To say that Annalee Newitz’s interests are eclectic grossly understates the point. They—Newitz’s personal pronouns are they/their/theirs—are the author of two science fiction novels and two works of nonfiction that sprawl across a broad swath of issues and preoccupations. Newitz has also edited or co-edited a number of other nonfiction books and contributed chapters to several more. And a third novel is scheduled for publication later this year. The subjects of these works include mass extinction, race and class in America, popular culture, robots, and alternate feminist history, among many others. In Four Lost Cities, their latest outing into the realm of the printed word, they venture into urban history through the lens of archaeology. With Annalee Newitz as your guide, you’ll join archaeologists at work in some of the most fascinating spots around the world.

Four Lost Cities: A Secret History of the Urban Age by Annalee Newitz (2021) 309 pages ★★★★★

A wide-angle portrait of archaeologists at work

This book is, above all, a wide-angle portrait of archaeologists at work. Over the course of seven years, including many summers spent at dig sites across the world, Newitz interviewed scores of archaeologists. The picture that emerges is likely to revise the impression most of us have had of what archaeologists actually do.

Of course, few take seriously the mythical figure of Indiana Jones as representative of the field. But the far more sober picture of archaeologists on their knees in godforsaken places, sifting through the earth for pottery shards and ancient weapons isn’t much closer to the truth. (OK, it’s a big part of the picture.) Today, archaeologists employ science in manifold ways to suss out the story of the past.

How science and technology have revolutionized archaeology

Contemporary science and technology come into play in several ways in the pages of Four Lost Cities.

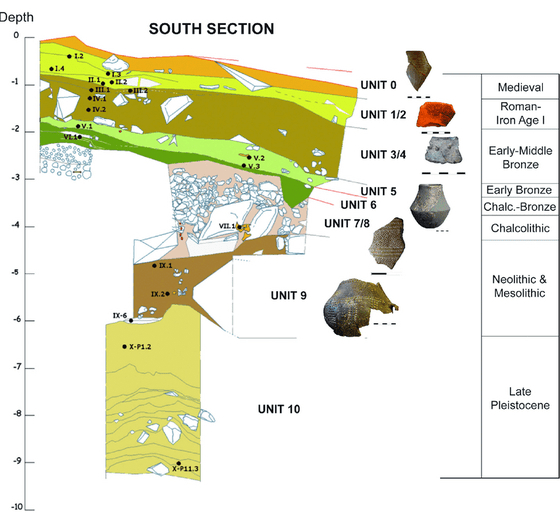

Stratigraphic mapping

To distinguish among the layers beneath a settlement built atop a series of earlier communities, archaeologists employ stratigraphic mapping analogous to the method used to distinguish one geological epoch from another.

Computational archaeology

In data archaeology, or computational archaeology, investigators study long-term human behavior and behavioral evolution by discerning patterns in the data sets that emerge from close observation of the tiny details in a dig. For example, they may count the number of times they find pottery produced elsewhere versus pottery produced at the site they’re studying. The might suggest the importance of trade to the inhabitants.

Lidar

With lidar (Light Detection And Ranging), specialists can probe the location, depth, and dimensions of structures long buried under the earth, even in the midst of a forest or jungle.

Newitz’s description of these methods merely hints at the sophistication of the science brought to bear by archaeologists at work today. Dig deeper into the field, and you’ll find a bewildering array of other scientific methods that now figure in this increasingly demanding discipline. Radiocarbon dating is only the most familiar of these techniques.

The four “lost cities”

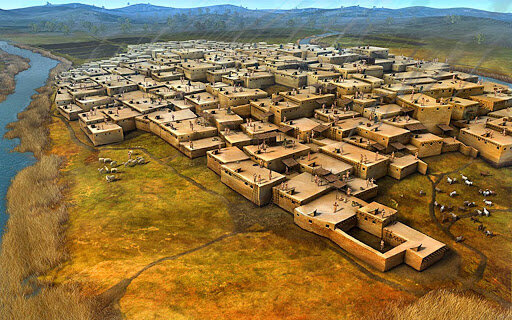

Çatalhöyük

Located in present-day south-central Turkey, Çatalhöyük was a Neolithic (Stone Age) community that flourished from approximately 7100 BCE to 5700 BCE. At its peak, the city’s population is estimated to have reached 10,000 at most. Many of its inhabitants “were only a generation or two removed from nomadism.” Thus, it may be misleading to characterize the place as a city. Elsewhere, Newitz refers to it as a “Neolithic mega-village.” Çatalhöyük predated the age of empires; “there were no kings or big bosses.” Like most of the other cities Newitz studied, Çatalhöyük is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The site was first excavated in 1958 by James Mellaart, who did his work in the 1950s and 60s and is not among among the many working archaeologists Newitz interviewed for this book. They take him to task for his thesis of “goddess worship,” a discredited analysis of Çatalhöyük’s belief system. Newitz’s emphasis, like that of a great many of the scientists they spoke with, was on daily life in the city and on analyzing why and how Çatalhöyük could have become “lost.” But even when most of the city’s inhabitants had moved on to other, smaller cities or back to village life, “nobody ‘lost’ the city . . . The place remained special, long after people left it.” For archaeologists at work today, Çatalhöyük is most interesting for the light it shines on the rise and fall of cities.

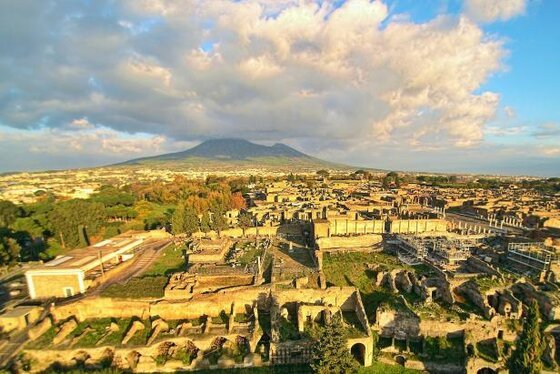

Pompeii

It’s well known that in 79 CE the volcano Vesuvius erupted violently, burying the Roman resort town of Pompeii and several neighboring communities under up to six meters of burning ash. Largely preserved under the ash, the excavated city offered a unique snapshot of Roman life, frozen at the moment it was buried. But, in Newitz’s telling, what we have learned about Pompeii was not truly representative of Roman lifestyles.

Like other communities in the empire, the city, home to an estimated 12,000 people, was specialized. Pompeii was a resort and trading center. It was “a diverse urban community, whose population came from many places, and fused the traditions of of North Africa and Rome into something that was uniquely Pompeii.” It was also wealthy and offered an unusual number of large villas. Some were owned by Romans who summered there to escape the greater heat of the capital, others by those who did business in the bustling nearby warehouse town and port of Puteoli (Pozzuoli today).

Newitz writes in fascinating detail about slavery in Pompeii. This was not the chattel slavery experienced by Africans dragged to the Americas but something more closely akin to indentured servitude like that which brought so many settlers to the American colonies. “The typical Roman household,” Newitz notes, “would have been roughly half slaves, and a quarter to a third liberti [ex-slaves]. Up to three-quarters of free people in cities were either ex-slaves or their descendants.”

Angkor Wat

Angkor Wat is a twelfth century temple complex in Cambodia and the largest religious monument in the world by land area, comparable in size to Los Angeles, but it was also a populous city. According to Oliver Wainwright in The Guardian, “At its peak in the 12th century, when London had a population of 18,000, Angkor was home to hundreds of thousands, some estimate up to three-quarters of a million people. . . [but] it was the prototype of modern-day suburban sprawl.” There was no central city.

Newitz goes further. “Eleven hundred years ago,” they write, “Angkor was one of the biggest metropolises in the world, thronging with nearly a million residents, tourists, and pilgrims.” It was the capital of the vast Khmer Empire, which subjugated most of present-day Cambodia, Laos, Thailand, and Vietnam and parts of Southern China. Unlike most accounts of Angkor Wat, Newitz avoids a detailed description of the striking architecture and dwells instead on the lives of the inhabitants.

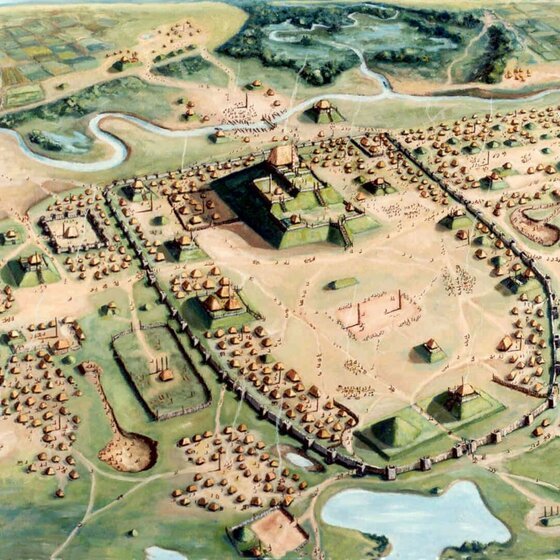

Cahokia

Even today, most Americans labor under the illusion that the native peoples Europeans encountered here in the fifteenth, sixteenth, and seventeenth centuries lived exclusively in tiny settlements, if they had settled anywhere at all. But history tells us that, in what is today upstate New York and surrounding states, the Iroquois Federation had achieved a level of sophistication in the organization of its communities and in its government that helped inspire the writing of the United States Constitution. And more than a thousand years before European contact, the city of Cahokia on the shore of the Mississippi River housed a population of over 30,000 people from the ninth through the fourteenth centuries—more than lived in London or Paris at the time.

It “was the largest city in North America before the arrival of Europeans,” and Newitz cites the conclusions of archaeologists who have devoted years to studying Cahokia that the city’s purpose was ceremonial rather than economic. “It was a spiritual center rather than a trade center,” they write.

Is there any pattern to the rise and decline of these four cities Newitz studied? They think not. “By the 1970s,” they write, “archaeologists and urban historians had accumulated loads of evidence that urban civilizations have no set developmental pattern . . . [and] urban abandonment does not mean some kind of cultural death,” Jared Diamond’s bestseller, Collapse, notwithstanding. Diamond’s environmental determinism “leaves out the crucial political aspects of urban transformation. . . What he gets wrong is that the public is diverse and always changing.”

A multitude of other “lost cities”

In the course of more than ten millennia, thousands of cities have been founded on every one of the six inhabited continents on Earth. Many have long since passed into history, abandoned or destroyed for reasons that are often difficult to discover. Newitz might have picked a great many other examples in addition to the four she chose. Today, archaeologists are at work on many other sites around the world. Among the best known and potentially most interesting of those she avoided are four.

Great Zimbabwe

Great Zimbabwe, located in present-day Zimbabwe, is believed to have been the capital of a great kingdom during the Late Iron Age. Built in the eleventh century, it could have housed up to 18,000 people for several hundred years until it was abandoned in the fifteenth century.

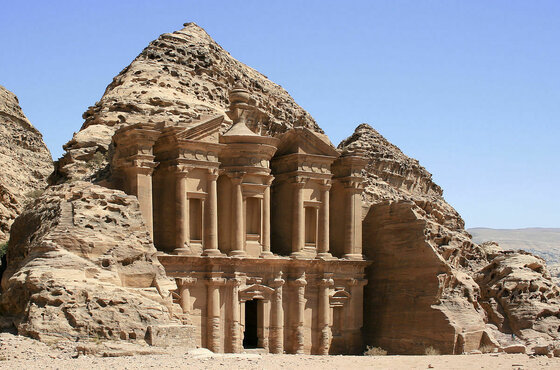

Petra

The ruins of Petra lie in southern Jordan, which has been inhabited since approximately 7,000 BCE. From the second century BCE through the first century CE, Petra served as the capital of a Nabataean kingdom with a population that peaked at an estimated 20,000 inhabitants.

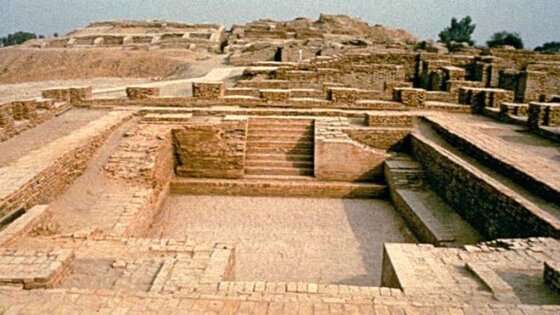

Mohenjo-daro and Harappa

Archaeologists believe that the Indus Valley Civilization centered in present-day Pakistan during the Bronze Age was contemporaneous with those in the Middle East and China, flourishing from 3300 BCE to 1300 BCE. Mohenjo-daro was one of its principal cities with a population estimated to contain between 30,000 and 60,000 individuals. (Harappa was a similarly large city nearby.) The cities anchored an area containing as many as five million people.

Xanadu

Xanadu, or Shangdu, was the summer capital of the Yuan dynasty of China that ruled the Mongol Empire, before Kublai Khan moved his throne to what is today Beijing. At its zenith, over 100,000 people lived within its walls. The city flourished for a century until conquered by a Ming army in 1369. Western accounts of the city inspired the famous poem Kubla Khan by the English Romantic poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge.

Newitz on “lost cities”

“The ‘lost city’ is a recurring trope in Western fantasies,” Newitz writes. But, as they amply demonstrate in the pages of this illuminating account, “modern metropolises are by no means destined to live forever, and historical evidence shows that people have chosen to abandon them repeatedly over the past eight thousand years, It’s terrifying to realize that most of humanity lives in places that are destined to die. The myth of the lost city obscures the reality of how people destroy their civilizations.”

Clearly, given how ineffectually we’re responding to the climate emergency and rising sea levels today, it would be naive for us to think that the future of cities is unrelievedly bright. “Eventually,” they argue, “some of today’s megacities will look like something out of a far-future science fiction movie, full of half-drowned metal skeletons covered in incomprehensible advertisements for products we can no longer afford to make or buy.”

About the author

Berkeley-based writer Annalee Newitz (born 1969) is a prolific author, editor, and columnist who divides their time between fiction and nonfiction. Their continuing roles include work as a contributing opinion writer at The New York Times, co-editor with their partner Charlie Jane Anders of the technology and science fiction website Gizmodo, and occasional appearances in the pages of such magazines as New Scientist, Wired, and Popular Science. They hold a Ph.D. in English and American Studies from UC Berkeley.

For related reading

For my reviews of two other books about lost cities, see The Lost City of the Monkey God by Douglas Preston (The true story of a lost city in Central America) and The Lost City of Z: A Tale of Deadly Obsession in the Amazon by David Grann (Pre-Columbian civilization in the Amazon).

I’ve also reviewed three other books by Annalee Newitz, two novels and two other works of nonfiction:

- Scatter, Adapt, and Remember: How Humans Will Survive a Mass Extinction (Will the human race survive climate change and a mass extinction?)

- Autonomous (In 2144, Arctic resorts, autonomous robots, and killer drugs)

- The Future of Another Timeline (Alternate feminist history by a gifted science fiction author)

- Stories Are Weapons: Psychological Warfare and the American Mind (Propaganda, conspiracy theories, and psyops in American history)

You might also be interested in:

- Against the Grain: A Deep History of the Earliest States (This book will challenge everything you know about ancient history)

- A History of Future Cities by Daniel Brook (Urbanization, globalization and the future of humanity)

- 20 top nonfiction books about history

- Science explained in 10 excellent popular books (plus dozens of others)

Annalee Newitz’s books are also listed at Good books by Berkeley authors.

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.

The leopard’s tale: revealing the mysteries of Çatalhöyük

Anthropologist describes the excavation of Çatalhöyük, a nine-thousand-year-old Neolithic mound in central Turkey. Pieces together the lives and culture of ancient village inhabitants from artifacts, many of which have leopard images. Discusses the impact of the archaeological finds on modern understanding of early farming and the development of agriculture. 2006.(BARD Express)

You didn’t mention this book.Ian Hodder has youtube videos, too.

Thanks. I didn’t mention it because I hadn’t read it.