reading more of the innumerable books that lionize the French Resistance and British and American spies on the Western Front. There’s something deeply satisfying about the stories of the courageous women and men who led the Resistance in France and funneled a torrent of intelligence to London in the run-up to the Normandy landing. And it’s difficult to read these books without wondering whether Max Hastings didn’t protest a little too much. For example, Sarah Rose‘s D-Day Girls shows more clearly than I’ve read elsewhere how extensive these efforts were. Human intelligence and the resistance involved not handfuls of brave individuals but hundreds of thousands of people in an intensive campaign the Germans were forced to devote thousands of troops to combat.

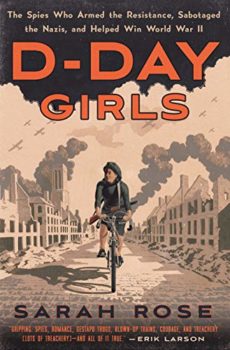

D-Day Girls: The Spies Who Armed the Resistance, Sabotaged the Nazis, and Helped Win World War II by Sarah Rose (2019) 372 pages ★★★★☆

Special forces behind the lines in France

D-Day Girls spotlights the British Special Operations Executive (SOE), the world’s first large fighting force trained and organized to operate behind enemy lines. And its operations were truly large:

- “Some 429 agents went behind the lines, suffering 104 casualties; together with de Gaulle’s RF Section, they armed the whole of occupied France,” Rose writes. “In total, Allied-backed resistance forces were counted as worth fifteen divisions in France, or about 200,000 troops.”

- And just “between December 1942 and January 1943, some 282 German officers were killed by partisan activity [in France], 14 trains were wrecked, 94 locomotives and 436 coaches were destroyed, 4 bridges went down, 26 trucks were destroyed, there were 12 major strategic fires, and 1,000 tons of food stores and fuel were destroyed.” All these operations were going on as Hitler’s forces fought for their lives in Stalingrad. It’s clear to me that Allied efforts behind the lines in France must have tied up large numbers of German soldiers who might otherwise have turned the tide a continent away in Russia. And keep in mind that the Russian victory in the Battle of Stalingrad is widely agreed to have been the turning point in the European war.

The women in the world’s first special forces

Author Sarah Rose pays special attention in D-Day Girls to a handful of women in the French Section (F Section) of the SOE. But throughout she puts their experiences in the larger context. “Women made up some two thousand of the approximately thirteen thousand employees of the Special Operations Executive . . . They were translators, radio operators, secretaries, drivers, and honeypots. Only eight were deployed as special agents in Autumn 1942, when SOE’s first class of female trainees was seconded to France.”

Six courageous women who helped pave the way for the Normandy landing

It’s that larger context that underlines just how extraordinary were the women whose stories Rose relates. “Among their many firsts, they were the first women in organized combat, the first women in active-duty special forces, the first women paratroopers infiltrated into a war zone, the first female commando raiders, the first women signals officers behind enemy lines; they were the first to write women into the history of war.” And the individual stories of six individual women are dramatic, sometimes tragic, but always moving. It’s worth noting their names: Odette Sansom, Andree Borrell, Lise de Baissac, Yvonne Rudelat, Helene Aron, and Mary Herbert. It’s also worth noting that decades after the end of the war their contributions and sacrifices went largely unacknowledged by the British and French governments.

Special forces today around the world

It’s hard not to think that the SOE (and later the American OSS) didn’t have considerable impact in World War II. After all, what do they say about imitation and flattery? Today virtually every country in the world that maintains an army has at least one unit of special forces, and often several. In the US those special forces include Navy Seals and Delta Force, among many others. Russia has its Spetsnaz; China, the Special Operations Forces of the People’s Liberation Army; the British, Special Air Service; France, the Special Operations Command. In fact, scores of countries field numerous special forces units, typically attached not just to their armies but to their navies and air forces as well.

For related reading

This book is a runner-up to the 10 top WWII books about espionage and is one of 10 true-life accounts of anti-Nazi resistance.

I’ve also reviewed several other nonfiction books about the SOE and the French Resistance:

- Code Name: Lise: The True Story of the Woman Who Became World War II’s Most Highly Decorated Spy by Larry Loftis (A woman was World War II’s most highly decorated spy);

- Madame Fourcade’s Secret War: The Daring Young Woman Who Led France’s Largest Spy Network Against Hitler by Lynne Olson (The truth about the French Resistance, dug out of old records);

- A Woman of No Importance: The Untold Story of the American Spy Who Helped Win World War II by Sonia Purnell—The WWII American woman spy who kept the French Resistance alive; and

- Rogue Heroes: The History of the SAS, Britain’s Secret Special Forces Unit that Sabotaged the Nazis and Changed the Nature of War by Ben MacIntyre (The story of the original special forces).

I’ve also read and reviewed three excellent novels about the French Resistance:

- The Nightingale by Kristin Hannah (A deeply affecting novel of the French Resistance);

- Red Gold (Night Soldiers #5) by Alan Furst (A brilliant novel of the French Resistance); and

- A Hero of France (Night Soldiers #16) by Alan Furst (Vive la Resistance!).

You might also be interested in 10 top nonfiction books about World War II and The 10 best novels about World War II.

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.