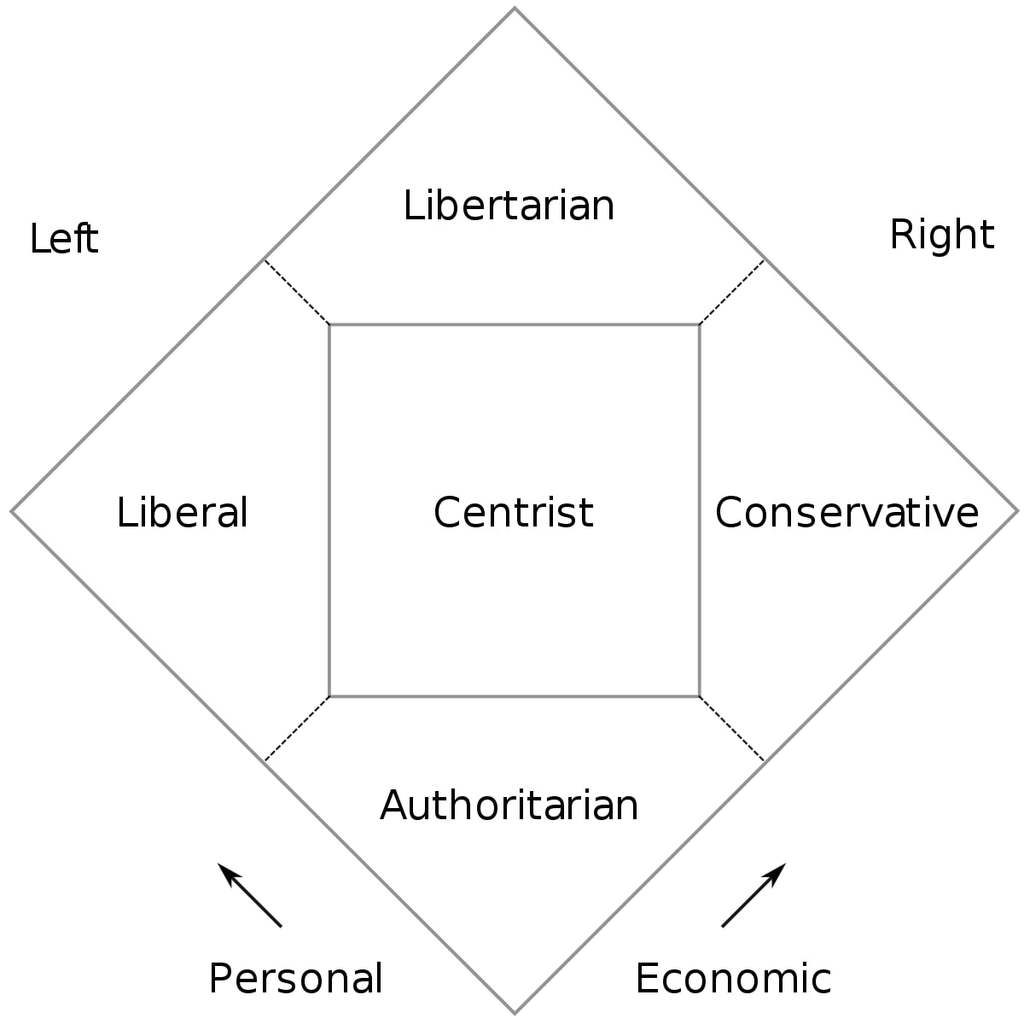

Violations of the laws of physics notwithstanding, there is a truly excellent reason to read this intriguing new exercise in space opera. It’s one of the best explorations I’ve ever come across in the genre about politics and political philosophy. (Kim Stanley Robinson’s Red Mars trilogy offers much the same.) Oh, the book is about biowarfare, too, and some new-agey philosophy about how consciousness underpins all reality. But it’s the politics that shine. And in The Eleventh Gate award-winning science fiction author Nancy Kress excels in dramatizing the consequences of putting fully into practice two of the leading political philosophies of the early twenty-first century: libertarianism and the welfare state.

The Eleventh Gate by Nancy Kress (2020) 387 pages @@@@ (4 out of 5)

Civilization on Earth has died in this space opera

The Eleventh Gate is set a few hundred years in the future. Earth has long since become unlivable for all but a handful of primitive survivors. “Earth’s death agonies had been swift by extinction standards, but not instantaneous. It had taken four or five generations for desertification, biowarfare, rising oceans, and, finally, all-out war to kill Terran civilization.” But one hundred fifty years ago a small number of pioneers set out for the stars, taking advantage of the wormholes discovered near Earth-like planets across the galaxy. And now new human civilizations have sprung up on the Eight Worlds linked by those gates through the heavens. (Earth is counted as one of the eight.)

Two political philosophies contend for dominance

On three of the newly settled planets, the immensely wealthy Peregoy family rules over a corporate welfare state. Another three planets are governed by the superrich Landry family, which follows libertarian principles with religious zeal. The seventh planet more closely resembles old Earth, with twenty-six ethnically and linguistically diverse nations loosely collaborating in a planetwide Council of Nations akin to today’s UN.

The dichotomy between libertarianism and the authoritarian welfare state could not be more stark. On the Landry planets, inequality has run its course, demonstrating that unfettered capitalism will inevitably impoverish all but a handful of the very rich. (Don’t believe that? Read Piketty.) And where the Peregoys rule, and all basic needs are met by the state, millions have fallen prey to welfare dependency. The contrast is overdrawn, but the point is made.

On both the Landry planets and those run by the Peregoys, dissent has been on the rise for some time. The Landrys adamantly refuse to help those who are out of work in a society where precious few new jobs are created. And people living under the Peregoys have come to take for granted all the benefits the state confers on them—and they resent the loss of any ability to make the critical decisions that affect their lives. Both systems are on shaky ground as a result. Now, what happens when the Peregoys and the Landrys go to war? There is no better way to impose stress on a political system than to demand that people who already feel victimized by their government must sacrifice to support a war. And that’s the tale Nancy Kress tells so colorfully in this inventive if flawed space opera.

Now, about that spacey New Age philosophy

Since the days of live Greek theater, storytellers who write themselves into a box have solved seemingly unsolvable problems with a device called deus ex machina. Out of the blue, they introduce a god or supernatural being who can—miraculously!—fix everything. Now, in The Eleventh Gate, the deus ex machina doesn’t come out of the blue. We’ve been forewarned, in a sense, with frequent references to ruminations by philosophers and physicists such as Arthur Eddington, who speculated that “the stuff of the world is mind-stuff” and “the substratum of everything is of mental character.” But what Kress does with this line of thinking is . . . you got it . . . to create a god. I shun fantasy to avoid this sort of thing, and I could have done without it here.

And about those laws of physics

There’s a problem with space opera. A big one. The genre works only because science fiction authors imagine spaceships slipping rapidly through such theoretical devices as wormholes or “gates,” traveling from one distant planet to another. And those planets are often located tens or hundreds of light-years apart. Fair enough, I suppose. The genre asks us to suspend disbelief. But I find it strains credulity in the extreme for me to believe that a wormhole, or any other literary device, could so cavalierly challenge the laws of physics.

Assume, if you will, that such wormholes exist and work in the fashion that sci-fi writers presume. Now ask yourself, how much time would elapse if people traveled a distance of one hundred light-years? Well, for them, virtually none, presumably. Writers tend to assume that travel through a wormhole is instantaneous. But for the people they leave behind? Surely, a hundred years. Or, at least that’s how I’m forced to understand Albert Einstein’s concept of time dilation. Admittedly, I don’t know that’s what would happen—but nobody knows. And how often do we space opera fans read about that?

If the Empress back in the Brobdignagian Empire was fifty years old when a spaceship departed, chances are slim she’d still be on the throne two hundred years later when that spaceship returned. So, if you’re looking for a realistic depiction of time dilation, skip most of the genre and check out instead Joe Haldeman’s brilliant classic, The Forever War. There’s a very good reason to read Nancy Kress’ latest venture into space opera, as I’ve explained, but not that.

About the author

Nancy Kress has been writing science fiction and fantasy since 1976. Her breakthrough came in 1991, when she won the Hugo and Nebula Awards for her novella, Beggars in Spain. Kress’ published work includes more than thirty novels and ten collections of short stories. She has won the Nebula six times, the Hugo Award twice, and the John W. Campbell Memorial Award and the Theodore Sturgeon Memorial Award. Kress lives in Seattle with her husband, a fellow author.

To get a sense of just how good Kress’ work can be, check out my review of her novel, Tomorrow’s Kin: Hard science fiction doesn’t get much better than this. Tomorrow’s Kin is hard sci-fi, and it’s about evolutionary biology, one of the fields in which Kress appears to be especially knowledgeable. But it’s also a grim story that is never predictable. Kress does a terrific job building suspense to the breaking point. This novel is an ideal point of entry for the two books that follow in the Yesterday’s Kin Trilogy.

For further reading

For more good reading, check out:

- The ultimate guide to the all-time best science fiction novels;

- Great sci-fi novels reviewed: my top 10 (plus 100 runners-up);

- Seven new science fiction authors worth reading; and

- The top 10 dystopian novels reviewed here (plus dozens of others).

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, plus a guide to this whole site, on the Home Page.