Estimated reading time: 9 minutes

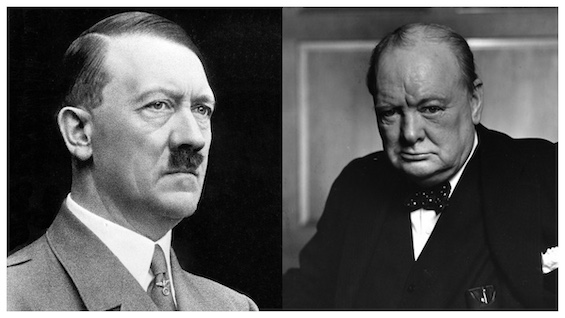

On May 10, 1940, two historic events grabbed the world’s attention. Hitler’s Panzer armies broke through the Belgian and Dutch frontiers. And King George VI asked Winston Churchill to form a new government. To tell the story of the eighty days that followed, historian John Lukacs frames the conflict between Britain and Nazi Germany as a “duel” between Churchill and Adolf Hitler. The book is a worthy account of the early days of World War II in Europe.

In his telling in The Duel, the two leaders faced each other alone during those eighty days. The metaphor is strained, since so many other senior officials were involved in the conflict. And the two men never actually met. But no matter. Contrived metaphor aside, Lukacs tells a story crammed with revealing facts and insights gained from a lifetime of studying World War II in all its dimensions. For any reader with deep interest in the events of that time, this book is well worth reading.

Germany might have won the war in May, 1940

Lukacs writes “during those eighty days in May, June and July 1940 Hitler came closer to winning the war than we have been accustomed to think.” At the same time, he notes, Churchill was in a far less secure position than most accounts of the time would imply. This is Lukacs’s style. He’s invariably termed a “maverick historian,” and it’s clear from his writing that he relishes challenging established views.

But here the facts as I know them support his conclusion. Because throughout much of May, 1940, Winston Churchill’s leadership of the War Cabinet was uncertain. Both Neville Chamberlain and Lord Halifax commanded far greater support in the Commons. And “the miracle of Dunkirk,” when the British successfully evacuated 338,000 troops from France, was a very close thing. A shift in the weather on May 26 and 27 could have doomed the attempt. And had the evacuation gone awry, Churchill might well have found it difficult to continue to prosecute the war.

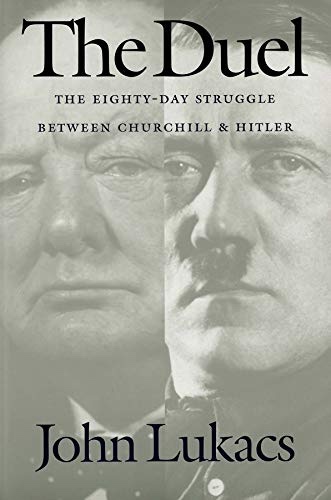

The Duel: The Eighty-Day Struggle Between Churchill and Hitler by John Lukacs (1990) 258 pages ★★★★☆

A towering task

Churchill was fond of remarking that he had taken on a great burden when he stepped into the role of Prime Minister on May 10, 1940. A huge burden it was. The monumental task facing him during the eighty days that followed was four-fold:

- Bolster British public opinion, which verged on defeatism as the country faced the prospect of a Nazi invasion

- Insulate himself from his many internal enemies, not just in the House of Commons but in his own War Cabinet. There, two much more popular men, Neville Chamberlain and Lord Halifax, had both worked tirelessly to appease Hitler—and Halifax was pressing him to negotiate peace with Hitler.

- Persuade the French to continue to fight (which they did only halfway through the eighty days)

- Attempt to convince Franklin D. Roosevelt that the United States must urgently come to his aid, if Great Britain were to prevail against the Nazi juggernaut

As Lukacs details, Churchill succeeded in three of the four aspects of this task, losing only when the French sought an armistice with Germany.

Assessing the military skills of Hitler and Churchill

The Duel is far more than a chronology of the two men’s lives and work during those eighty days. Lukacs sets the scene with his assessment of the military picture as it unfolded. And he probes deeply into their personalities, offering a contrast that seems a little forced at times. His assessment of Hitler’s abilities is far more generous than I’ve read anywhere else. HItler was “not a madman,” he writes. He was “the greatest revolutionary of the twentieth century.” And, departing from the conventional wisdom, he regards Hitler as both a skillful diplomat and an able military planner. Others reject both judgments.

My own reading about the two men and the conduct of the war makes clear to me that Hitler’s strategic thinking was poor—he was right far less often than wrong. Yes, the blitzkrieg into the Low Countries and France was a brilliant plan. But he blundered again and again on a strategic level on the Eastern Front, beginning with Operation Barbarossa. For example, the invasion of the Soviet Union might have succeeded quickly if Hitler had concentrated his forces on a drive directly eastward toward Moscow. Instead, the Nazis advanced into the USSR on an 1,800-mile front. Then, later, when a dramatic push might have enabled him to capture Moscow, Hitler ordered his most capable army southward to take Stalingrad. And we know how that turned out.

Errors in the West as well as on the Eastern Front

HItler compounded these errors by holding his most effective forces back from Normandy long after his generals in the field had realized the Allies’ main thrust had already arrived there. And he retained operational control at the divisional level, repeatedly frustrating his generals.

Of course, Churchill was far from gifted as a military strategist, either. He’d already shown that in World War I, when he conceived the tragically misguided plan to invade Gallipoli in Turkey And he fought bitterly against American plans for the invasion of Normandy and southern France in 1944. In both wars, Churchill was fixated on directing the major thrust of the attack against Germany through the Balkans for political reasons. (Protecting British outposts in the Middle East in World War I, and preventing Stalin from seizing southeastern Europe a quarter-century later.)

Desperate measures to hold off a French surrender

In June 1940, as French resistance was crumbling, Churchill frantically sought to persuade the French to stay in the war. On four occasions in May and June he flew to France to meet with Prime Minister Paul Renaud and Maxime Weygand, commander of the French army. Increasingly desperate to sway them as Nazi troops drove further into the French heartland, he offered a series of proposals that, in hindsight, appear naive. First, he urged the French to dispatch their fleet to British ports even as they entered into talks with Hitler to surrender. Lukacs notes, “It was not an argument that would impress Pétain and his supporters.”

Then, amazingly, he endorsed a plan to draw the French into a merger of their two countries! Churchill’s War Cabinet agreed to the plan, however, absurd though it seems today. “The two governments declare that France and Great Britain shall no longer be two nations, but one Franco-British Union,” the proposal read. “Every citizen of France will enjoy immediate citizenship of Great Britain, every British subject will become a citizen of France.” And, even harder to understand, the arch-nationalist General de Gaulle was enthusiastic about the idea. Of course, Marshal Pétain and General Weygand thought even less of this harebrained scheme. As one of their supporters noted, “Better be a Nazi province. At least we know what that means.” It’s astonishing to think just how desperate were the British midway through those eighty days.

Strange coincidences

Two “coincidences” bookend Lukacs’s story. On May 10, as noted above, Churchill took office as Prime Minister on the very day that German armies broke through the French frontier. And on July 31, two equally momentous events took place. Roosevelt made the firm decision to sell Churchill the aging destroyers he’d been begging for. Churchill read it as a signal that the United States would eventually enter the war in force.

On the same day, Hitler announced to his most senior generals that he was likely to invade the Soviet Union before proceeding with Operation Sea Lion, the landing in England. In fact, his naval chief, Admiral Raeder, had told him “the German navy could not responsibly guarantee a wide coastal landing in England before next year.” And Hitler may also have been unconvinced by Hermann Göring’s claim that he could gain complete aerial supremacy over the British. (Göring was a morphine addict and had grown increasingly grandiose and unreliable as the prospects of victory dimmed.) And air supremacy was a prerequisite for the invasion. In the event, of course, the Luftwaffe lost the Battle of Britain. And Hitler never green-lighted the invasion.

About the author

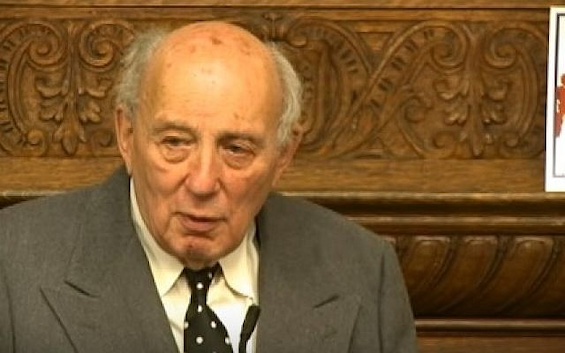

John Lukacs died on May 6, 2019 at the age of 95. His New York Times obituary identified him as a “maverick historian, prolific author and self-professed reactionary.” A Hungarian-American, born in Budapest of Jewish converts to Roman Catholicism, he studied history at the University of Budapest. In 1944, he escaped the labor battalion for Jews that the Nazis had forced him to join. Lukacs emigrated to the United States in 1946 after receiving his doctorate. He became a professor of history at Chestnut Hill College in Philadelphia and a visiting professor at Columbia, Princeton, and other universities.

Lukacs was the author of 35 books and innumerable articles, essays, and other works. In 2006, he wrote, “Nationalism, not Communism, was the main political force in the 20th century, and so it is now,” And that’s a theme he reiterates in The Duel. Lukacs was married three times and had two children by his first wife.

For related reading

For other books that offer insight on Hitler and Churchill, see:

- Darkest Hour: How Churchill Brought England Back from the Brink by Anthony McCarten (New insight into Prime Minister Winston Churchill)

- Warlords: An Extraordinary Re-creation of World War II Through the Eyes and Minds of Hitler, Churchill, Roosevelt, and Stalin by Simon Berthon and Joanna Potts (Misjudgments and misunderstandings in World War II)

- The Splendid and the Vile: A Saga of Churchill, Family, and Defiance During the Blitz by Erik Larson (An intimate view of Winston Churchill in WWII)

You’ll find more information about the war here:

- 10 top nonfiction books about World War II

- 7 common misconceptions about World War II

- The 10 most consequential events of World War II

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.