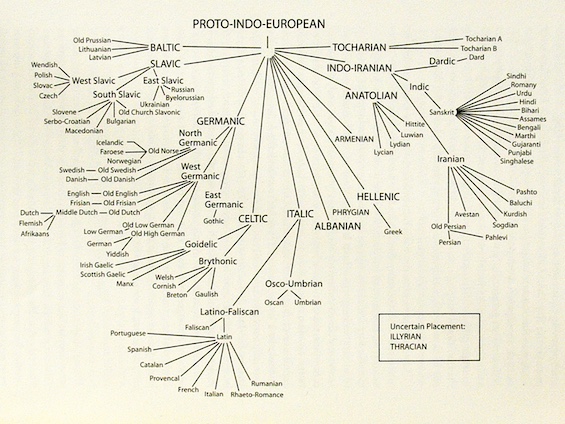

Chances are slim that you can read or understand spoken Russian, Swedish, or Hindi. But, believe it or not, English is related to all three languages—and more than 400 others. They’re all descendants of a single ancient language linguists call Proto-Indo-European. “Proto” was the language spoken by the semi-nomadic herders living on the grasslands in what is now Ukraine and southern Russia around 6,500 years ago (c. 4500 BCE). And the descendants of those Proto-speakers one or two thousand years later—the Yamnaya people—emigrated from their homeland and spread throughout Europe to the west and north. Along the way, Proto came under the influence of local tongues and evolved, as languages do. The result was the languages we recognize today. But that’s only half the story. Science journalist Laura Spinney explains in her fascinating account of language dynamics, Proto: How One Ancient Language Went Global.

Almost half the world’s people speak one of its daughter languages

In fact, as Spinney notes, nearly one out of every two people on Earth today speaks one of the 400-plus Proto-Indo-European languages. Of course, among the more than 7,000 extant languages, there are four other major language families: Sino-Tibetan, Niger-Congo, Afro-Asiatic, and Austronesian. But Proto dominates. Collectively, 1.7 billion people speak English, Spanish, Hindi, Portuguese, or Bengali as a first language. However, for only 400 million is English their first language. Another 1 billion speak it as a second language, which accounts for the supremacy of English in trade and diplomacy today.

Proto: How One Ancient Language Went Global by Laura Spinney (2025) 334 pages ★★★★☆

How did this happen?

“The speakers of Proto-Indo-European, who might only have numbered a few dozen to begin with, lived between Europe and Asia in the region of the Black Sea,” Spinney notes. “About five thousand years ago, their language exploded out of its Black Sea cradle, spreading east and west and fragmenting as it went.” Because language is never static. The efforts of the French Academy and other purists notwithstanding, languages evolve. In fact, over the course of 500 to 1,000 years, any language will become unintelligible to its original speakers.

Witness, for example, present-day English speakers’ inability to understand Old English (around 650 to 1,170 CE). Middle English (1170 to 1490 CE) is impossible for most of us to understand today. Only in the Modern English of Shakespeare and his contemporaries in the 16th century does English resemble the tongue we speak today. And as anyone who struggles with Shakespeare today, even his language differs from our own in major ways.

To explain why changes like this take place in our languages, I turned to the AI chatbot Claude (Opus 4.1). What follows is word-for-word what Claude reported. It’s worth reading, because in every respect it reflects not just what Laura Spinney writes in Proto but everything else I’ve ever read about linguistics. I’ve merely added subheads to break up the text.

Why languages evolve

Languages are living systems that constantly evolve through the interplay of social, cognitive, and historical forces. Like biological evolution, linguistic change is both inevitable and gradual, shaped by the fundamental ways humans communicate and organize societies.

One primary driver of language change is the inherent variation in how people speak. No two individuals use language identically—differences in pronunciation, word choice, and grammar naturally arise based on factors like age, social class, education, and regional background. When certain variants become associated with prestige or social identity, they may spread throughout a community. Young people often lead these changes, adopting new forms to distinguish themselves from older generations, while some innovations fade and others become permanent features of the language.

The Great Vowel Shift

Sound changes occur systematically through ease of articulation. Speakers unconsciously simplify pronunciation to minimize effort, leading to predictable patterns. For instance, the Great Vowel Shift dramatically transformed English pronunciation between 1400-1700, explaining why English spelling seems inconsistent—the written form fossilized while pronunciation continued evolving. Similarly, consonants may soften or disappear entirely; Latin “octo” became Italian “otto” and French “huit,” showing how the same word transforms differently across languages.

Grammar simplifies over time through a process called regularization. Old English had complex case systems and verb conjugations that Modern English has largely abandoned. Irregular forms tend to become regular—while we still say “went” instead of “goed,” many formerly irregular verbs like “helped” (once “holp”) have regularized. Word order has become more rigid to compensate for lost grammatical markers, making meaning clear without elaborate endings.

Loan words and convergence

Contact between languages accelerates change through borrowing and convergence. English vocabulary is famously hybridized, absorbing words from French after the Norman Conquest, scientific terms from Latin and Greek, and modern technological vocabulary from languages worldwide. Beyond vocabulary, languages can borrow sounds and grammatical structures. Prolonged bilingualism can create entirely new languages—creoles emerge when speakers of different languages need to communicate, developing systematic grammars from initially simplified pidgins.

Technology and social change introduce new concepts requiring new words. The internet age has spawned countless terms—”email,” “selfie,” “googling”—while rendering others obsolete. Meanings also shift through metaphorical extension (computer “mouse”), broadening (“awful” once meant “awe-inspiring”), or narrowing (“meat” originally meant any food).

Education and social networks

Cultural attitudes affect the speed and direction of change. Standardization through education and media can slow change in formal contexts while accelerating the spread of innovations across regions. Social networks determine which changes catch on—innovations spreading from prestigious groups often succeed, while stigmatized features may persist only in isolated communities.

Understanding language change helps explain why Old English reads like a foreign language, why teenagers’ slang bewilders their parents, and why no amount of prescriptive rules can freeze language in place. Languages change because humans are creative, social beings who constantly adapt their communication to new contexts, relationships, and realities. This dynamism isn’t corruption but evidence of language’s fundamental vitality—its capacity to serve human needs across endless cultural transformations.

About the author

Laura Spinney is a British science journalist, novelist, and nonfiction writer. Her account of the 1918 influenza pandemic is the best-known of her six books to date. Born in 1971 in the UK, she holds a BS in Natural Sciences from Durham University. She now lives in Paris, France.

For related reading

I’ve also reviewed the author’s earlier book, Pale Rider: The Spanish Flu of 1918 and How It Changed the World (Was the Spanish Flu of 1918 a greater disaster than World War II?)

For other books on archaeology, see The Lost City of the Monkey God: A True Story, by Douglas Preston and Four Lost Cities: A Secret History of the Urban Age by Annalee Newitz.

Also see Against the Grain: A Deep History of the Earliest States by James C. Scott (This book will challenge everything you know about ancient history) and The Riddle of the Labyrinth: The Quest to Crack an Ancient Code by Margalit Fox (“The Quest to Crack an Ancient Code”).

And you can always find the most popular of my 2,400 reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.