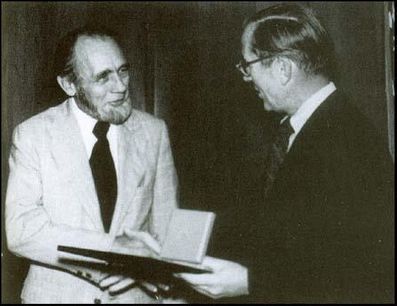

According to most expert observers of the intelligence community, James Jesus Angleton (1917-87) had long since descended into paranoia when he retired in 1974 after two decades as CIA chief of counterintelligence. During his last years in the service, Angleton had torn the agency apart in a futile search for a KGB mole. Under William Colby, who was Director from 1973 to 1976, the CIA closed ranks. It became anathema to claim that the KGB had ever penetrated the agency. But now, in The Spy Who Knew Too Much, popular historian Howard Blum makes a persuasive case that Angleton was right all along. In fact, he demonstrates, there was not one but at least two moles. And the nation’s security system suffered grievous losses as a result.

Estimated reading time: 6 minutes

Jim Angleton knew there was a mole

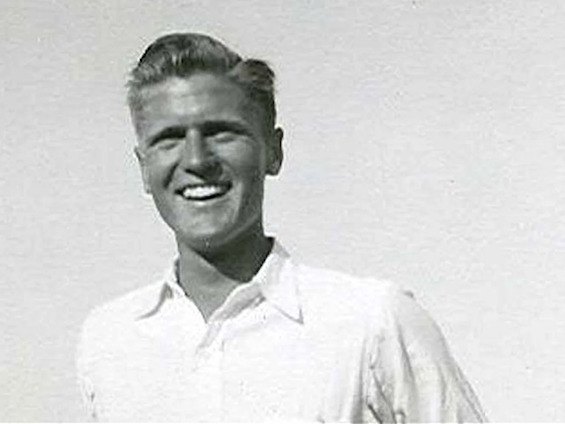

In “A note to the reader” at the outset, Blum writes that “my intention is to reveal one of the last great secrets of the Cold War. It is also the true story of one spy’s quest through a legacy of betrayals to solve this mystery.” That spy was Tennent “Pete” Bagley (1925-2014), whom Blum casts as the hero of his story. During decades of intensive digging through thousands of pages of obscure official documents, and in interviews with other intelligence officers at the KGB as well as the CIA, Bagley proved to Blum’s satisfaction—and mine—that the mysterious mole Angleton had pursued was a man named John Arthur Paisley (1920-78?).

The Spy Who Knew Too Much: An Ex-CIA Officer’s Quest Through a Legacy of Betrayal by Howard Blum (2022) 352 pages ★★★★★

A mole-hunter as devoted as Angleton himself

In fact, as Pete Bagley set out on his quest in 1978, he was already well aware of at least one long-time mole in the agency—a KGB “defector” named Yuri Nosenko who Bagley knew was not a defector at all. Bagley himself had made the agency’s first eye-to-eye contact with Nosenko in Vienna in 1964 and interrogated him for months, sometimes brutally. The enormous number of contradictions in the man’s story convinced him that the KGB had planted him to divert attention from a highly placed American who was the CIA mole Angleton was looking for. But Bagley’s superiors disagreed, and at length he was accused of paranoia, himself investigated as a mole, and discredited. The experience led him to remove himself from the drama in Langley and eventually to resign from the agency at the age of forty-six.

Two suicides who never killed themselves

Six years after his retirement from the CIA, Bagley was startled by an unlikely coincidence. “Two deaths—each purportedly a suicide, each with its deep roots in the secret world, each with its own perplexing mysteries” caught his attention in 1978. Bagley was living in Brussels after stepping down as CIA station chief there. One of the men who died was a KGB defector who had provided invaluable information to the agency. The other was a long-serving CIA senior officer. In both cases, the circumstances made it clear to Bagley that suicide was unlikely. And as he dug deeply into the available (and sometimes secret) facts, he became convinced that neither had killed himself.

An amateur detective with a sparkling resumé

Bagley brought to the task both an obsessive concern for the truth and a passionate commitment to serve his country. He was Navy through and through. “A small flotilla of warships, from frigates to cruisers, had been christened with the names of his father and uncles.” His two brothers each rose to the rank of four-star admiral. And his “Uncle Bill” was five-star Fleet Admiral William D. Leahy, who was the highest-ranking US military officer to serve in World War II and was both FDR and Harry Truman’s Chief of Staff.

Bagley himself was unable to follow his brothers at Annapolis because of his “dodgy eyesight.” His career in the CIA was distinguished, involving him in some of the agency’s biggest wins over the years. Colleagues believed he would some day become Director of the CIA. This was not a man to himself betray his county, as some in the CIA maintained.

Upending the history of the Cold War

Blum’s account of the course Bagley took in his decades-long investigation follows a serpentine course through the officer’s career and the history of the intelligence battles throughout the Cold War. Summarizing the story is a challenge beyond my capabilities. Suffice it to say that, step by step, Blum demonstrates how Bagley made the case the CIA was infiltrated for decades by at least two moles in the pay of the KGB. Naturally, bureaucracy—and especially espionage bureaucracy—being what it is, the CIA will never acknowledge the truth of Bagley’s findings. That’s understandable, since the events Bagley investigated happened so long ago. Unfortunately, it’s all but certain that most historians will buy the official line and distort a crucial chapter in the history of the Cold War.

About the author

Howard Blum is the author of fifteen nonfiction books, many of them about the history of espionage. He won the Edgar Award for one of his true crime books. Blum is a former reported for the Village Voice and the New York Times and is a contributing editor at Vanity Fair. He was born in New York City in 1948 and earned a bachelor’s degree and a master’s in government from Stanford University. He is divorced and now lives in New York and Connecticut.

For related reading

For confirmation of the story Howard Blum tells in this book, see Spymaster: Startling Cold War Revelations of a Soviet KGB Chiefby Tennent H. Bagley (Startling revelations from a top KGB spymaster).

I’ve also reviewed two other books by Howard Blum:

- Night of the Assassins: The Untold Story of Hitler’s Plot to Kill FDR, Churchill, and Stalin (The startling Nazi plot to kill FDR, Churchill, and Stalin)

- In the Enemy’s House: The Secret Saga of the FBI Agent and the Code Breaker Who Caught the Russian Spies (How the Soviet atomic spies were caught)

For a different perspective on this book, see “A Spy Story Too Juicy to Be True?” (Commentary, September 2022) by Harvey Klehr. If the CIA were to authorize a review of Blum’s book, this might be it. And for a fictional account that encompasses many of the facts revealed in this novel, see The Soul of Viktor Tronko by David Quammen (Digging down deep to find the mole in the CIA).

You might also care to check out:

- Good nonfiction books about espionage

- Good nonfiction books about national security reviewed here

- Top 20 popular books for understanding American history

- The 15 best espionage novels

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, plus a guide to this whole site, on the Home Page.