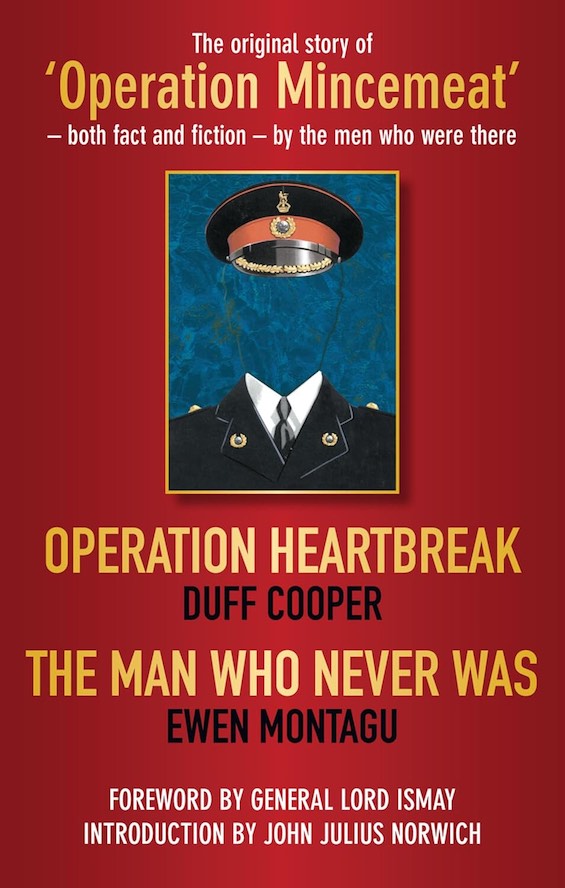

When we think of Allied operations in World War II designed to fool the Nazis, most of us think “Normandy.” After all, the elaborate efforts to conceal the time and place of D-Day famously included a fake army and hundreds of inflatable tanks, airplanes, and artillery pieces. Not to mention all the Abwehr spies the British had turned in the Double Cross System. But two years earlier the British mounted a brilliant deception to shield the invasion of Sicily. In Operation Mincemeat, British military intelligence persuaded the Germans that Allied forces would invade Greece and Sardinia instead. The story first broke in 1950 when Duff Cooper, the man in charge of the effort, told a version in a novel called Operation Heartbreak. Three years later, a naval officer, Ewen Montagu, revealed in detail in The Man Who Never Was how he and his colleagues had pulled off the operation.

Three books tell different versions of the story

More than 70 years have passed since the publication of Montagu’s book. Long-classified British intelligence files, memoirs, and journals have appeared with additional detail. And much of it contradicts what Cooper and Montagu wrote. It’s all laid out in WWII historian Ben MacIntyre’s jaw-dropping 2010 book, Operation Mincemeat: How a Dead Man and a Bizarre Plan Fooled the Nazis and Assured Allied Victory.

What follows here is a master class in historiography. We’ll compare two books written seven decades ago about a single extraordinary event with what historians have since learned about that event. In this way, we’ll gain insight into how history is written—and how it can evolve over the years.

Operation Heartbreak by Duff Cooper, 1st Viscount Norwich (1950) 176 pages and The Man Who Never Was: The Original Story of “Operation Mincemeat”—Both Fact and Fiction—by the Men Who Were There by Ewen Montagu (1953) 192 pages ★★★★☆

How “facts” can evolve

Operation Heartbreak

Duff Cooper’s Operation Heartbreak is fiction, pure and simple. It ignores or glosses over the extraordinary complications and frustrations that plagued Ewen Montagu and his colleagues. The novel is the story of a frustrated British career soldier named Willie Maryngton whose only ambition in life is to fight the Germans in battle. He had enrolled at Sandhurst, the British military academy, only in August 1917 and left far too late to fight in France before the Armistice.

Worse is to come for Willie. By the time war breaks out again in 1939, he is too old for active service. Now a captain in the reserves, he struggles in vain to obtain a waiver and enter the fighting. Then he dies of pneumonia. And his ambition is fulfilled only as a corpse when military intelligence fits him up with fake correspondence to misdirect the Germans about the invasion of Sicily. Cooper devotes little space and only spare details about Operation Mincemeat, which he calls Operation Heartbreak. But he breaks the government’s silence about the deception. This paves the way for Montagu to write his own “factual” account.

The Man Who Never Was

Ewen Montagu’s account of Operation Mincemeat is mostly true. He writes about a colleague named “George” in a brainstorming session who suggests dropping a corpse behind the lines in France with a radio transmitter. “This was not one of his better inspirations,” Montagu notes, ” and we rapidly demolished it.” But that off-the-wall idea later comes back to life in a new iteration. The result is, of course, to drop a corpse dressed like a British army major with a briefcase attached containing top-secret letters. The most important one is from the Deputy Chief of the Imperial General Staff to a senior commander in the Mediterranean. And that letter indicates that the Allies will attack Greece and Sardinia instead of the more obvious target of Sicily, with only a diversionary attack there.

Montagu describes in exhaustive detail all the work to find a suitable corpse, obtain permission to use it, write the many letters the corpse would be carrying (including a photo and love letter from the man’s fiancée, “Pam”), and then persuade—with great difficulty—the military and political leadership to approve the operation. But once he has the green light, Montagu gives elaborate instructions to the captain of the submarine who will release the body off the coast of Spain. He’s selected a spot where a German spy is active. And he knows the Spaniards will turn the briefcase over to him.

Montagu’s post-war research

Because the invasion of Sicily goes off without a hitch, it’s abundantly clear that the deception has worked. The Nazis had redirected forces from the island to Sardinia in the north and Greece in the east. But he learns after the war, just how effective the operation had truly been. German intelligence files make it clear that the Nazi military leadership—and Adolf Hitler himself—had bought the story. In fact, it was two days after the July 10, 1943 invasion that they finally began to realize the truth.

Operation Mincemeat

In his book, MacIntyre contradicts the convenient untruths and obfuscations of Montagu’s own account. For example:

- It was not Montagu alone who managed the case but Montagu working with a Royal Air Force officer named Charles Cholmondeley (pronounced “Chumley”; don’t you just love the English?). And the original idea for the plot had been cooked up several years earlier by a certain naval commander, Ian Fleming, the creator of James Bond, then a Naval Intelligence officer. Montagu conflates the two and refers to them both as “George.”

- The dead body washed onto the Spanish shore to launch the plot was far from the wholly fictional British army captain Willie Maryngton whom Cooper imagines. It was that of Glyndwr Michael, a Welsh homeless man who died from ingesting rat poison containing phosphorus. It was not, as Montagu had asserted, a middle-class Scotsman who died an honorable death in a hospital. And he never asked the Welshman’s family for permission to use his body.

- The famous English pathologist who assured Montagu and Cholmondeley that no one would discover the true cause of death of the man now rechristened “Major William Martin” was clearly mistaken. Glyndwr Michael had died from phosphorus poisoning, which leaves distinctive traces in the body that a competent pathologist could detect. However, the eminent British pathologist had told Montagu that there were no pathologists in Spain who could match his expertise.

Montagu misunderstood the Germans’ reactions

Montagu writes that the Nazis “swallowed Mincemeat whole.” In truth, they didn’t. Because MacIntyre turned up a host of surprising facts about the Germans’ reaction to the deception.

- For instance, the Abwehr agent in Spain who examined the phony papers on “Major Martin’s” body and declared them genuine might well have had his doubts. But no matter. He was desperate to prove he could deliver high-value intelligence to Berlin. So he was strongly inclined to pass along the documents in “Major Martin’s” briefcase no matter what he thought of their authenticity. He himself was one-quarter Jewish and feared being sent back home.

- A “German spy” sent to England to investigate the bona fides of “Major Martin” was a figment of the Nazis’ imagination. British intelligence had captured, turned, or executed every single Abwehr agent infiltrated into Britain—a fact that was still a secret when Montagu wrote his book in the early 1950s.

- The Abwehr officer in Berlin who was the ultimate authority on the authenticity of the documents and was Hitler’s favorite intelligence analyst was easily able to detect the phoniness of “Martin’s” papers. But he chose to reassure Hitler because he was a dedicated anti-Nazi. He was prepared to do anything to help the Allies win the war. In fact, many in the Abwehr were anti-Nazi. The boss, Admiral Wilhelm Canaris, was later executed in the wake of the failed von Stauffenberg assassination plot.)

In other words, the Germans knew perfectly well that “the man who never was” was a hoax. But those who knew refused to pass the truth up the chain of command.

About the authors

Duff Cooper, Ist Viscount Norwich (1890-1954) was a Conservative British politician and diplomat who served in the Cabinet in the years both before and during World War II. He famously resigned as First Lord of the Admiralty in 1938 in protest against Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain’s capitulation to Adolf Hitler at Munich. Chamberlain’s successor, Winston Churchill, brought him back to the Cabinet in a series of senior posts. But he was a member of Churchill’s inner circle and understood to be a close advisor of the Prime Minister. He wrote a memoir as well as Operation Heartbreak, his only novel.

Ewen Montagu (1901-85) was a British judge, Naval intelligence officer, and author of three books, including The Man Who Never Was. Born into an aristocratic Jewish family, he served in the First World War before studying at Trinity College, Cambridge and Harvard University. He worked as a barrister for many years, enlisting in the Naval Reserve in 1938. Montagu served in the Naval Intelligence Division of the British Admiralty, rising to the rank of Lieutenant Commander. He was the Naval Representative on the XX Committee, which oversaw the running of double agents. Operation Mincemeat was one of the committee’s most celebrated successes. And it was Montagu who codeveloped the idea with another officer for the operation. One of the junior officers who also played a role in the deception was Ian Fleming, later the author of the James Bond novels.

For related reading

For more information about what I’ve written above, see:

- Operation Mincemeat: How a Dead Man and a Bizarre Plan Fooled the Nazis and Assured Allied Victory by Ben MacIntyre (How the Allies fooled the Nazis with a corpse)

- Double Cross: The True Story of the D-Day Spies by Ben MacIntyre (Operation Double Cross: a new spin on why the Normandy invasion succeeded)

- The Ghost Army of World War II: How One Top-Secret Unit Deceived the Enemy with Inflatable Tanks, Sound Effects, and Other Audacious Fakery by Rick Beyer and Elizabeth Sayles (An entertaining account of deception in World War II)

- At Long Last, a Gold Medal for America’s World War II ‘Ghost Army’” (New York Times, March 21, 2024)

Check out 10 top WWII books about espionage.

You’ll find other great reading at:

- 10 top nonfiction books about World War II

- The 15 best espionage novels

- Good nonfiction books about espionage

- The best spy novelists writing today

And you can always find the most popular of my 2,400 reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.