Estimated reading time: 7 minutes

A Nazi atomic bomb? The fear that Werner Heisenberg, Otto Hahn, and other Nobel-winning German physicists would develop nuclear weapons for Adolf Hitler began to seize hold in the upper reaches of the American government when Albert Einstein’s letter to President Franklin Roosevelt arrived in the White House in August 1939.

But it wasn’t long before speculation about German nuclear research reached a much wider public. “No one had heard of uranium fission before January 1939; by December, more than a hundred papers on the topic had appeared worldwide.” And the fear of a Nazi atomic bomb was well founded. “Two years before the start of the Manhattan Project” . . . Germany’s “Uranium Club had scientists working on two key aspects of nuclear weapons: enriching uranium and producing a self-sustaining chain reaction. The German atomic bomb project was off to a rip-roaring start.”

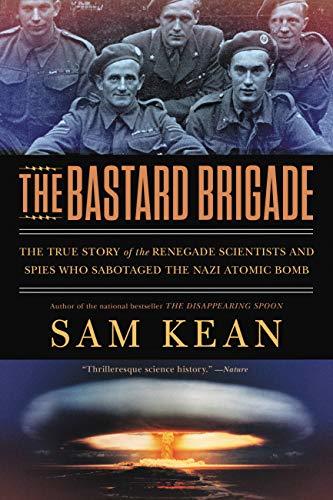

The Bastard Brigade: The True Story of the Renegade Scientists and Spies Who Sabotaged the Nazi Atomic Bomb by Sam Kean (2019) 465 pages ★★★★☆

Given the universal perception that German physicists were the best in the world, the Allies feared a nuclear attack almost throughout the war—as late as the middle of 1944. And that was even without assuming the Nazis had succeeded in building an atomic bomb, because only a small quantity of radioactive material is needed. “Fear of dirty bombs continued to fester in the minds of American official in the run-up to June 6,” and planes were sent with Geiger counters to sweep the northern coast of France in advance of the Normandy invasion.

Unaccountably, then, the Allies had launched the Alsos Mission to investigate how far the Nazis had progressed in the field only in September 1943. “People called it the Bastard Unit” because it worked independently, hence the title of Sam Kean’s often jaw-dropping account of the perilous effort to explore and undermine the German nuclear program.

Other efforts to undermine the German atomic bomb project

The Alsos Mission was not the Allies’ first or only effort to hobble the Nazi atomic bomb project, and for good reason. In fact, fully aware that the Germans used large quantities of heavy water in their research, there were multiple efforts almost throughout the war (1940-44) to blow up the world’s only large-scale deuterium-production plant at Vemork in Norway, to steal huge shipments of the stuff, and (in 1944) to destroy a ship thought to be carrying tons of it on its way to Germany. But it wasn’t until September 1943 that the British and Americans launched the Alsos mission.

The broad scope of the mission

Great Britain and the United States organized the Alsos Mission in the wake of the September 1943 Allied invasion of Italy to assess the Nazis’ progress toward creating nuclear, chemical, and biological weapons and the technology to deliver them—and to prevent their capture by the Soviet Union. In addition to the nuclear program, the mission focused on the German “Vengeance-weapons“—the V-1 cruise missile, V-2 ballistic missile, and V-3 cannon—all of which American military leaders feared might carry atomic warheads. The more than one hundred soldiers, spies, and scientists who eventually joined the mission followed closely behind the front lines in Italy, France, and Germany as the Allies closed in on the German heartland. From time to time they crossed into enemy-held territory to grab valuable resources before the Germans could destroy them or snatch Nazi scientists before they could escape or fall into Soviet hands.

Characters out of the history books

The amazing tale Sam Kean tells in The Bastard Brigade revolves around a handful of extraordinary characters:

- Moe Berg, the eccentric former Major League Baseball catcher who spoke at least half a dozen languages and worked as a spy for the OSS: “he could read hieroglyphics and recite Edgar Allan Poe’s entire poetic oeuvre . . . [and] bought dictionaries ‘to see if they were complete.'”

- Dutch-born American physicist Samuel Goudsmit, the chief scientist for the Alsos Mission whose parents died at Auschwitz

- Nobel-Prize-winning physicist Werner Heisenberg, author of the Uncertainty Principle and head of the Nazi atomic bomb program. Kean describes him as “essentially a boy scout with a hypertrophied brain.”

- The Nobel Laureate husband-and-wife team of Frédéric Joliot-Curie and Irène Joliot-Curie, both active in the French Resistance

- Joe Kennedy, Jr., JFK’s older brother who perished in a spectacular plane crash as a Navy pilot in World War II. Kennedy was engaged in a vainglorious effort to best his brother’s medal-winning feats on PT-109. He died on what in hindsight was clearly a futile mission to destroy what Dwight Eisenhower feared was a German launch site in northern France for nuclear weapons.

- US Army Colonel Boris Pash, a veteran of the White Army in the Russian Civil War who taught physical education and science at Hollywood High and later headed the Alsos Mission for the Allies

Every one of these exceptional people has been the subject of multiple references in history books and, in some cases, many biographies as well. The same goes for many of the fourteen people Kean cites at the back of the book in a list of minor characters. The Bastard Brigade is, above all, an account about people whose stories deserve to be told.

How this book is organized

Kean has done an admirable job organizing the unruly material that underpins his story. The Bastard Brigade is divided into six sections, each roughly corresponding to one year of the war (“Prewar, to 1939,” “1940-41,” “1942,” and so forth). In each section, he traces the trajectory of the principal characters as they moved ever closer to intersecting in the Alsos mission. But in doing so, Kean frequently digresses, layering in colorful tales that help to flesh out the leading actors in the high-stakes game of nuclear competition. Many of those digressions might have hit the cutting-room floor in a book written by an academic historian. But for Kean—and the reader—they add color and depth that would otherwise be missing from a recitation of facts in chronological order.

Kean’s use of these often little-known episodes and insights is sometimes delightful. Here are just a few examples:

- Moe Berg’s tendency to wander off on his own when he became bored with his missions for the OSS.

- The facts that Joe Kennedy “was a terrible pilot” and the plane that killed him was a flying bomb jam-packed with explosives

- The German plans for the V-3 Hochdruckpumpe (high-pressure pump) or “Busy Lizzie,” a 416-foot cannon that shot nine-foot bullets.

The author’s style is . . . well, informal

Sam Kean writes in a style that’s best described as loose. Casual, if you will. Conversational. Vernacular. Even occasionally drifting over the line into sexual innuendo or scatological allusions. This approach makes for an easier and faster read, but it can be jarring. And at times it detracts from the impact of the surprises he dug out of the historical record. The upshot is that Kean’s style cheapens this otherwise revealing and enjoyable book.

For related reading

This book is a runner-up to the 10 top WWII books about espionage.

I’ve also reviewed Caesar’s Last Breath: Decoding the Secrets of the Air Around Us by Sam Kean (An eye-opening book about air).

You might also be interested in:

- 5 top nonfiction books about World War II

- The 10 best novels about World War II

- 7 common misconceptions about World War II

- The 10 most consequential events of World War II

- Top 20 popular books for understanding American history

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.