For most readers with a passing interest in espionage, the operations of the CIA beginning in the 1950s are reasonably familiar. But that’s not the case of the Agency’s work in the years immediately following World War II. Scott Anderson corrects that gap in The Quiet Americans, an illuminating account of four veterans of the wartime OSS who rose to positions of prominence in the new agency that came into existence in 1947.

A focus on four remarkable men

The four do not include any of the four OSS officers who later became directors of the agency. Allen Dulles and Richard Helms figure in Anderson’s reporting in supporting roles. William Colby appears only as a source and William Casey is mentioned only in the notes and bibliography. Instead the focus is on two names that are familiar to many of us—Frank Wisner and Edward Lansdale—and two who are not: Peter Sichel and Michael Burke. It’s a fascinating account of four men who helped the Truman and Eisenhower Administrations set the nation on the fateful and misguided course for which we are still paying the price.

The Quiet Americans: Four CIA Spies at the Dawn of the Cold War by Scott Anderson (2020) 702 pages ★★★★★

The four “quiet Americans”

In capsule biographies scattered through the pages of his book, Anderson traces the early lives of the four CIA spies, with emphasis on their service in the OSS in World War II and into the 1950s. Some of what he writes is familiar territory, as the story of the OSS is well known. But much else is available to a general reader only through the biographies and memoirs written by and about three of them and both official and academic studies of US foreign policy in the period.

Frank Wisner

Frank Wisner (1909-65) helped found the Central Intelligence Agency and played a pivotal role in its operations throughout the 1950s. As Anderson explains, Wisner had been widely expected to be Dwight Eisenhower’s choice as Director of the Agency instead of Allen Dulles. But J. Edgar Hoover‘s backroom manipulation and hostility—to him personally and to the CIA—denied him the job. He served as Deputy Director of Plans (DDP) until September 1958, heading up the Agency’s covert operations around the world. (It was the number two, and later number three, position in the CIA.) In 1958, however, he experienced a mental breakdown. He retired from the Agency four years later and committed suicide in 1965, despondent that so many of the foreign interventions he’d engineered had gone so badly awry.

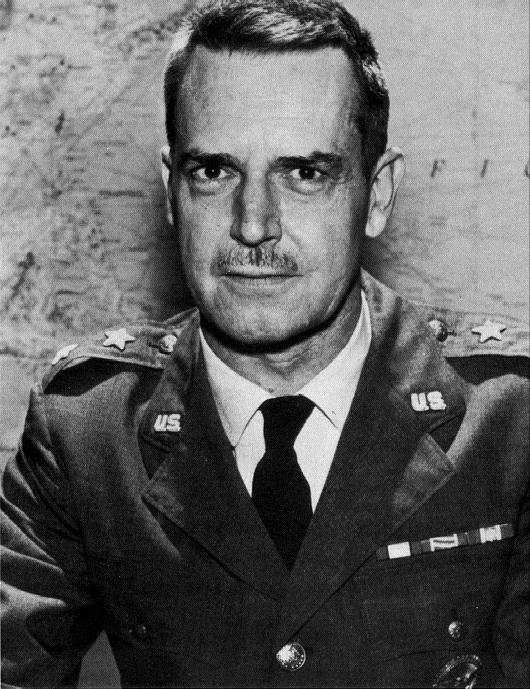

Edward Lansdale

An officer in the US Air Force who later worked for the CIA, Edward Lansdale (1908-87) gained fame in the early 1950s for his collaboration with Philippine President Ramon Magsaysay in crushing the Huk insurgency. It was during that experience that Lansdale pioneered the techniques of counterinsurgency and psychological warfare that he later brought to bear in South Viernam with Vietnamese President Ngo Dinh Diem.

As Anderson sees him, Lansdale was “one of the most celebrated and influential military intelligence figures of the coming Cold War, a theorist who painstakingly studied and then sought to emulate the enemy. So vast was his impact that he would serve as the thinly disguised protagonist of one best-selling book, The Ugly American, and quite possibly of a second, The Quiet American.” And a CIA director later named him as one of the ten greatest spies in modern history. He retired from the air force in 1963 as a major general but continued working thereafter with the CIA.

Peter Sichel

Peter Sichel was born in 1922 in Mainz, Germany, and is thus now nearly 100 years old as I write. To wine lovers throughout Europe and North America, he is known as a wine merchant, having rebuilt the family’s German business in the United States. But for nearly two decades earlier in life he worked, first, for the OSS during World War II, and later for its successors and the CIA. In the Agency, he was responsible for overseeing sabotage and intelligence missions behind the Iron Curtain, sending detachments of exiles behind the lines to disrupt Communist governments in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union. The majority of them were caught, and most were killed, sometimes immediately upon folding up their parachutes. The bitter experience of attempting without success to persuade his superiors to stop these suicidal missions led him eventually to resign from the CIA in 1960.

Michael Burke

Few people of any era can top the storied career of Michael Burke (1916-87). As Wikipedia notes, he “was a U.S. Navy Officer, O.S.S. agent, C.I.A. agent, general manager of Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus, CBS executive, President of the New York Yankees, the New York Knicks, and Madison Square Garden.” New Yorkers in the 1960s and 70s knew him as a curse to their beloved sports teams, which invariably chalked up badly losing seasons under his management. In the OSS and the CIA, by contrast, he was brilliantly successful as an operative in the field. Burke worked behind German lines with the French Resistance and later organized and managed many of the missions behind the Iron Curtain that so disturbed his boss, Peter Sichel.

Anderson’s verdict about the four

Of these four men, “[t]wo would leave the CIA in despair, stricken by the moral compromises they had been asked to make, or by their role in causing the deaths of others. Another, battling mental illness and haunted by a Cold War calamity he had tried to avert, would end up taking his own life. The fourth would make a kind of Faustian bargain, embracing governmental policies he knew to be futile in order to maintain his seat at the decision-making table, only to become a scapegoat when those policies failed.”

Six overarching themes

Six themes dominate Anderson’s account in this eye-opening book. The CIA was deeply involved in all six:

- The step-by-step buildup toward the Cold War, which might well have become a hot war very quickly after World War II. In fact there were those on both sides who seemed to wish it to happen. And the American military leadership was convinced it would.

- How the US stumbled its way into what became the Vietnam War, beginning with modest support for the French, who were struggling to hold on in Indochina, and steadily increasing as the 1950s turned into the 1960s.

- The emergence of what was later called Mutually Assured Destruction under Dwight Eisenhower in what Secretary of State John Foster Dulles called his New Look foreign policy.

- The tragically misguided policy of the Eisenhower Administration to overthrow foreign governments who threatened US commercial interests and, in too many cases, assassinating their leaders. The principal examples of this policy are well known: Iran (1953), Guatemala (1954), Congo (1960), and Cuba (1962), when the Bay of Pigs invasion took place. There were many others.

- The twin spectacles of the Red Scare and the Lavender Scare of the 1950s, fueled by FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover’s fury at being denied the leadership of the nation’s foreign intelligence operations when the CIA was launched. Hoover’s determination to wreak revenge on the CIA and the State Department led him to feed FBI files on “subversives” to Senator Joseph McCarthy, the useful idiot in his scheme.

- How Edward Lansdale pioneered America’s counterinsurgency strategy, first in leading the fight with Congressman and later President Ramon Magsaysay in the Philippines against the Huk guerrillas, and then (against his wishes) in guiding Vietnamese President Ngo Dinh Diem in his resistance to the North Vietnamese Army and the Viet Cong.

Two consequential insights

What may be the most consequential of the insights Anderson offers in this book regards the Eisenhower Administration’s dismissive response to overtures for peace almost immediately after the death of Stalin. “[B]y deriding the concept of ‘peaceful coexistence’ in favor of a continued policy of confrontation, they undercut the moderate faction within the Kremlin and bolstered the militants. In the estimation of President Eisenhower’s ambassador to the Soviet Union at the time, Charles Bohlen, by misplaying the aftermath of Stalin’s death in 1953, the United States may have missed a golden opportunity to dramatically alter the course of the Cold War.” And we paid for that miscalculation with the more than three decades of costly belligerence that followed.

Anderson also upends the popular view that the CIA drove foreign policy, not just under Dwight Eisenhower but in the decades that followed as well. “Far from being the ‘rogue elephant’ of Frank Church’s imagination,” he writes, “virtually every major covert mission undertaken by the CIA from its inception until today—from the overthrow of Iran’s Mossadegh, to the plots to kill Fidel Castro; from interfering in elections in Italy, to building a mercenary army in Laos; from secretly funding the Nicaraguan contras, to ‘proving’ Saddam Hussein possessed weapons of mass destruction—has been done under the express, if unwritten, orders of presidents. In adherence to the doctrine of plausible deniability, the CIA always has been—and likely always will be—the ultimate fall guy.” And the four CIA spies profiled in this book ended, in the final analysis, becoming fall guys themselves.

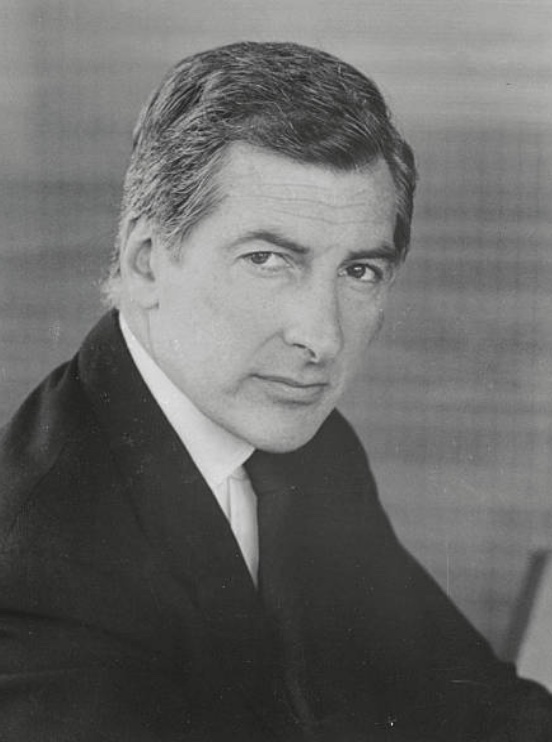

About the author

Scott Anderson (1959-) has written seven nonfiction books, two of them coauthored with his big brother, Jon Lee Anderson, and two novels. His best-known work is the biography, Lawrence in Arabia. He was raised in East Asia, primarily Taiwan and Korea, where his father was stationed as an agricultural advisor for the US government. He currently lives in Brooklyn, New York.

For related reading

I’ve also reviewed the author’s Lawrence in Arabia: War, Deceit, Imperial Folly and the Making of the Modern Middle East (Was Lawrence of Arabia the man you thought he was?).

Edward Landsdale, one of the four CIA officers profiled in this book, is widely cited as the model for the titular character in The Quiet American by Graham Greene (The classic Vietnam novel). And Lansdale is one of the central figures in The CIA: An Imperial History by Hugh Wilford (The CIA and American Empire).

For more insight into the Dulles brothers, see The Devil’s Chessboard: Allen Dulles, the CIA, and the Rise of America’s Secret Government by David Talbot (When America’s secret government ran amok) and The Brothers: John Foster Dulles, Allen Dulles, and Their Secret World War by Stephen Kinzer (They shaped US foreign policy for decades to come).

For perspective on the broader themes in the book, check out:

- 30 good nonfiction books about espionage

- Top nonfiction national security books

- 20 top nonfiction books about history

- 10 great biographies

- Understanding American history: a reading list

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.