Estimated reading time: 7 minutes

Historians long debated the Great Man Theory of History attributed to the Scottish essayist Thomas Carlyle in 1840. As we have come to understand the contrasting views on either side of the question, some insist that the course of history is set by the ideas and actions of “great men.” Others assert that the currents of their time carry along even these extraordinary leaders, who are merely actors on the stage of history. We hear little of that debate these days, since today we accept that history is shaped both from above and from below. But a close look at World War II might cause us to reexamine that conclusion. Then, four exceptional men—Hitler, Churchill, FDR, and Stalin—played oversized roles in determining the course of history. And that question rises to the surface in Warlords, an intimate examination of the relationships—and the misunderstandings—among the four.

Long-distance relationships filled with conflict

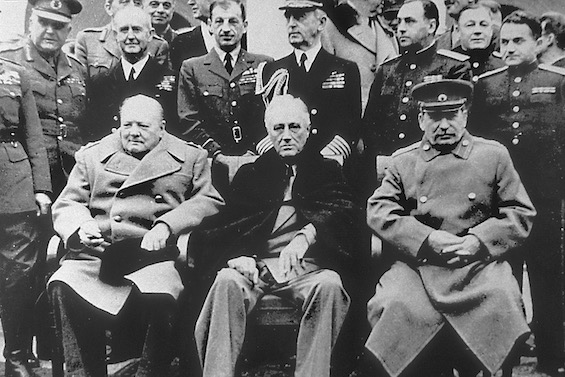

These were largely long-distance relationships. Hitler never met any one of the other three men. FDR encountered Stalin only twice, at conferences in Tehran (December 1943) and Yalta (February 1945) in Churchill’s company. Churchill also met the Soviet leader alone in Moscow in 1942. Only Churchill and FDR developed a face-to-face relationship, meeting eleven times in the course of the war (and once previously in World War I). In Berthon and Potts’ telling, the interaction among the four leaders was even more contentious than most histories suggest. All four possessed giant egos, so conflict was inevitable. The divergent national interests of the countries they led ensured that conflict would be intense. And, understandably, the shifting fortunes of war at times unsettled even the most stable of them.

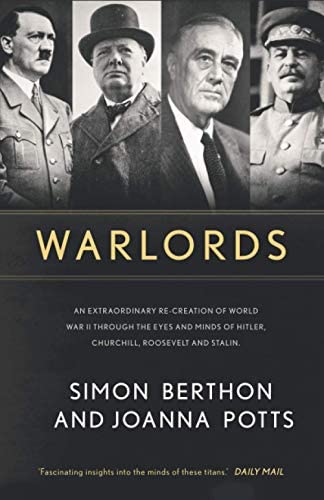

Warlords: An Extraordinary Re-creation of World War II Through the Eyes and Minds of Hitler, Churchill, Roosevelt, and Stalin by Simon Berthon and Joanna Potts (2005) 384 pages ★★★★★

Misjudgments and misunderstandings were rife

The authors make cleat that one or another of the four displayed unusually perceptive views of the others from time to time. But misunderstanding was more common.

FDR and Stalin

For example, FDR consistently misjudged Stalin, naively believing he could take what he said as trustworthy. Far too late, when close to death, Roosevelt came to understand how wrong he had been once Stalin proved he had had no intention of fulfilling the promises he’d made at Yalta.

Stalin and Hitler

Stalin long insisted that Hitler was a rational actor and would never break the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. Only when more than three million Nazi troops swarmed over the Soviet border on June 22, 1941, did he come to face reality. In fact, the invasion so shocked him that he holed up in his dacha for days, refusing to deal with his generals.

Hitler and Stalin on Churchill and Roosevelt

Hitler grossly underestimated both Churchill and Roosevelt, thinking them weak and unable to sustain their commitment to the war. He persisted in this delusional belief until shortly before his own suicide on April 30, 1945. And Stalin thought them both captives of “international capital,” deeply distrusting—to the point of full-blown paranoia—their assurances to support the Soviet war effort. This persisted even after the Western Allies opened up the “second front” in 1944.

FDR and Churchill

The differences between FDR and Churchill were typically less intense. But they started off poorly when the Prime Minister approached the President soon after taking office in May 1940 in hopes of persuading him to steer the United States into the war. FDR had met Churchill once previously, in July 1918, when he was Assistant Secretary of the Navy and visiting Great Britain in the closing months of World War I. “At a dinner I attended he acted like a stinker,” Roosevelt recalled. To make matters worse, Churchill later failed to recall this first meeting. “Is he a drunk?” FDR asked Harry Hopkins when the aide returned from a fact-finding mission to Britain in February 1941, Nearly a year passed before FDR warmed to the Briton.

More fundamental, and longer-lasting, was Churchill’s failure to understand “that nothing Roosevelt said could be taken at face value; nor, despite his surface charm and affability, how impenetrable and elusive the President really was.” Pinning him down was “very much like chasing a vagrant beam of sunshine around a vacant room,” as Secretary of War Henry Stimson wrote in his diary.

Far more consequential was the intense argument that raged from 1942 to 1945 between FDR and Churchill over military strategy. FDR consistently sided with his War Department in pushing for a cross-channel invasion of France. Churchill, fearing another catastrophic failure from an amphibious operation like those at Gallipoli in 1915-16 and Dieppe in 1942, never warmed to the idea. Instead, he insisted on attacking Germany through the “underbelly of the Axis” (a phrase usually misquoted as “the soft underbelly of Europe“).

Churchill’s Balkan strategy

Although the two Allies reached a compromise with the invasion of Sicily in July 1943, Churchill advocated instead—both before and after the Italian campaign—an attack on the Balkans. Initially, he saw that strategy as far preferable to sending tens of thousands of soldiers to die on the beaches of northern France. He also viewed Britain’s control of the Mediterranean as vital to preserving its empire in the Middle East and India—while FDR hoped the war would put an end to the British Empire. “Roosevelt was not fighting Churchill’s war but his own; and the two men had very different long-term objectives,” Berthon writes.

Later, as V-E Day approached, the Prime Minister argued so aggressively with FDR that the President lost patience with him. Relations then came close to the breaking point. Churchill was adamant because he wanted the Allies to drive north from Greece to cut off advancing Soviet troops and prevent Stalin from seizing at least some of Eastern Europe. FDR then still labored under the illusion that Stalin was an honest man (and, in fairness, American military strategists thought Churchill’s proposed plan unworkable). Of course, for what little it may be worth, Churchill’s fear that Stalin would seize nearly all of Eastern Europe proved to be the case.

An admirable example of intensive research

As Simon Bethon notes in a foreword, “This book unashamedly takes the view that, in the war of 1939-45, the personal decisions of the four titans at the heart also dictated its outbreak, its course and its consequences.” In the nearly 400 pages that follow, he makes the case. The eleven-page bibliography and list of published sources that are appended to the text is extensive, clearly reflecting an intense research effort, undertaken primarily by Berthon’s coauthor, Joanna Potts. The book is lucidly written and adds depth to our understanding of the conduct of the most cataclysmic conflict in history.

About the authors

Simon Berthon

Simon Berthon worked for nearly four decades in the British television industry as a producer, director and writer, winning multiple awards in the process. He turned to writing thrillers in recent years, continuing his work in TV as a freelance executive producer and consultant. To date Berthon has written three nonfiction books that tie in with his television productions as well as three thrillers. He divides his time between London, Cambridge and Wiltshire.

Joanna Potts

Joanna Potts is a British historian and researcher who has collaborated with Simon Berthon on several nonfiction books. She is a graduate of the University of Bristol. Like him, she works in the television industry, having undertaken projects for Channel Four and the BBC.

For related reading

See The Duel: The Eighty-Day Struggle Between Churchill and Hitler by John Lukacs—(When Churchill faced Hitler alone) for an assessment of the two men during the early days of World War II.

You might also enjoy:

- 10 top nonfiction books about World War II

- Books about World War II in the Pacific

- The 10 best novels about World War II

- 7 common misconceptions about World War II

- The 10 most consequential events of World War II

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.