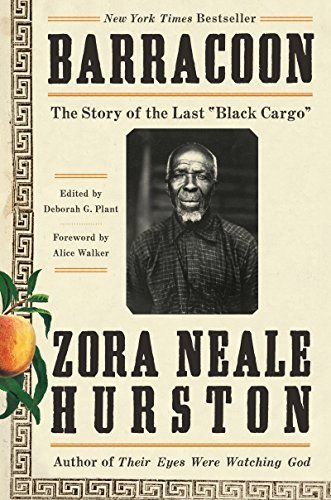

From 1927 to 1931, cultural anthropologist and folklorist Zora Neale Hurston interviewed the last living former slave in the United States and prepared an account of his life for publication. The manuscript never found a taker until 2018, when acclaimed novelist Alice Walker arranged for it to be brought into the light of day. We’re deeply indebted to her for the effort. Hurston’s book offers us an eloquent and moving tale that adds heft to our understanding of our past. Barracoon: The Story of the Last “Black Cargo” brings a personal dimension to the slave trade, the lived experience of slavery in the US, and the violent years that followed for African-Americans during nearly a century after emancipation.

Estimated reading time: 7 minutes

A slave for “five years and six months”

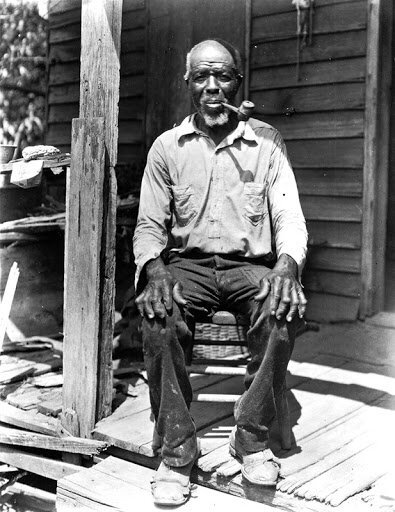

Kossola—renamed Cudjo Lewis in Alabama—was eighty-six years old when Zora Neale Hurston showed up in Africatown (Plateau), Alabama, to interview him for the Journal of Negro History. He was, after all, the last living former slave and his story cried out to be told. Born on or around 1841 and captured by slavers at the age of nineteen, he was force-marched to the coast and imprisoned with hundreds of others in one of the many barracoons where slaves were interned before sale to white men. (The word is derived from the Portuguese and means “barracks.”)

Barracoon: The Story of the Last “Black Cargo” by Zora Neale Hurston (2018) 210 pages ★★★★☆

Once landed in Alabama, Kossola then lived as a slave for “five years and six months.” To chronicle his story, Hurston returned again and again over a period of three months, gradually piecing together Kossola’s heart-wrenching tale. The man had a truly remarkable memory and could summon up precise dates, names, and conversations from nearly nine decades in the past, much of which was confirmed by independent sources. The result is a gripping account that spans nearly a century of our national shame.

The last living former slave speaks in his own voice

A folklorist by training as well as inclination, Hurston carefully reproduces Kossola’s fractured English in the extensive quotes that form the basis of her account. For example, she reports him saying at the outset, “When I come away from Afficky I only a boy 19 year old. . . We come in de ‘Merica soil naked and de people say we naked savage. Dey say we doan wear no clothes. Dey doan know de [African porters] snatch our clothes ‘way from us.” There is a certain charm, and doubtless authenticity, in this practice. It’s easy to hear the man talking as you read.

Sixty-seven years of oppression

When Hurston interviewed Kossola, the Civil War had been over for sixty-two years. Thus, Kossola’s experience in the United States was largely that of Reconstruction and the era of Jim Crow that followed. Unsurprisingly, he and his family fell victim to some of the worst practices of the time. Kossola and his wife had five children, but she and all five were long dead when Hurston met him.

One of their four sons was shot to death without warning by a deputy sheriff who had lain in wait for him at a local store. A second son disappeared one day and most likely met a horrible death as well. Kossola himself was struck by a train and injured badly enough that he was unable to work again—and one of his sons was killed in a similar “accident” not long afterward. (A court found the railroad liable for Kossola’s injury and ordered the company to compensate him, but “Cudjo doan gittee no money.”) Yet somehow he survived, lonely though he was. His church employed him as sexton. He died in 1935 at the age of ninety-four or ninety-five.

The African role in the slave trade

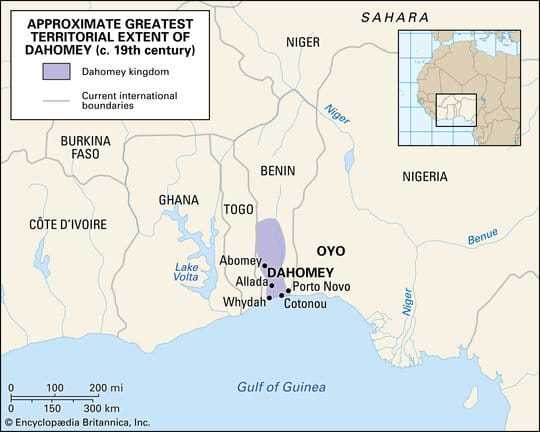

What is most remarkable about Barracoon is Kossola’s detailed account of the nighttime attack on his village in which his entire family was slaughtered and he was bound off to the coast as a slave. Hurston certainly found this surprising. “The inescapable fact that stuck in my craw,” she wrote, “was: my people had sold me and the white people had bought me.” And it’s hard to overlook the savagery and cynicism of the attack by the soldiers of the King of Dahomey. As Kossola explains, Dahomey was unlike other societies in the region in that its principal income derived not from agriculture but from slaving. As Alice Walker notes in her foreword, “this is, make no mistake, a harrowing read.”

The slave trade

According to Canadian historian Paul Lovejoy, a specialist in African history and the diaspora, “the estimated number of Africans caught in the dragnet of slavery between 1450,” when the Portuguese brought the first large number of slaves from Africa to Europe, “and 1900 was 12,817,000.” Only 10.7 million of them survived the dreaded Middle Passage. Brazil—long a Portuguese colony—received the largest proportion of them, an estimated total of 4.9 million. A surprisingly small percentage arrived in the United States: estimates range as low as 388,000 and as high as between one and two million. Yet by 1900, African-Americans numbered 8.8 million, or nearly twelve percent of the country’s population. Kossola may have been the last living former slave in the United States, but millions of others or their immediate families had shared much of the same experience.

Kossola was enslaved and transported to the United States in 1859. He was one of 110 captives from the present-day nation of Benin who constituted what was reportedly “the last black cargo” to arrive in the United States. Half a century earlier, the slave trade had been abolished in both Britain (1807) and the US (1808). In fact, the Clotilda—the ship that bore Kossola to America—lay hidden for more than two months to avoid detection by Federal authorities. In the end, the ship’s captain failed. The three brothers who were his partners in the venture “were tried in the federal courts in 1860-61 and fined heavily for bringing in the Africans.” However, they had succeeded in spiriting the slaves off to the plantations they owned in the area.

About the author

Zora Neale Hurston (1891-1960) was one of the leading lights of the Harlem Renaissance. She was a cultural anthropologist, ethnographer, and folklorist who studied at Barnard College under legendary anthropologist Franz Boas at Columbia University, who assigned her the task of interviewing Cudjo Lewis (Kossola) for the Journal of Negro History. But Hurston was best known to the public in the 1930s, 40s, and 50s as an author. She wrote numerous novels, short stories, and works of poetry as well as nonfiction and an autobiography.

For further reading

Be sure to check out:

- Homegoing by Yaa Gyasi (African Roots through African eyes)

- Good books about racism

- Top 20 popular books for understanding American history

- Top 10 great popular novels reviewed on this site

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.

Wow! I hope our library carries this book. Coincidentally, I just watched an episode of “Finding Your Roots” on PBS, which mentioned this very ship. Questlove’s ancestors can be traced back to it as well. I wonder if he knows about this book? https://www.pbs.org/video/slave-trade-x7jpaa/

BPL has copies available now… just put one on hold. Thanks for the recommendation!