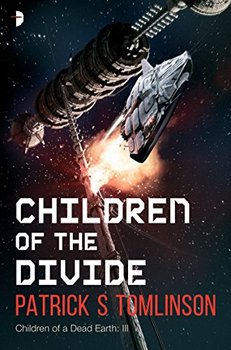

Eighteen years ago, the Ark arrived at Gaia, an Earth-like planet circling the star Tau Ceti. The 30,000 humans who survived the 235-year journey from the dying Earth have established the town of Shambhala on Gaia’s surface. They’re an ocean away from the network of villages and roads where the native inhabitants live on the continent of Atlantis. But now, in addition to the 30,000 humans who live in Shambhala, a young, fast-growing population of Atlantians lives in the “native quarter.” The brewing conflict between species is the setup in the third volume in Patrick S. Tomlinson‘s suspenseful sci-fi mystery series, Children of the Divide.

The people who drive the story

Although the cast of characters is satisfyingly broad, the novel revolves around three principal figures.

- Bryan Benson returns following his adventures in the two earlier books in the trilogy. Now fifty-two years of age, he’s the former Chief Constable of the Ark. He’s humanity’s hero for foiling the terrorist plot that threatened to extinguish Earth’s survivors. His wife, Theresa, is now Constable herself. Together, they’re the adoptive parents of a fifteen-year-old Atlantian child named Benexx. There’s no conflict between species in their family. Benexx is a teenager, and they’re the parents.

- Like human teenagers, Benexx is cranky and rebellious. Ze—the Atlantians’ personal pronouns are ze/zer/zers—regards Bryan as an unreasonable old fossil. Zer kidnapping triggers one of the principal arcs of the story.

- Meanwhile, an equally prominent storyline unfolds far above the surface of Gaia. Twenty-five-year-old Jian Feng, son of the Ark‘s captain, Chao Feng, is Benexx’s best friend. He was newly promoted within the Ark‘s crew and now commands one of the shuttles. On assignment, he leads a team to Gaia’s moon. There, he uncovers an ancient, high-tech installation placed there by yet a third intelligent species unknown to the humans.

Other characters play meaningful roles in the story, many of them holdovers from the earlier books, including Captain Chao Feng and the Atlantian “truth-digger” (detective), Kexx. There’s also an adorable, shapeshifting little automaton that Tomlinson characterizes as a “bionic bug.” Oh, and there are terrorists here, too. Again.

Children of the Divide (Children of the Dead Earth #3) by Patrick S. Tomlinson (2017) 430 pages ★★★★☆

A tale of conflict between species—and collaboration, too

Children of the Divide is fundamentally a story about how two sentient races might interact. It’s also a tale of fathers and the difficult relationships they have with their children. But above all, perhaps, it’s a product of a novelist’s wishful thinking about the abundance of extraterrestrial life.

Given the Great Silence, it seems appropriate to assume that, at the very least, life is rare in the universe. Of course, there are hundreds of billions of galaxies, each of which contains hundreds of billions of stars, so even though rare, life might indeed exist on thousands or even millions of worlds. The problem is, distances in the universe are so unfathomably great that the possibility for humans to encounter another sentient species within twelve light-years—Tau Ceti’s distance from Earth—is vanishingly small.

How accurate is the science in this science fiction novel?

The best answer to this question is, it depends. Tomlinson puts on a good show of demonstrating that he understands perfectly well what space travel might be like and how people would cope with weightlessness and varying levels of gravity. He goes into credible detail about how engineering problems might be solved. And he successfully inserts such technical terms as “van der Waals’ forces,” “orbital insertion,” and “Kardashev Type II civilization” in his text. (Look them up, if you’re wondering.) On the surface, Children of the Divide comes across as hard science fiction. But it’s not.

The two sapient species are unlikely to be so similar

The people who populate the town of Shambhala and the Ark in the skies above are recognizably human. But the native Atlantians are like them in far too many ways to be believed. They’re bipedal, they speak words aloud, they build towns, and they fight battles with weapons that resemble those of fourteenth century Europe. They even share a sense of humor with the colonists! None of this seems likely, given the vast, even inconceivably wide range of possible body shapes and means of communication that life might otherwise have selected. However, the conflict between species seems understated, if anything.

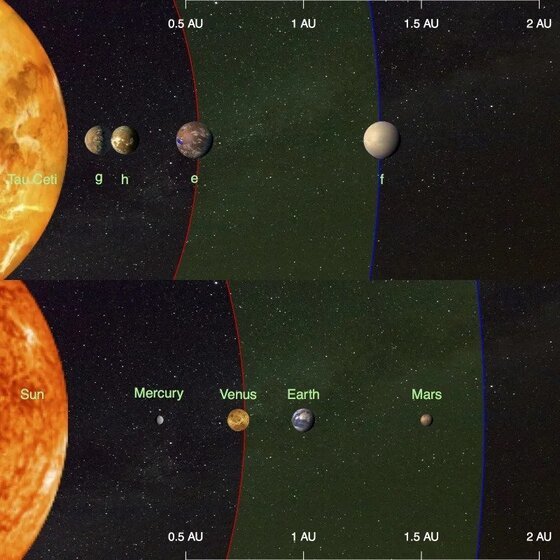

What the new planet is actually like

The planet Tomlinson’s colonists have named Gaia is Tau Ceti g, the innermost of the four “Earth-like” planets discovered orbiting our closest sun-like star. While it’s possible that Tau Ceti e or f could in some way actually resemble Earth—they orbit their primary at distances of 0.5 AU and about 1.3 AU (about 46 million or 121 million miles, compared to Earth’s 93 million—but they’re both about four times as massive as Earth, so the gravity would be punishing for humans. But the planet called Gaia in this novel couldn’t conceivably be anything like Tomlinson says it is. It’s situated extremely close to Tau Ceti, with an orbital radius of 0.13 AU, or about 12 million miles compared to Earth’s 93 million.

The colonists in this novel couldn’t survive on Gaia

In other words, it seems impossible that anything but extremophile life could exist on Gaia because it would be instantly snuffed out by the torrential radiation from the star. That’s if the searing heat didn’t get them instead. (On Mercury, which is five times as far from Sol as Tau Ceti g is from its primary, the surface temperature reaches 800 degrees.) And Gaia circles Tau Ceti every 20 days, which would disorient colonists, to say the least.

The verdict

Children of the Divide is a flawed piece of work, and not just because the planetary science doesn’t hold up or the conflict between species seems too tame. The book abounds with anachronistic figures of speech (“roger that”) and cultural references (“like a famous coyote,” referring to the cartoon figure of Wile E. Coyote). And there are far too many malapropisms (“on the lamb” for “on the lam”) and other abuse of the language. Typographical errors, misspellings (“non-neutonian fluid, with “u” for “w”), and errors in word usage (“too ubiquitous” for just “ubiquitous”) are frequent, too. But it’s still a good story.

Its flaws notwithstanding, Children of the Divide is well-crafted and consistently entertaining. It works both as a mystery and as science fiction. The dialogue is crisp and occasionally amusing. (Tomlinson is a standup comic as well as a writer.) I recommend the book, but I suspect readers would find it most rewarding to begin with The Ark, the first of the three books that have appeared to date in this series.

For further reading

I’ve previously reviewed the first two books in the Children of the Dead Earth series:

- The Ark (On a starship, an art heist, a murder, a coverup)

- Trident’s Forge (A suspenseful mash-up of science fiction and mystery)

For more good reading, check out:

- The ultimate guide to the all-time best science fiction novels;

- Great sci-fi novels reviewed: my top 10 (plus 100 runners-up);

- Seven new science fiction authors worth reading; and

- The top 10 dystopian novels reviewed here (plus dozens of others).

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, plus a guide to this whole site, on the Home Page.