Follow the news about the high-tech industry, and you’ll likely come across apocalyptic warnings that China is about to overtake the US in just about every field that matters, from artificial intelligence to semiconductors. What a relief it is, then, to read Chip War, a sober, up-to-date survey of the semiconductor industry by historian Chris Miller. With a sharp focus on the innovators and brilliant managers who brought computer chips into the mainstream of technology, the book traces the industry’s history from its origins in Texas and California in the 1950s. Miller dissects the successive threats to American dominance in the field from the USSR, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and, finally, the People’s Republic of China. The historical context matters, and Miller’s Big Picture perspective is reassuring—up to a point.

Estimated reading time: 7 minutes

As propulsive a reading experience as any thriller

Chip War consists of fifty-six chapters, including an introduction and a conclusion. They’re spread over 352 pages of text, averaging a little more than six pages each. And the scene shifts from one chapter to the next, helping move Miller’s story at a blistering pace more familiar to readers of thrillers than nonfiction. Often as not, a new chapter will introduce one of the fascinating characters who have played pivotal roles in the emergence of the semiconductor industry at the pinnacle of the world’s economy.

Chip War: The Fight for the World’s Most Critical Technology by Chris Miller (2022) 464 pages ★★★★★

A vitally important story peopled by amazing characters

The extraordinary characters who populate Chip Wars include:

- A prescient Soviet Minister of Defense who foretold the collapse of the USSR years before the West noticed the rot in the Communist system

- The Hungarian Jewish refugee from Nazi and Soviet armies who built the world’s most prominent semiconductor company with an obsessive passion for efficiency

- A scientific genius who won two Nobel Prizes and launched the computer chip industry, alienating everyone who ever worked for him

- The trader in dried fish who built one of the world’s largest tech companies—one of two surviving firms that fabricate most of the world’s most advanced microprocessors

- The mainland-born Chinese-American executive who left Texas to build the world’s largest semiconductor fab in Taiwan, known today as “the beating heart of the digital world”

Why chips are so important

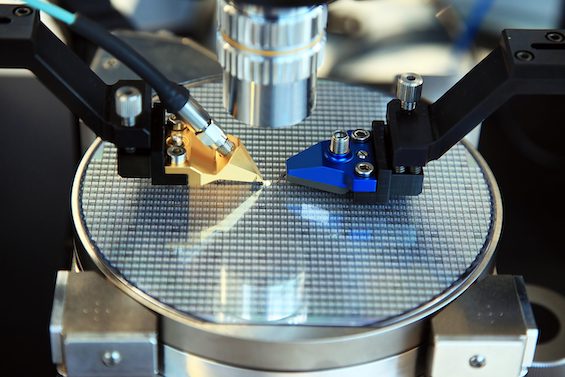

In Chip War, Chris Miller compares semiconductors to oil in terms of their importance to the world’s economy—and oil lands in second place. The Semiconductor Industry Association explains: “Semiconductors [also sometimes called integrated circuits or microchips] are an essential component of electronic devices, enabling advances in communications, computing, healthcare, military systems, transportation, clean energy, and countless other applications. . . Due to their role in the fabrication of electronic devices, semiconductors are an important part of our lives. Imagine life without electronic devices. There would be no smartphones, radios, TVs, computers, video games, or advanced medical diagnostic equipment.”

Few Americans appreciate just how central a role chips now play in our economy and our lives. That may be the result, at least in part, of the industry’s astonishing pace of development. As Miller observes, “It was only sixty years ago that the number of transistors on a cutting-edge chip wasn’t 11.8 billion, but 4.” In fact, as of 2022, the highest number had risen to 80 billion. Blame it on Moore’s Law, if you will—the prediction in 1965 by Gordon Moore, a cofounder of Intel, “that the number of transistors on a microchip doubles every two years.” To almost everyone’s astonishment, including Moore’s own, the law has proven largely true over six decades.

A US stranglehold on the “choke points” in chip design and production

“The United States still has a stranglehold on the silicon chips that gave Silicon Valley its name, though its position has weakened dangerously,” Miller writes. “China now spends more money each year importing chips than it spends on oil.” As the author explains, “Unlike oil, which can be bought from many countries, our production of computing power depends fundamentally on a series of choke points: tools, chemicals, and software that often are produced by a handful of companies—and sometimes only by one. No other facet of the economy is so dependent on so few firms.” And the US, sometimes through its allies, controls those choke points. The supply chains in the chip industry are Asia-centric, with plants in Taiwan and South Korea by far the most significant. But that is changing.

Recent news illustrates the point. The world’s largest semiconductor production company is TSMC, the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company. Along with Korea-based Samsung, which is smaller, it’s one of just two companies in the world that can manufacture the most cutting-edge processors. For decades, TSMC had resisted pleas to build advanced chipmaking facilities away from Taiwan, where it is vulnerable to a major earthquake or a potential invasion from the mainland. But on December 6, 2022, the company announced an investment of $40 billion in upgrading its plant outside Phoenix, Arizona, to produce enough chips to meet the entire US demand.

China’s challenge

As CNBC notes, “The [TSMC] announcement comes in wake of the passage of the CHIPS and Science Act which was signed into law in early August.” The US is fighting back. But regaining American hegemony in the industry doesn’t seem to be in the cards. “By 2030,” Miller explains, “China’s chip industry might rival Silicon Valley for influence.” For decades now, China has been using every means at its disposal to undermine America’s domination of the industry. Massive government subsidies. Industrial espionage. And commercial deals with IBM and other US-based companies, which are forced to trade intellectual property for access to the Chinese market.

For the US, the dilemma is straightforward. The entire chip industry depends on sales to China. Miller quotes a White House official’s explanation: “‘Our fundamental problem is that our number one customer is our number one competitor.'”

About the author

Chris Miller is Associate Professor of International History at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University, Jeane Kirkpatrick Visiting Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, and Eurasia Director at the Foreign Policy Research Institute. He also writes on his author website, “My historical research examines key shifts in international politics and economics. I’ve explored these topics in four different book projects.”

Miller’s first three books examined why the Soviet Union failed to adopt a system of Communist Party-controlled capitalism while China did; explored the state capitalism that emerged in Russia in the early 2000s, examining how it has proven so durable despite repeated external shocks; and asked why since the time of the tsars to the present day Russia has repeatedly sought geopolitical gains in Asia. “In addition to these books,” he adds, “I’ve also published multiple scholarly articles on Russian economic policy and intellectual history and on Russian-Chinese relations.”

For more reading

For an insightful and important book about another aspect of the competition between the US and China in technology, see AI Superpowers: China, Silicon Valley, and the New World Order by Kai-Fu Lee (The best book about artificial intelligence I’ve read so far).

You might also be interested in:

- 5 best books about Silicon Valley

- 30 insightful books about China reviewed on this site

- Gaining a global perspective on the world around us

- Science explained in 10 excellent popular books

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, plus a guide to this whole site, on the Home Page.