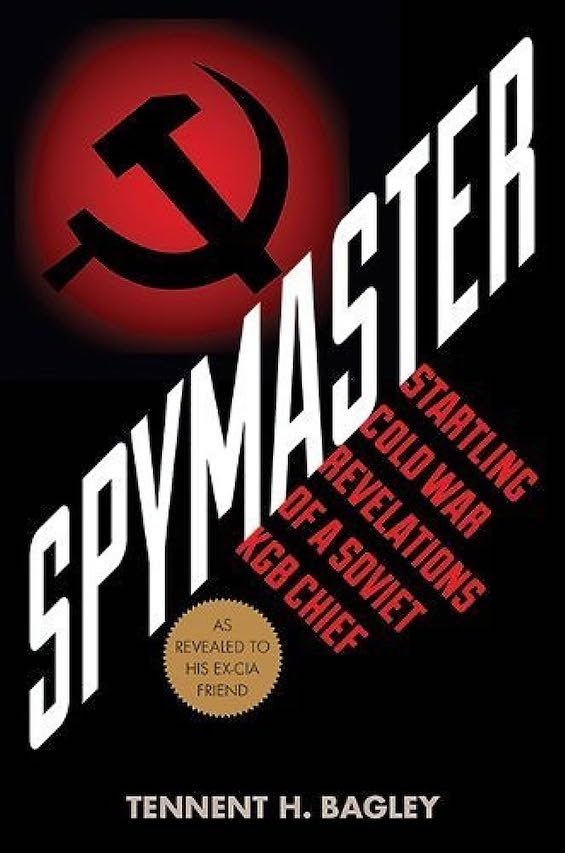

Thousands of books and millions of words have been written about the tit-for-tat battle of the KGB and the CIA during the more than four decades of the Cold War. Some factual accounts and a smattering of novels offer genuine perspective on the two spy agencies and their interaction. But only rarely, if ever, has a book appeared that digs so deeply into the many mysteries surrounding Soviet intelligence activities as Spymaster by Tennent H. Bagley. Based on the autobiography of a top KGB spymaster, the book is tantamount to a guidebook on the ways and means of the KGB in its ongoing effort to counter the West. In a foreword, investigative journalist and Harvard political science professor Edward J. Epstein calls it “the single most important book about espionage to emerge from the Cold War.” It’s easy to see why.

How this book came to be written

Author Tennent H. “Pete” Bagley was a 24-year veteran of the CIA. Having joined in 1950, just three years after its founding, he was a rising star in the agency. For years he served as chief of counterintelligence in the Soviet division, where he interrogated a succession of high-level KGB defectors. But Lieutenant General Sergey Aleksandrovich Kondrashev (1923-2007), the subject of this book, was not one of them. He served the KGB loyally from 1944 to 1992. And Bagley and Kondrashev never met while they worked at cross-purposes in their respective agencies.

In 1994, 20 years after Bagley had retired from the CIA, the two men got together to reminisce. And that led Kondrashev to ask Bagley for help in writing his autobiography. After seven years of work, they completed the Russian edition shortly before Kondrashev’s death in 2007, and he submitted it for clearance to the KGB’s successor agency, the FSB—which suppressed it. Bagley later took the manuscript as the basis for his own book, including sections verbatim as dictated by Kondrashev—and weaving in passages the KGB spymaster had told him were off the record. And he folded in commentary from his own personal experience, often involving operations Kondrashev had initiated.

Spymaster: Startling Cold War Revelations of a Soviet KGB Chief by Tennent H. Bagley (2013) 320 pages ★★★★★

Startling revelations from a top KGB spymaster

Spymaster‘s subtitle promises “startling revelations,” and they are that for sure. Here are three among the many:

Khrushchev and Kennedy

Kondrashev revealed to Bagley what Nikita Khrushchev really thought of JFK. Press accounts, including that on PBS, reported at the time that the Soviet Premier “thought of him as young, weak, ineffective, and probably a pushover.” Not so, Kondrashev insisted. And he knew from direct experience, since Khrushchev personally told him he was impressed by the younger man. During his long KGB career, Kondrashev dealt face-to-face with a succession of top Soviet leaders, from Stalin to Khrushchev to Brezhnev to Andropov.

The spy tunnel

One of the most widely told stories of the Cold War was the saga of the British-American spy tunnel in Berlin. In 1954, they’d dug a tunnel to tap the phone lines outgoing from Soviet Army headquarters. It ran for eleven months until the Soviets stumbled across it in a routine security check—or so it was long believed. But Kondrashev told the true story. The KGB had known about the tunnel from the time of its planning from George Blake, a high-level British intelligence officer who later defected to Moscow. The Russians let the tunnel operate unmolested for a total of a year and a half (including its construction time) to protect their source.

Recruiting Nazis

It’s well known that American Army Counterintelligence protected Klaus Barbie, the “Butcher of Lyon,” and used him as a source for a time. There were others, too. And some high-ranking Nazis later went to work for West German intelligence and the government in Bonn. “But,” Kondrashev revealed, “the KGB’s operation was on a different plane altogether. It used the highest-level and most wanted war criminals to enlist others of their ilk in a long-range pro-Nazi operation that made the KGB, in effect, their collaborators in preparing for a ‘Fourth Reich.'”

Among them was “Gestapo” Müller, who “had overseen mass murder, torture, and cruelty on a scale still hardly imaginable. He was arguably the least forgivable of all the war criminals, and he was also the most sought: He and Martin Bormann stood at the top of a postwar list of the Allies’ ‘most wanted.'” The KGB put them to work against the West Germans and the “main enemy,” the United States.

The Nosenko affair

Pete Bagley witnessed many of the operations Kondrashev described—from the perspective of the CIA, of course. But one preoccupied him for decades. Because the defining episode of Bagley’s life was his ongoing involvement in the controversy surrounding KGB officer Yuri Nosenko (1927-2008). He himself had been the CIA’s contact in Vienna in 1961 when Nosenko volunteered to spy for the agency. And he had spent months after Nosenko later defected interrogating him, sometimes subjecting the Russian to methods later observers would call (psychological) torture.

Nosenko proved to be an inveterate liar, and inconsistently so. His “self-contradictions, blundering improvisations, and blatant indifference to truth” convinced Bagley that Nosenko was a KGB plant. His purpose, Bagley knew, was to undermine the revelations of an earlier, authentic KGB defector named Anatoliy Golitsyn (1926-2008), who had insisted there were multiple moles in the CIA. But Bagley’s superiors in the agency refused to believe him.

And here’s how Bagley explains why they chose Nosenko’s lies over his insistence that the man was a Soviet plant. “[T]he CIA badly wanted to believe Nosenko’s messages. To disbelieve them and look behind them might bring to light ugly things no one wanted to see: undiscovered moles inside the agency or breaks of American ciphers that had enabled the Soviet Union to read America’s secret communications at critical periods of the Cold War.” And the powers that be in the agency sidelined Bagley to hide all this, and eventually they forced him out of the CIA and out of the country. He spent the last forty years of his life living in Brussels.

All this is documented in The Spy Who Knew Too Much: An Ex-CIA Officer’s Quest Through a Legacy of Betrayal by Howard Blum. And Kondrashev confirmed Bagley’s conclusions in every respect.

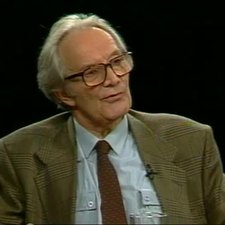

About the author

Tennent H. Bailey (1925-2014), known as “Pete,” was one of the CIA’s highest-ranking officers during the height of the Cold War in the 1960s and early 70s. The youngest of three boys in a prominent Navy family—both his father and his two older brothers became admirals—he joined the CIA in 1950 after service in World War II as a lieutenant in the Marines. He was educated at the University of Southern California and at the Graduate Institute of International Studies in Geneva, where he received a PhD in Political Science. Bagley stood out as a star at the agency from the outset, quickly moving up the ladder. Years later, former CIA director Richard Helms told a journalist that he had considered him a prime candidate to head the CIA.

A counterspy at the agency, he was best known for his work with the supposed KGB defector Yuri Nosenko. His insistence that Nosenko was in fact a mole collided with his superiors’ investment in the man. He left the CIA in 1974, the same year Director William Colby forced his colleague, James Jesus Angleton, to retire. Bagley wrote or coauthored three books on the CIA and the KGB. Spymaster was the last of them.

For related reading

This is one of The 21 best books of 2023 and it’s one of the top 10 nonfiction books that changed my thinking.

For a remarkable account of Pete Bagley’s decades-long investigation, see The Spy Who Knew Too Much: An Ex-CIA Officer’s Quest Through a Legacy of Betrayal by Howard Blum (Unmasking the mole in the CIA). And the controversial investigation into the bona fides of Yuri Nosenko is the subject of David Quammen’s superb 1987 novel, The Soul of Viktor Tronko (Digging down deep to find the mole in the CIA).

Two other books I’ve reviewed profile two of the recurring characters in Bagley’s account:

- An Impeccable Spy: Richard Sorge, Stalin’s Master Agent by Owen Matthews (The greatest spy of the twentieth century?)

- The Matchmaker: A Spy in Berlin by Paul Vidich (A dangerous spy game in Berlin before the fall of the Wall)

For Pete Bagley’s obituary in the Washington Post, see “Tennent H. ‘Pete’ Bagley, noted CIA officer, dies at 88” (February 24, 2014).

You might also enjoy my posts:

- The 15 best espionage novels

- Good nonfiction books about espionage

- The best spy novelists writing today

- Top 10 mystery and thriller series

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.