Today’s widening gap between rich and poor—the billionaires versus the rest of us—is often compared to that in the Gilded Age. Then, the parties involved were the Robber Barons at society’s pinnacle and the working men and women whose labor generated the obscene wealth the rich displayed with such abandon. But the comparison goes only so far. And that’s just one of the insights that emerges loud and clear from Jack Kelly’s superb book about organized labor and the 1894 Pullman Strike he aptly calls “the greatest labor uprising in America.”

Estimated reading time: 8 minutes

In the great Depression of 1893, workers were on the verge of starvation

In the 1890s, especially during the Depression of 1893-97, millions of hardworking Americans were living in destitution. They were often on the verge of starvation—despite holding full-time jobs. However deplorable the lot of millions of us today in the United States, few are starving. Similarly, the widespread racism and xenophobia that leads to hate crimes and death by cop today is but a pale reflection of the raw, aggressive racism expressed in Jim Crow and the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. Things are bad today for many. But they were far worse, and for a much larger proportion of society, in the closing years of the 19th century.

In The Edge of Anarchy, Jack Kelly makes all that transparently clear. His book chronicles the efforts of early organized labor to harness the anger and frustration of working people in an assault on the stranglehold the country’s richest men held on the businesses they owned—and on the government they had bought and paid for.

The Edge of Anarchy: The Railroad Barons, the Gilded Age, and the Greatest Labor Uprising in America by Jack Kelly (2019) 304 pages ★★★★★

A Gilded Age melodrama with its hero and its villain

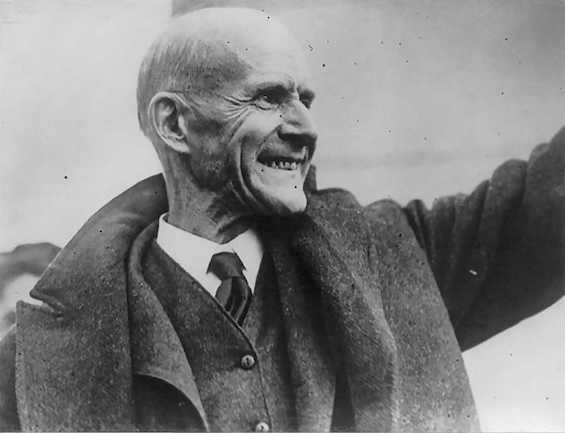

If this book were a novel, its hero would be Gene Debs—that’s Eugene V. Debs (1855-1926), organizer of the American Railway Union and future five-time Socialist candidate for President of the United States. And the villain in this Gilded Age melodrama was George Pullman (1831-97), the engineer who designed and manufactured the Pullman sleeping car. He had also founded the model company town, Pullman, Illinois, which was “one of Chicago’s premier tourist attractions.”

Pullman “set the tone for the era”

George Pullman rose to prominence and great wealth in an era when the railroads were by far the nation’s biggest business enterprises. His company contracted with many of them to furnish and staff luxurious cars where well-to-do passengers could travel and sleep in comfort. The industry’s position in society was comparable to that of high-tech today. Some 750,000 men and women worked on the railroads at a time when the nation’s population was less than one-fifth what it is today. By comparison, Walmart and Amazon together employ a total of 2.7 million people in the US today.

As Jack Kelly notes, “George Pullman helped set the tone for the era . . .” His palatial home “contained a two-hundred-seat-theater, a billiard room, a bowling alley, a pipe organ, and a palm room with a leaded-glass door . . . He and his wife, Hattie, threw parties there for four hundred guests.”

As the company flourished, workers were desperate

Meanwhile, it was well known that “Pullman’s Palace Car Company was hoarding $25 million in surplus profits and had contributed another $4 million during 1893 alone. Even in 1894″—during the steepest depression in American history to that point—”the company as a whole had turned a healthy profit.” Yet when workers at Pullman called a strike in December 1893 to protest a 25 percent pay cut, Pullman refused to negotiate with them or even countenance arbitration.

For most of Pullman’s employees, pay was measured in pennies per hour and rarely topped a few dollars per week. Against these starvation-level wages, they had to pay the exorbitant rents Pullman charged for their homes in his model town. A local minister noted that “One man has a pay check in his possession of two cents after paying rent.”

The emergence of industrial unionism

Gene Debs, the apostle of organized labor in the 1890s, could hardly have provided a greater contrast to George Pullman. Both had been born and raised in small towns, Debs in Terre Haute, Indiana, Pullman in Brocton, New York. Debs’ family was comfortably middle-class, Pullman’s poor. But from an early age each set out on the path that led them to face off in a strike that helped define the era. While Pullman began building a fortune in the business community, Debs went to work for the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen, one of many craft unions then established in the railroad industry. He worked for the union for many years until elected for a term to the Indiana General Assembly.

Debs concluded that craft unionism divided workers and was unable to take on the larger forces arrayed against working people. To build a base of support among them large enough to confront the power of the railroads, he founded the American Railway Union in 1893. It was the country’s first industrial union. As the depression gathered steam, the ARU quickly grew to 150,000 members, nearly equal in size to the well-established American Federation of Labor (AFL). The AFL, led by Samuel Gompers, housed an association of craft-based unions like Debs’ old Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen. The ARU’s organizing drive prefigured that of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), which came into existence forty years later.

The third major player in the drama

Grover Cleveland, then serving his second term as President of the United States, weighed in with all the might of the federal government in support of George Pullman and the General Managers Association uniting railroad executives against the ARU. Cleveland “had filled his administration with businessmen, bankers, and Wall Street speculators.” His attorney general, Richard Olney, had previously served as general counsel for one of the nation’s leading railways and served on the boards of several other railroads while in office. It was he who spearheaded the attack on the strikers.

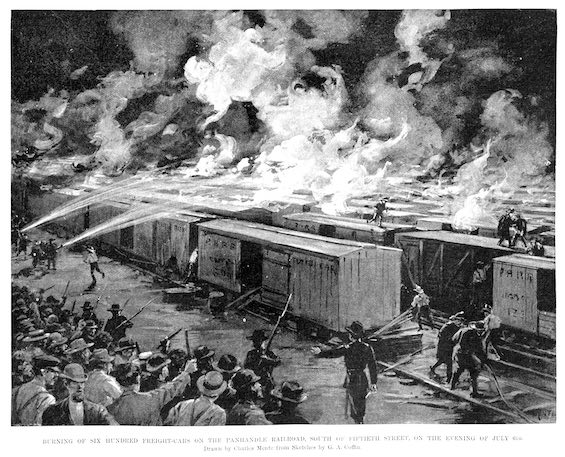

In the face of Pullman’s intransigence, the momentum of what had been a local strike by just some of his employees spread, first, to most of the company’s remaining workers. Then, when Debs’ American Railway Union became involved, hotheads in the organization defied Debs’ insistence on a cautious approach and voted to spread the strike nationwide. The effort caused great hardship around the country, stranding thousands of railway passengers, causing tons of perishable food to rot in boxcars, and leading to outbreaks of violence. Eventually, the most aggressive members of the ARU forced a vote for a general strike that would have paralyzed the nation. Debs was heartbroken but professed support. He was, however, right to have been cautious. The general strike failed to catch on, even in Chicago, where support had appeared to be most enthusiastic. Thus, the “greatest labor uprising in America” proved to be abortive.

About the author

Jack Kelly‘s author website describes him as “a public scholar, a historian and a novelist. . . The Baltimore Sun described Jack’s writing as ‘brilliantly succinct and excruciatingly powerful.’ The Wall Street Journal wrote that he ‘packs in a remarkable amount of information, thanks to his lean, readable prose.’ A New York Foundation for the Arts fellow, Jack has appeared on NPR, PBS, and The History Channel. He has written for national publications including the Wall Street Journal and American Heritage. Born in Western New York, Jack now lives and works in the Hudson Valley.” The website lists a total of five nonfiction books.

For related reading

This book is among The best nonfiction of 2022.

For a superb work of nonfiction that casts additional light on the early labor struggle, read Rebel Cinderella: From Rags to Riches to Radical, the Epic Journey of Rose Pastor Stokes by Adam Hochschild (Early 20th-century America viewed through the life of one extraordinary woman). There is a less successful history of labor in From the Folks Who Brought You the Weekend: An Illustrated History of Labor in the United States, Revised and Updatedby Priscilla Murolo and A. B. Chitty (A brief and bloody history of labor in America).

You’ll find an excellent fictional treatment of labor-management strife during the early years of the 20th century, see The Cold Millions by Jess Walter (A gripping tale about the early American labor movement).

For other highly readable books on related subjects, see:

- Top 20 popular books for understanding American history

- 20 top nonfiction books about history

- Top 10 nonfiction books about politics

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, plus a guide to this whole site, on the Home Page.