The events of the years 1937 through 1941 appear fixed in time. It seems foreordained that Britain, France, the US, and the USSR would have gone to war with Nazi Germany under any circumstances. But that was assuredly not the case, as historian Benjamin Carter Hett makes abundantly clear in his illuminating portrayal of the period, The Nazi Menace. In fact, confusion reigned throughout those years, with the major players stumbling through thickets of uncertainty about one another’s intentions. The forces lined up only haphazardly into the now-familiar split between Allies and Axis. And the alliances in the war that ensued shocked and surprised many of those whose actions had made it inevitable.

The Nazi Menace: Hitler, Churchill, Roosevelt, Stalin, and the Road to War by Benjamin Carter Hett (2020) 402 pages ★★★★★

No one really knew who would be fighting whom

“By early 1939,” Hett writes, “there was little doubt that war was coming in Europe, and coming soon. What was not clear was who would be fighting whom.” Hett explains: “The war of 1939 might have been Germany and Poland against the Soviets, with the Western democracies neutral.” Hitler certainly tried long and hard enough to persuade the Poles to join him in an alliance against Stalin. As he was fully aware, most Poles feared the USSR more than Nazi Germany. And his attention was always drawn eastward toward the Soviet Union.

Alternatively, among other possibilities, the war might have faced off “Germany against the democracies, with Poland and the Soviet Union neutral.” But that was not a given. Adolf Hitler’s order to attack the Low Countries and France was an impulsive, last-minute decision that horrified his general staff.

The largest cast of characters ever

The Nazi Menace opens with the largest list of characters I’ve ever seen in any book, with the possible exception of War and Peace. In fact, I’m not sure Tolstoy’s masterpiece would even come close. Hett’s list weighs in at thirteen pages. Included are the great, the near-great, and the inconsequential from Germany, Britain, France, Italy, the United States, and the Soviet Union. All the usual suspects are there: Hitler, Chamberlain, Churchill, Roosevelt, Stalin, and their closest advisers. Lots of generals and cabinet ministers adorn the list. But Hett enlivens his tale by devoting special attention to a passel of individuals little known to the public. Here are just a few of them:

- Col. Friedrich Hossbach (1894-1980), Hitler’s armed forces adjutant (liaison) from 1934 to 1938. Hossbach, who was brutally candid, was a rare individual who told the Führer the truth whether he was likely to welcome it or not. He was the author of the Hossbach Memorandum, which memorialized Hitler’s sensational address to the Nazi military and foreign policy leadership (November 5, 1937). At that event, the Chancellor declared his intention to wage war in Eastern Europe but not attack Britain and France. Hett views the meeting as a turning point in the generals’ views of Adolf Hitler, igniting wider resistance.

- R. J. Mitchell (1895-1937), who designed the Spitfire and twenty-three other high-performance aircraft. The Supermarine Spitfire famously was major factor in the nation’s victory in the Battle of Britain.

- Franz Bernheim (1899-1990), who brought the issue of Nazi discrimination in a petition to the League of Nations in 1933 from Upper Silesia, then part of Czechoslovakia, thus opening many eyes in the west to Nazi anti-Semitism

- Basil Liddell Hart (1895-1970), a British army captain who gained prominence as a military historian and military theorist between the two world wars, devising the defensive military strategy adopted by Neville Chamberlain

- Hans-Bernd Gisevius (1904-74), a major figure in the anti-Nazi resistance, a reliable chronicler of its activities, and one of its few survivors

These intriguing characters and a great many others come to life in the pages of The Nazi Menace. Hett reveals through the vignettes he writes about them how the runup to war with Nazi Germany was fraught with uncertainty.

How Neville Chamberlain viewed the coming war with Nazi Germany

As Hett explains it, Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain viewed the war he was convinced was coming with Nazi Germany through the lens of a three-fold strategy:

- The defensive posture advocated by military theorist Basil Liddell Hart. Britain’s fortunes would rise or fall with the success of the Royal Navy and the RAF. Britain would send no ground troops to the Continent.

- Rearmament, with special emphasis on the air force. The new Spitfire and, later, other superior fighter planes would help the island nation repel Germany’s bombers. The Chain Home network of radar stations around the coast would give Fighter Command early warning of any German attack. Meanwhile, Bomber Command would prepare to pulverize German cities.

- Appeasement would buy time for Britain to arm for war.

Reassessing Chamberlain’s strategy

Hett is unsparing in his assessment of Neville Chamberlain, whose authoritarian tendencies he clearly deplores. However, he writes, “we see the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939 as a vindication of Churchill’s long and lonely struggle against appeasement, and correspondingly, the final and damning verdict on Chamberlain’s policy. We see it this way because of the shocking outcome of 1940—the swift defeat of France—which we then assume to have been inevitable. But the dramatic Germany victory of 1940 was in fact a chancy, even unlikely outcome.”

“In the longer term,” Hett explains, “the Second World War provided a substantial vindication of most of Chamberlain’s strategy.” His emphasis on rearmament, especially in the air. The decision to minimize the role of the army. And a continuing insistence on keeping expenditures within bounds to maintain the health of the British economy.

Why blitzkrieg in the west wasn’t inevitable

As Hett explains, the blitzkrieg that won the day for Germany came about only because General Erich von Manstein went over the heads of his superiors in the OKW, or Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (the armed forces high command), and presented Hitler personally with the strategy they’d rejected. And even once adopted, the strategy might have failed. Heinz Guderian‘s Panzers broke through so dramatically in large part because the French defenses were poorly designed and both French and British generals stupidly fell into the cleverly conceived German trap that led to Dunkirk.

Hitler’s generals resisted an attack to the west for reasons that are lost on many observers today. In 1939, France’s army was widely regarded as the most formidable in the world. It was bigger than Germany’s, better trained on the whole, and it possessed more and better tanks. The top Nazi military brass feared a repeat of World War I. They fully expected a German offensive to bog down quickly, as had been the case in 1914. And that would guarantee a protracted war—which they knew Germany could not win. Even in 1939, most of the officers in the uppermost reaches of the OKW were convinced Hitler was mad and would lead their country to disaster.

The generals’ resistance to Hitler

In fact, Hett emphasizes the generals’ resistance to Hitler throughout The Nazi Menace. Few of the Wehrmacht’s top brass were ideologically driven Nazis. Nearly all viewed themselves as the heirs of the proud Prussian military tradition. From the earliest days of Hitler’s time in power, they resented taking orders from a mere corporal whose alleged military genius they ridiculed.

Two factions in the generals’ resistance

As Wikipedia notes—and Hett elaborates—the army’s Chief of Staff General Ludwig Beck (1880-1944), the Abwehr chief, Admiral Wilhelm Canaris (1887-1945) and the Foreign Office’s State Secretary, Baron Ernst von Weizsäcker (1882-1951) were the “anti-war” group in the German government, which was determined to avoid a war in 1938 that it felt Germany would lose. This group was not committed to the overthrow of the regime but was loosely allied to another, more radical group, the “anti-Nazi” fraction centered on Colonel Hans Oster (1887-1945) and Hans Bernd Gisevius (1904-74) which wanted to use the crisis as an excuse for executing a putsch to overthrow the Nazi regime.

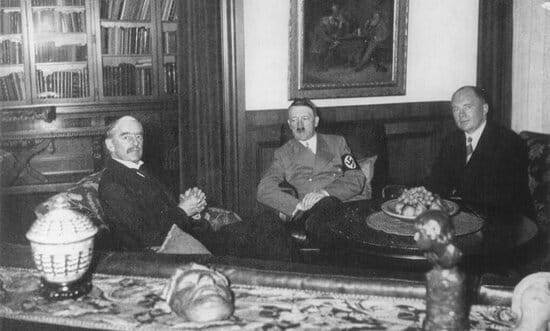

Chamberlain frustrated a coup attempt

But those five individuals were far from the only men in the upper echelons of the Nazi military establishment who turned against the Führer. And on at least one major occasion—in September 1938, when Hitler was moving toward an all-out invasion of Czechoslovakia—they were ready to launch a coup the moment he gave them the order. But Chamberlain unexpectedly intervened, frustrating both Hitler himself and them—Hitler, because he was forced to postpone the invasion, and the generals, because they regarded an unprovoked war as the only justification for their planned putsch. That Nazi Germany would wage war was no less certain. It would merely come a little later than Adolf Hitler wished.

The broader perspective

Hett views all these events in the prelude to World War II within the framework of the crisis of democracy—and he suggests a parallel in the broadest sense to the world of today.

The 1930s did, indeed, test the resilience of democracy. Much of Europe failed the test, with fascism taking firm hold in the nations that later formed the Axis and the weak democracies of central and eastern Europe crumbling in the face of Nazi aggression. Britain, too, was steadily drifting toward authoritarianism under Neville Chamberlain, who ruthlessly retaliated against his perceived enemies both within the Conservative Party and without. Only the United States truly met the test, as the New Deal restored hope for much of the public even though it was unsuccessful in delivering economic recovery until the nation rearmed in the face of war.

Is there truly a useful analogy between the 1930s and the present era? As Mark Twain is reputed to have said, “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes.” Certainly, there are echoes of the rhyme today, with authoritarian nationalist governments in place across the world, from Russia, Hungary, and Poland; to India and the Philippines, and arguably China as well; to Brazil and (until this month) the United States itself. But the forces do not appear to be lining up in any recognizable pattern. And perhaps we’ve turned the corner with the election of Joe Biden and the shift in power in the US Senate. Perhaps. In the end, democracy may firmly reassert itself once again. We can hope so.

About the author

Professor Benjamin Carter Hett teaches history at Hunter College and the Graduate Center of the City University of New York (CUNY). An earlier book, Burning the Reichstag: An Investigation into the Third Reich’s Enduring Mystery, was named the best book on Central European history in 2014. But he is best known for The Death of Democracy: Hitler’s Rise to Power and the Downfall of the Weimar Republic, which appeared in 2018. The Nazi Menace is the most recent of Hett’s four books to date.

For additional reading

Previously, I reviewed another of the author’s books, The Death of Democracy: Hitler’s Rise to Power and the Downfall of the Weimar Republic (How democracy died in Germany: is there a lesson for America today?).

You might also be interested in:

- 5 top nonfiction books about World War II (plus many runners-up)

- The 10 best novels about World War II (with 30+ runners-up)

- 7 common misconceptions about World War II

- The 10 most consequential events of World War II

- Top 20 popular books for understanding American history

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, plus a guide to this whole site, on the Home Page.