The tagline on the cover of Darwin’s Children reads “Evolution has changed the face of the world.” In the sequel to his brilliant 1999 novel, Darwin’s Radio, Greg Bear now spells out the ways in which a dramatic event in the evolution of the human race has laid the foundation for a posthuman future. Not through human agency such as implanted chips or genetic editing, but naturally, by means of an evolutionary process that responds to the growing stress in the human environment.

While it may be possible to read Darwin’s Children as a standalone effort, I don’t recommend it. If Bear’s thinking on this subject intrigues you, start with his Nebula-Award-winning novel, Darwin’s Radio. Be careful. If you do opt to read that book first, this review will spoil the story for you. If you haven’t already read my assessment of Darwin’s Radio, begin there.

Darwin’s Children (Darwin #2 of 2) by Greg Bear (2002) 512 pages ★★★★☆

Four characters confronting the posthuman future

In Darwin’s Children, the cast of characters shifts. CDC Director Mark Augustine has been sidelined by bureaucratic infighting and plays only a minor role. Of the four original principals, three continue to bring focus to the story: Kaye Lang Rafelson, Mitch Rafelson, and Christopher Dicken. And now Kaye and Mitch’s eleven-year-old daughter, Stella Nova Rafelson, enters center stage. She is one of the first wave of SHEVA children demonized and incarcerated by a terrified and vengeful government. And it is really she who is the protagonist of this sequel to the story in which she was born.

“I am not human”

Darwin’s Children opens at “SHEVA + 12,” or a dozen years since the emergence of the SHEVA virus in America. Stella is eleven and on the run with her parents. The draconian forces of the Right-Wing government, riding a wave of fear and hatred fanned by hysterical media reports, is rounding up all the SHEVA children. (“The last thing Mark Augustine had ever imagined he would be doing was running a network of concentration camps.”) And in the midst of the chaos, “For the first time, Stella had formally proclaimed: ‘I am not human.'”

As the story proceeds, we encounter increasing detail about the many changes that make this claim credible. And despite everything—despite the widespread abortions of SHEVA fetuses, the massacres of SHEVA children by terrified people, and all the efforts of governments everywhere to suppress the growth of the new species—Stella is far from alone. “Worldwide, in two waves separated by four years, three million new children had been born.” Thus we gain our first glimpse of the posthuman future. Genus homo has taken another step forward.

The book’s Part Two is set at “SHEVA + 15,” and Part Three at “SHEVA + 18.” Thus, we follow Stella’s life until she reaches the age of seventeen. Then, she has found her way into a community of young people like herself. Meanwhile, we observe Kaye and Mitch’s frantic efforts to relate to their ever-stranger daughter as the posthuman future begins to emerge.

“An infinitely devious shell”

As the end of the story approaches, Kaye reflects, “Nearly all her life, [she] had believed that understanding biology, the way life worked, would lead to understanding herself, to enlightenment. Knowing how life worked would explain it all: origins, ends, and everything in between. But the deeper she dug and the more she understood, the less satisfying it seemed, all clever mechanism; wonders, no doubt, enough to mesmerize her for a thousand lifetimes, but really nothing more than an infinitely devious shell.” And she concludes, “Nature is a bitch goddess.”

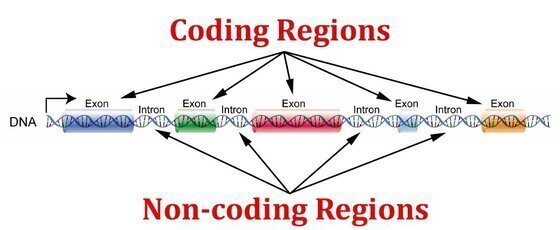

About the science in this novel

In a section labeled “Caveats” at the conclusion of Darwin’s Children, Bear writes, “Much of the science in this novel is still controversial. . . However, all of the speculations found here are supported, to one degree or another, by research published in texts and in respected scientific journals. I have gone to great pains to solicit scientific criticism and make corrections where experts feel I strayed over the line.” And he adds, “The theological speculations presented here are also based on empirical evidence, personal and culled from a number of key books.”

For more reading

Be sure to check out Darwin’s Radio (Darwin #1 of 2) by Greg Bear (A brilliant novel about accelerated evolution) and his Blood Music (A biological technothriller about genetic engineering).

In “A Brief Reading List” following the text of this novel, Greg Bear recommends “a concise, elegantly written and conservative view of neo-Darwinian evolutionary theory . . . Richard Dawkins’s River Out of Eden: A Darwinian View of Life.”

For more good reading, check out:

- The ultimate guide to the all-time best science fiction novels

- Great sci-fi novels reviewed: my top 10 (plus 100 runners-up)

- Seven new science fiction authors worth reading

- The top 10 dystopian novels reviewed here (plus dozens of others)

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, plus a guide to this whole site, on the Home Page.