Most accounts of the British-American alliance in World War II dwell on the closeness between Winston Churchill and Franklin Roosevelt. But a more fine-toothed inspection of history reveals that others played equally significant roles in making the relationship work. And historian Lynne Olsen has dug into contemporaneous accounts, dredging up eye-opening facts about three prominent Americans whose wartime careers were pivotal in forging and sustaining the bond. US Ambassador John Gilbert Winant. Lend-Lease administrator W. Averell Harriman. And CBS radio broadcaster Edward R. Murrow. In Citizens of London, she follows these three remarkable men throughout the war, tracing the many ways they eased (or sometimes complicated) the relationship between the two powerful Western Allies. Her account is at times jaw-dropping. If a work of history can be a page-turner, Citizens of London fits the bill.

Citizens of London: The Americans Who Stood with Britain in its Darkest, Finest Hour by Lynne Olson (2010) 599 pages ★★★★★

Three men play starring roles

In Citizens of London, Lynne Olson spotlights the often heroic efforts of many Americans who spent much of the war in the British capital. The book is full of engaging stories about many of them. But she focuses on three prominent men who were most influential in forging and sustaining the British-American alliance.

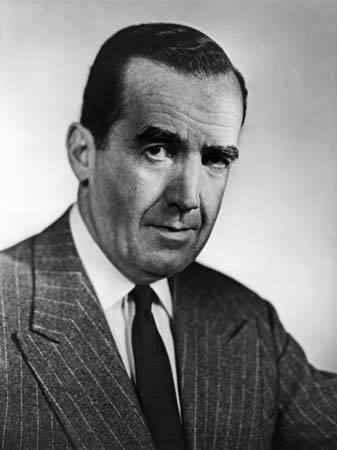

Ed Murrow

Edward R. Murrow (1908-65) needs no introduction to anyone in the United States over the age of sixty. He is widely regarded as the father of broadcast news in America, which he pioneered as a young man in London shortly before and during World War II. For decades, his distinctive deep voice was familiar to anyone who followed the news on the radio—and, later, on television. Today, he is best remembered for attacking Senator Joseph McCarthy and the Red Scare on his 1954 TV broadcast of See It Now. But for the oldest Americans—and for a generation of now-elderly Britons—it was Murrow’s eloquent and compelling live broadcasts on CBS Radio during World War II that most lingers in the mind. He is venerated among journalists for his honesty and integrity in delivering the news.

Averell Harriman

W. Averell Harriman (1891-1986) was often described as the fourth richest man in America. He was the son of Union Pacific Railroad tycoon E. H. Harriman, one of the original Robber Barons. But, after his early years, when he made a name for himself as a polo champion and an inveterate womanizer, Harriman gained an appetite for public service.

FDR spurned his early requests for a key position, first in the New Deal and then in the war. But in 1941 the President enlisted him as his personal representative to the British government, operating officially as “Expediter” of Lend-Lease aid to Britain. Later, Roosevelt named him US Ambassador to the Soviet Union, where he served as the Cold War began. However, generations of Americans may know his name as one of the six “Wise Men” who framed American post-war diplomacy and guided the nation through the first two decades of the Cold War. (Others included Dean Acheson, George F. Kennan, and John J. McCloy.) He also served a term as Governor of New York in the 1950s.

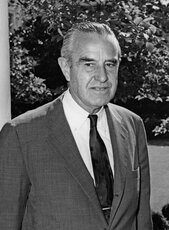

Gil Winant

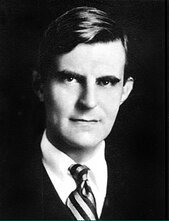

Today, John Gilbert Winant (1889-1947) is far less well remembered than Ed Murrow and Averell Harriman. But for decades beginning in the 1920s he was one of the leading figures in the American Establishment. Born to wealth and privilege, he gained fame throughout the country as the hard-working, three-term Governor of New Hampshire. A maverick Republican, he built his career on an intimate, even magical relationship with working people.

Winant was touted as the man to run against FDR in the 1936 Presidential election. But as a stout supporter of the New Deal, he jettisoned his political career by joining the Administration. On March 1, 1941, Franklin Roosevelt named him Ambassador to the Court of St. James, and he remained in that post until April 10, 1946. During those five years, Winant personified the bond between the United States and Great Britain. More than any other individual, he made the British-American alliance work. He gained a place in the hearts of the British people like that he had forged with his New Hampshire constituents. His death by suicide in 1947 was mourned as a tragedy throughout Britain.

The ups and downs of the British-American alliance

Olson’s story spotlights the experiences of these three men during the Blitz (September 1940 – May 1941) and the tumultuous years that followed. She argues that it was they, living and working in London, who made the special relationship work. At first, Churchill and Roosevelt got along poorly. They warmed to each other in part as a result of the shrewd advice both Winant and Harriman gave Churchill, with whom both men spent most weekends in the countryside. And the resentment and distrust melted away after Pearl Harbor. But the intimate connection celebrated in popular history books relates only to the first year and a half after the US entry into the European war (December 11, 1941). Soon, however, American troops were pouring onto the field, and the “arsenal of democracy” had begun churning out overwhelming numbers of airplanes, tanks, and ships. As a result, Roosevelt gained the upper hand.

The two leaders met at the Casablanca Conference in January 1943 to discuss the next steps after the British-American triumph in North Africa. Olson notes, “Casablanca would mark the final time in the war that Britain would get its way over strategic objectives—or much of anything else.” More and more, Winston Churchill felt himself shunted to the sidelines. But Winant and Harriman, together with a handful of Britons, managed to bottle up Churchill’s rage and resentment. And Harriman and his patron, Presidential confidante Harry Hopkins, worked to tamper down Roosevelt’s impulsive and sometimes wrongheaded decisions. Together, those efforts ensured that the alliance didn’t fly out of control despite the increasing gap in power and influence between the two principals.

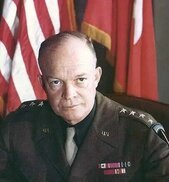

Dwight Eisenhower

But there was a fourth actor on the stage whose later, starring role overshadowed theirs for a time. General Dwight D. Eisenhower (1890-1969) arrived in London early in 1944 to launch the Normandy Invasion. The decision to appoint “Ike” was FDR’s alone. Churchill and the British military establishment resented deferring to a man who had only attained the rank of colonel in 1941, “had never commanded an Army unit larger than a battalion and had never fought in a war” before the invasion of North Africa in November 1942. (For years, Eisenhower had served as aide to General Douglas MacArthur, who derisively referred to him “the best clerk I ever had.”)

Throughout the war, Churchill and the most senior British generals continued questioning and undermining Eisenhower. Chief of the Imperial General Staff Alan Brooke (1883-1963) and General (later Field Marshal) Bernard Montgomery (1887-1976) were both outspoken in opposition to the American commander. And they set the tone for unrelenting bickering between the staff officers of the two nations. But Eisenhower “was one of America’s few generals who was not an Anglophobe.” Only his superlative diplomatic skills saved the day.

Romantic involvements

The British-American alliance took shape on an intimate level as well. It’s well known that General Eisenhower became involved with his Irish driver and later personal secretary, Kay Summersby. Some speculate they carried on an affair, although those who knew the general rejected the claim. However, the other three stars of this story all became involved with British women—and both were members of Winston Churchill’s family.

Gil Winant fell deeply in love with the Prime Minister’s oldest daughter, the actress Sarah Churchill (1914-82). And Ed Murrow carried on an affair with Churchill’s daughter-in-law, Pamela Churchill (1920-97), the wife of the Prime Minister’s son, Randolph. (Randolph was “a blustering bully whose drinking, gambling, and womanizing were a constant source of embarrassment for his parents.”) But Murrow’s involvement with Pamela followed Averell Harriman’s passionate, two-year affair with her; although the two went their separate ways when he left to take up his post as US Ambassador to the Soviet Union, they met again in the United States decades later and married when Harriman was seventy-nine years of age and Pamela was fifty-one.

A wide range of leadership skills

Olson skillfully chronicles the parallel stories of these three, and later four, Americans who drove the Atlantic partnership.

Ed Murrow

Ed Murrow’s eloquent broadcasts during the Blitz conveyed to the American public the desperate human reality in London and other British cities under the onslaught of Nazi bombing raids—and helped shift the isolationist US public toward a willingness to intervene in the war. Murrow’s boss at CBS, William Paley, had “decreed that analysis would be allowed on his network, but not opinion. Murrow made mincemeat of that policy from the start. . . ‘He made no pretense about being neutral or objective,’ Eric Sevareid observed.”

Gil Winant

While the bombs fell and sirens wailed, Gil Winant wandered through the streets of London at night, helping those in need. He befriended the humblest of British citizens, often keeping the rich and powerful waiting to meet with him. He repeatedly persuaded Winston Churchill to toss out or soften the angry cables he had drafted to send Franklin Roosevelt. “More than once,” Olson remarks, “Churchill sent [his private secretary] to the embassy to have Winant vet his speeches.” And, at the behest of the Labour Party, Winant persuaded coal miners to call off a strike that threatened to upend the war effort. “If you talked to the textile workers of Lancashire or the shipyard workers along the Clyde, they would say, ‘We know Winant—he’ll never let us down.'” And a day after his talk with the miners, a banner headline in the Daily Express read ‘WINANT TALKS, STRIKE ENDS.'”

Averell Harriman

Averell Harriman became one of Churchill’s closest advisers, opening an alternate channel between the two nations’ leaders. He was at the Prime Minister’s side—not Roosevelt’s—during most of the crucial summit conferences in 1941 through 1943.

Dwight Eisenhower

And, much later, Dwight Eisenhower held the alliance together through his patient insistence to his rebellious generals that the British must be treated as equals. Few other men, and perhaps no one, could have managed the prima donnas (Patton, Bradley, Brooke, Montgomery) whose leadership was vital to Allied victory. “Eisenhower likened the early relationship between the two nationalities on his staff to ‘the attitude of a bulldog meeting a tomcat.'” Most of the British, and a few Americans as well, feared that Operation Overlord would founder on the beaches of Normandy. It was Eisenhower’s unflagging energy that held the British-American alliance together through the difficult early days of the campaign.

An account that’s full of surprises

Olson keeps the pages turning in Citizens of London with a fresh eye on revealing detail. Thus, Citizens of London abounds with surprises. Here are just three examples.

The high price Britain paid the US for 50 obsolete destroyers

At a remove of more than three-quarters of a century, the story of World War II has become boiled down to essential facts in most accounts. For example, we are taught that a 1940 agreement FDR negotiated with Winston Churchill involved the trade of some fifty World War I-era American destroyers for 99-year leases on military bases in Newfoundland and the Caribbean. But that’s not the whole story.

“In addition to the bases,” Olson explains, “Britain handed over to the U.S. military its blueprints for rockets, gun sights, and new Merlin engines; early-stage plans for the jet engine and atomic bomb; and prototypes for a radar system small enough to use in aircraft. Several of these advances would play a key role in the Allied effort to come.” Small wonder that Winston Churchill thought he had been had, especially after many of the destroyers showed up needing weeks of work in port before they could be operational.

Britain’s MI6 was nearly dysfunctional in Europe

Late in 1939, Olson reveals, two Secret Intelligence Service (MI6) agents had fallen into a German trap. Under interrogation, “the agents readily revealed details of the agency’s operations, including names of SIS operatives throughout Western Europe.” As a result, it was European spy services that obtained nearly all the operational information. “In 2005, the British government acknowledged that nearly 50 percent of the secret information obtained by the Allies from wartime Europe came from Polish sources.” And the breakthrough against the German Enigma code was not a British effort alone. “Bletchley Park could not have done it without the help of the French and, above all, the Poles.”

Polish troops and partisans played large roles

Polish pilots

“By 1943, some 100,000 European pilots, soldiers, and sailors had fetched up in Britain,” Olson notes. Already, Polish pilots had far outnumbered those from other nations in RAF Fighter Command‘s defense of the island in 1940. “According to top RAF officials, the contributions of the Poles were crucial to the Battle of Britain victory; some believe it was decisive.”

Polish resistance

And, contrary to the impression in English-language accounts of the resistance on the Continent, which lionize the French and Britain’s Special Operations Executive, it was the Polish Resistance that was “the largest and most highly developed underground movement in Europe.” The Poles were “responsible for massive delays and disruptions of German rail transports through Poland to the eastern front, thus contributing to the collapse of the German offensive against the Soviet Union.”

About the author

Journalist and historian Lynne Olson (born 1949) has written seven books on the history of the World War II era. As the bio on her website reveals, She was “born in Hawaii [and] graduated magna cum laude from the University of Arizona. Before becoming a full-time author, she worked as a journalist for ten years, first with the Associated Press as a national feature writer in New York, a foreign correspondent in AP’s Moscow bureau, and a political reporter in Washington. She left the AP to join the Washington bureau of the Baltimore Sun, where she covered national politics and eventually the White House. Olson lives in Washington, DC with her husband, Stanley Cloud, with whom she co-authored two books.”

For additional reading

For another superb book about London during the war, see The Splendid and the Vile: A Saga of Churchill, Family, and Defiance During the Blitz by Erik Larson (An intimate view of Winston Churchill in WW2). See alsoThe Daughters of Yalta: The Churchills, Roosevelts, and Harrimans, a Story of Love and War by Catherine Grace Katz (The Yalta controversy and the fate of Poland). And for another perspective on the British-American relationship early in the Second World War, see Agents of Influence: A British Campaign, a Canadian Spy, and the Secret Plot to Bring America into World War II by Henry Hemming (British interference in American politics in WWII).

I’ve reviewed a later work by Lynne Olson, Madame Fourcade’s Secret War: The Daring Young Woman Who Led France’s Largest Spy Network Against Hitler (The truth about the French Resistance, dug out of old records), which I also found to be excellent.

You might also be interested in:

- 10 top nonfiction books about World War II (plus many runners-up)

- The 10 best novels about World War II (with 30+ runners-up)

- 7 common misconceptions about World War II

- The 10 most consequential events of World War II

- Top 20 popular books for understanding American history

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, plus a guide to this whole site, on the Home Page.