In the 19th century, as the nations of Europe rushed to grab ever-larger expanses of territory there, Africa was known as the Dark Continent. That label is still apt, but not for the same reason. Everywhere else—Europe, Asia, the Americas—understanding of Africa and Africans is limited, and far too often wildly distorted. It’s time to cast a little light into the darkness. This list of the 30 top books about Africa will help do that.

This post was updated on May 24, 2024.

Africa is richly diverse

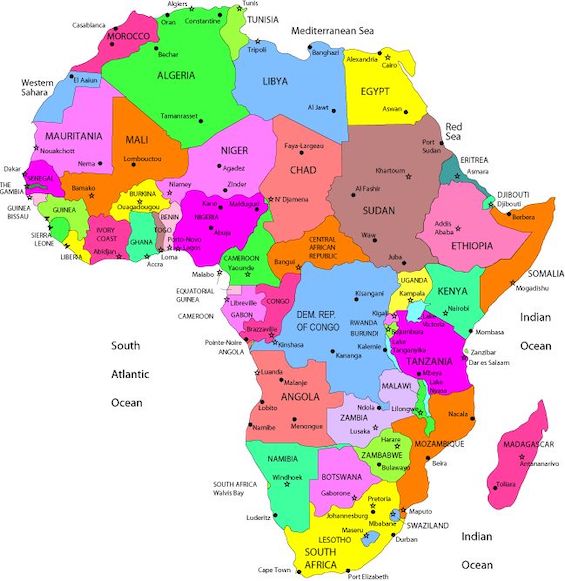

Africa today is a richly diverse place. Its ethnic mix, the more than 1,500 languages spoken there, and even the genetic origins of its 1.2 billion people are more varied than on any other place on Earth. Politically and economically, too, Africa is a patchwork, encompassing a wide range of political systems and economic realities. The continent—the world’s second largest by land area—houses 54 nations, from the predominantly Arab Mahgreb of the Mediterranean coast to the resource-rich lands of southern and western Africa. Half of the ten poorest countries in the world are African; six of the fifteen fastest-growing economies on the planet, including the top two, are in Africa, too. Yet, despite all this diversity, a shocking number of Americans still think of Africa as a single country.

The continent’s abundant literary riches

The West has long recognized the abundant literary riches in Africa. South African writers have been celebrated in Europe and the US for decades, from Alan Paton, Chinua Achebe, and Nadine Gordimer to Athol Fugard and J. M. Coetzee. (Two of them—Gordimer and Coetzee—have won the Nobel Prize for Literature.) Their Nigerian contemporaries, Chinua Achebe and Wole Soyinka, have received comparable praise; Achebe won the Man Booker Prize and Soyinka the Nobel Prize for Literature. But more recently attention has turned to younger, black African authors, including Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Ben Okri, and Yaa Gyasi.

Listed below you’ll find titles and capsule descriptions of the 30 top books about Africa in two lists: the top nonfiction books, and the top novels. I’ve recently read and reviewed nearly all these books; in each such case you’ll also see the review’s headline and a link. Each of the two lists is arranged in alphabetical order by the authors’ last names. I’ve awarded each title I’ve reviewed a rating of ★★★★☆ or ★★★★★ in each of the two lists. At the bottom, I’ve added a number of other books about Africa, including some with lower ratings.

A British perspective on writing about Africa

The big English newspaper The Telegraph publishes lists of the “best” books in many categories. One is the “10 Best Novels About Africa.” (It’s a great list, featuring both celebrated authors such as V.S. Naipaul, Nadine Gordimer, Doris Lessing, Naguib Mahfouz, and J. M. Coetzee; familiar contemporary names such as Alexander McCall Smith and Barbara Kingsolver; and African writers less well known to Americans.)

Top books about Africa: nonfiction

The Looting Machine: Warlords, Oligarchs, Corporations, Smugglers, and the Theft of Africa’s Wealth by Tom Burgis (2016) 354 pages ★★★★★ – Who’s responsible for corruption in Africa?

Misconceptions abound in the public perception of corruption in Africa. Tom Burgis’ incisive new analysis of corruption on the continent, The Looting Machine, dispels these dangerous myths. For starters, corruption is mistakenly believed to reign supreme in every country on the African continent. (There are 48 nations in Sub-Saharan Africa, with a combined population of more than 1.1 billion as of 2019.) Two Sub-Saharan African nations—Somalia and Southg Sudan—ranked lowest of the 179 countries in Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) as of 2019. But Syria, Yemen, Afghanistan, and Venezuela weren’t much better. Read more.

Portfolios of the Poor: How the World’s Poor Live on $2 a Day, by Daryl Collins, Jonathan Morduch, Stuart Rutherford, and Orlanda Ruthven (2009) 315 pages ★★★★☆ – Understanding the day-to-day reality of global poverty

Portfolios of the Poor reports the findings of a series of detailed, year-long studies of the day-to-day financial practices of some 250 families in India, Bangladesh, and South Africa, including both city-dwellers and villagers. The authors conducted monthly, face-to-face interviews with each family, focusing on money management and recording every penny spent, earned, or borrowed in “diaries” that formed the principal source for their observations. In the process, they made discoveries that may surprise you. Read more.

The Great Escape: Health, Wealth, and the Origins of Inequality, by Angus Deaton (2013) 362 pages ★★★★☆ – How the inequality gap came to be

A Nobel Prize-winning professor of economics and international affairs at Princeton explores inequality — between classes and between countries — with a detailed statistical analysis of trends in infant mortality, life expectancy, and income levels over the past 250 years. He concludes that the large-scale inequality that plagues policymakers and reformers alike in the present day is the result of the progress humanity has made since The Great Divergence (between “the West and the rest”) since the advent of the Industrial Revolution. “Economic growth,” Deaton asserts, “has been the engine of international income inequality.” (Deaton’s research backstops the work of today’s economics superstar, Thomas Piketty, who finds the data point to increasing inequality.) Read more.

The White Man’s Burden: Why the West’s Efforts to Aid the Rest Have Done So Much Ill and So Little Good, by William Easterly (2006) 443 pages ★★★★★

This is the best book that explores the ways and means of promoting economic development in poor countries, and it’s frequently included on any list of the top books about Africa. Easterly finds most traditional methods to be sorely lacking. The author, a former World Bank economist who is now an economics professor, emphasizes grassroots development. He writes about the necessity of involving people who will be affected by change in the process of planning and executing it — beginning with the selection of what is to be changed. A large proportion of Easterly’s experience and of the examples he cites come from sub-Saharan Africa.

The Tyranny of Experts: Economists, Dictators, and the Forgotten Rights of the Poor, by William Easterly – Why economic development happens (or doesn’t)

A decade after The White Man’s Burden, the author explores the history of economic development and finds that professionals in the field have gotten it all wrong. They present themselves as experts with technocratic solutions that suppress the rights of those they pretend to help — and almost invariably go awry. In fact, he asserts, democracy, rooted in local history and local customs, is the key to successful development. It’s a fascinating and surprising analysis and displays great insight. The book is widely regarded as one of the seminal accounts of development in Africa, and I agree. However, I read it before launching this blog so have not reviewed it. Read more.

Born in Blackness: Africa, Africans, and the Making of the Modern World, 1471 to the Second World War by Howard W. French (2021) 528 pages ★★★★★ — An eye-opening account of Africa’s pivotal role in world history

We’ve been taught that the modern world dawned when Christopher Columbus arrived in the Caribbean in 1492 in search of a route to the riches of “India.” In fact, for centuries, historians have been telling us that everything changed because explorers from Spain and Portugal set out across the unknown reaches of the seas to establish new trade routes to what we know today as China, Indonesia, and India. Without question, the ensuing Columbian Exchange played a large role in setting off the Great Divergence between East and West. But in Born in Blackness, a compelling new revisionist history, Howard W. French persuasively offers an alternative explanation about the origin of the shift.

“The first impetus for the Age of Discovery,” he writes, “was not Europe’s yearning for ties with Asia, as so many of us have been taught in grade school, but rather its centuries-old desire to forge trading ties with legendarily rich Black societies hidden away somewhere in the heart of ‘darkest’ West Africa.” Read more.

The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind: Creating Currents of Electricity and Hope, by William Kamkwamba and Bryan Mealer (2009) 292 pages ★★★★★ – A young man from Malawi points the way to hope for Africa

William Kamkwamba, the narrator of this awe-inspiring story, was a seventh-grade dropout who mastered fundamental physics by reading an out-of-date English textbook in a local, three-shelf library near his village. Using his new-found knowledge, he built a working windmill out of junkyard parts to generate electricity to irrigate his father’s farm. William Kamkwamba was 14 years old. Read more.

The Shadow of the Sun, by Ryszard Kapuscinski (2001) 325 pages ★★★★★ – How Africa came to be what it is today

The Shadow of the Sun is a treasure-chest of incisive reporting by a 27-year veteran of Africa about the continent’s recent past, featuring vivid and disturbing accounts of the antecedents of Liberia’s ghastly civil wars, the origins of the Rwandan genocide, and the roots of recurring famine in the nations of the Horn. Read more.

Cobalt Red: How the Blood of the Congo Powers Our Lives by Siddhartha Kara (2023) 288 pages ★★★★★—How our cell phones and electric cars depend on virtual slavery

Cobalt is primarily used in lithium-ion batteries—for cell phone and electric vehicle batteries—as well as in the manufacture of high-strength alloys. And half of the world’s reserves of cobalt lie in the DRC, where it is usually mined as a byproduct of copper and nickel. There, enormous commercial mining companies, most of them Chinese, tear up the Earth at large-scale facilities. And a third or more of the cobalt mined in the Congo is torn from the earth by hand by so-called “artisanal miners” trapped in modern-day slavery. Most of them are children. Read more.

The Idealist: Jeffrey Sachs and the Quest to End Poverty, by Nina Munk (2013) 274 pages ★★★★★ – The quest to end poverty: Jeffrey Sachs unmasked

Though commercial trade is far and away the dominant feature of the economic relationship between Africa and the so-called West, most of the attention in the new media tends to focus on aid — the decades-long project of the world’s richest nations to end poverty on the continent. Economist Jeffrey Sachs’s ill-advised and egregiously expensive Millennium Villages Project stands out as a symbol of just how badly wrong those efforts have gone. Read more.

The Bright Continent: Breaking Rules and Making Change in Modern Africa by Dayo Olopade (2014) 418 pages ★★★★★ — An optimistic view of economic development in Africa

Few who follow news from abroad can fail to have noticed that economic development has accelerated in many sub-Saharan-African countries in recent years. This book catalogs an impressive number of innovative businesses, social sector ventures, and even an occasional government initiative that contribute to the fast growth of this long-underestimated region — and explains the cultural norms that make innovation so natural for Africans. Read more.

It’s Our Turn to Eat: The Story of a Kenyan Whistle-Blower, by Michaela Wrong (2009) 372 pages ★★★★☆

No view of contemporary sub-Saharan Africa is complete without taking official corruption into account. This story, which focuses on one courageous Kenyan man who tried to expose some of the most blatant examples of embezzlement by senior government officials, brings to light the complexity of the issue and its impact on African society. It’s a profoundly discouraging story for anyone like me, who has known and loved Kenya and Kenyans and regarded it as one of the bright spots in a dark neighborhood.(Note: I read this book before launching this blog and thus have not reviewed it here.

Do Not Disturb: The Story of a Political Murder and an African Regime Gone Bad by Michela Wrong (2021) 464 pages ★★★★★ – Why does the West support an African regime gone bad?

A generation of diplomats, international bureaucrats, aid officials, and philanthropists have poured billions into the regime of Rwandan President Paul Kagame, often characterizing him as a “benevolent dictator.” But Kagame is no philosopher king. The economic statistics are inflated. And the 250,000 bodies in the Kigali Genocide Memorial are all Tutsis like the President and nearly everyone else in his regime. They do not include any of the hundreds of thousands of Hutus that Kagame’s army murdered in revenge when they liberated the country from the génocidaires. It all comes to light in veteran foreign correspondent Michela Wrong’s shocking exposé, Do Not Disturb: The Story of a Political Murder and an African Regime Gone Bad. Read more.

Top books about Africa: novels

River Spirit by Leila Aboulela (2023) 320 pages ★★★★☆ – A slave’s story set in colonial Sudan

Nearly a century and a half ago, the northern African nation of Sudan was in turmoil. Like much of the Middle East and North Africa, the people of the country were restive under the increasingly weak rule of the Ottoman Empire. The Khedive of Egypt, who administered Sudan for the sultan in Istanbul, appointed a famous British general, Charles Gordon, as governor-general to stifle the opposition. But during his time in office, a messianic Islamic leader calling himself the Mahdi spearheaded an anti-colonial revolt. And as these grand events played out, a young enslaved woman named Akuany experienced the disruptions and privations of the time. Sudanese author Leila Aboulela movingly tells her story in River Spirit. Read more.

A Spell of Good Things by Ayọ̀bámi Adébáyọ̀ (2023) 352 pages ★★★★☆ – Tragedy strikes two families in Nigeria today

Wuraola is the daughter of a wealthy and privileged medical family in a major provincial Nigerian town. She’s now in her first year of practice as a physician. Her mother, a physician herself, is pressuring her to marry because she is nearing thirty. And Wuraola is, in fact, in love with Kunle, the son of a rising politician. Her parents approve of him because his family is socially prominent and wealthy like them. But she’s just not quite sure she’s ready to give up the freedom that her independence affords her. For any outsider, this might appear to be a trivial problem for a woman with so many advantages in life. But, as we will see, it’s anything but that. Because the tragedy that will strike Wuraola stems from just one of many ugly problems besetting Nigeria today. And Ayobami Adebayo’s moving novel, A Spell of Good Things, brings those problems to light in an artful fashion. Read more.

Half of a Yellow Sun, by Chimanada Ngozi Adichie (2008) 562 pages ★★★★★ – Love, loss, and war in post-independence Africa

Half of a Yellow Sun movingly recounts the events of the 1960s that culminated in the lopsided Biafran war of independence (1967-70) that pitted the ill-equipped Igbo (Ibo) people of southeastern Nigeria against the massive forces of their national government, actively backed by the British. Read more.

Americanah by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie (2014) 610 pages ★★★★★ – Race, without blinders on

Following up her extraordinary novel about the Biafran war of independence, Half of a Yellow Sun (reviewed here), with an even more personal story, Adichie tells the story of Ifemelu, a young Nigerian who emigrates to the United States to complete her education and returns to Nigeria thirteen years later. Americanah — the word appears to be Nigerian slang for a person like Ifemelu who returns home with American habits and expectations — is, above all, a love story. The focus throughout is on her relationships with men — from her high school sweetheart to the “rich white hunk” to the African-American professor. Read more.

Radiance of Tomorrow by Ishmael Beah (2014) 257 pages ★★★★★ – Hope lives on in the depths of hell

Beah tells the story of several inhabitants of a small town called Imperi in the African nation of Lion Mountain (Sierra Leone) after they return home following a long, horrific civil war that has taken so many of the members of their family, their neighbors, and friends. This novel encompasses a wide range of African experiences during the period following decolonization, conveying the terror, the injustice, and the disappointment as well as the optimism that swept throughout the region below the Sahara over the past half-century. Read this book, and you’ll gain a foothold on understanding life in Sub-Saharan Africa. Read more.

Running the Rift, by Naomi Benaron (2012) 400 pages ★★★★★ – A brilliant novel of love, hope, and the Rwanda genocide

The Rwanda genocide is the central event in Running the Rift, a remarkable novel that tells the story of a young Tutsi man, Nkuba Jean Patrick, a supremely talented runner who aspires to compete in the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta. Read more.

The Mandela Plot by Kenneth Bonert (2018) 481 pages ★★★★★ – A gripping novel about the anti-apartheid struggle

If you’re under age 40 or so, the anti-apartheid struggle in South Africa from the 1950s to the 1990s probably seems like ancient history. But to those of us who lived through those times and followed the news with interest, the South African story loomed large. Nelson Mandela was, simply, the most famous person in the world in the 1980s and 90s, and almost certainly the most widely admired. His release from prison after 27 years in February 1990 was witnessed on television by a global audience comparable to that of the World Cup Finals. Mandela’s election as South Africa’s first Black president was celebrated around the world. Read more.

The Promise by Damon Galgut (2021) 256 pages ★★★★★ – A South African saga spanning four decades

As Rachel Swart lies dying in 1986 after a long bout with cancer, she coaxes a promise from her husband, Manie. He agrees to deed to their long-suffering Black house servant, Salome, the house she’s been living in all her life. Their younger daughter, Amor, overhears the exchange and presses her father at the funeral to fulfill the promise. But he denies having made it. As the title of Damon Galgut’s South African saga, The Promise, suggests, this conflict is the central thread in a story that will span four decades. And it symbolizes the dominant fault line in South African society as it emerges from apartheid less than a decade later. Read more.

The Death of Rex Nhongo by C. B. George (2016) 321 pages ★★★★☆ – A satisfying thriller set in Zimbabwe

A complex plot lies at the heart of The Death of Rex Nhongo. The complement of principal characters includes two expatriate families, one British, the other American, as well as an extended Zimbabwean family and a thug who works for the Central Intelligence Organization that terrifies the populace. The author skillfully draws together their numerous individual stories in a series of intersections that climax in a satisfying conclusion. The action takes place after the death noted in the book’s title, though the story manages to come full circle in the end. Naturally, the plot is contrived, but it’s a satisfying read. Read more.

After Lives by Abdulrazak Gurnah (2022) 316 pages ★★★★☆ — A Nobel Prizewinner probes his country’s history

After Lives is a multigenerational saga that follows the intertwined lives of several young people living in German East Africa. We follow them and their descendants for six decades and more. Through the colonial wars of the early 20th century. The First World War. Under the British in the 1920s. The Great Depression and the Second World War. And through the post-war years to the time of Tanzanian independence. In telling this story, Gurnah illuminates the contrasting approaches to colonization of the Germans and British, the fighting on the East African front in World War I, and the complex interrelationships among the region’s diverse peoples. Read more

Homegoing, by Yaa Gyasi (2016) 313 pages ★★★★★ – African Roots through African eyes

Yaa Gyasi’s extraordinary debut novel, Homegoing, traces the story of a Ghanaian family over more than two centuries through the lives of two branches of its descendants, one in Ghana, the other in the United States. The book opens in the mid-eighteenth century, when the slave trade was at its peak, follows the rollercoaster fortunes of the family through the turbulent years of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and concludes in present-day Ghana. Read more.

The Hairdresser of Harare by Tendai Huchu (2015) 200 pages ★★★★★ – Zimbabwe through the eyes of a single mother

You can read a dozen nonfiction books about Zimbabwe under Robert Mugabe’s kleptocracy and fail to get a more vivid sense of what life is really like there than from this recent novel by Tendai Huchu. In one short work of fiction, Huchu conjures up the sad reality of day-to-day existence in that beleaguered country: the 90 percent unemployment, the ubiquitous corruption, the hyperinflation, the ever-present shortages, the barely functional electricity service, the vicious eviction of white Africans from their farms and businesses, the rabid homophobia. Read more.

The Poisonwood Bible by Barbara Kingsolver (1998) 579 pages ★★★★★ — A brilliant novel explores the legacy of colonialism in the Congo

Some of the greatest works of literature in the 20th century addressed the theme of colonialism. Things Fall Apart by China Achebe. Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. The Wretched of the Earth by Franz Fanon. And E. M. Forster’s A Passage to India. There are many more. The Poisonwood Bible by Barbara Kingsolver isn’t routinely listed among them. But it should be. Although much of the action takes place after the Belgians have granted independence to the country, the book is all about the terrible, lingering effects of colonialism in the Congo. Written in gorgeous prose and firmly rooted in the tragic events of the early 1960s, the novel stands in testimony to the price paid by millions for the greed and racism of the white Europeans who plundered their land.

The story begins as Baptist missionary Nathan Price, his wife, Orleanna, and their four daughters settle in a Congolese village in 1959. Price has come to save souls, but the people of Kilanga alternately find his preaching to be either insulting or impossible to understand. They have their own religion, after all. In rotating chapters, the five women of the family narrate the action that unfolds over the ensuing years. As they struggle to survive in the unfamiliar and dangerous environment of tropical Africa, events quickly spin out of control in the huge, wealthy country around them. Read more.

How Beautiful We Were by Imbolo Mbue (2021) 384 pages ★★★★★—Ecological catastrophe strikes an African village

Welcome to Kosawa. A village nestled in a lush valley somewhere in West Africa, Kosawa suffers from the singular ill fortune of sitting atop an oil field. For as long as the village elders can remember, ever since independence, an American oil company named Pexton has been tapping the oil. And although the villagers felt no effects for several years, toxic waste began despoiling the river and polluting their land once Pexton opened a new well. Now, years later, pipeline leaks and continuing runoff from the wells poison their lives. Crops are shriveling and children are dying although Pexton has sent “experts” who insist there’s nothing wrong with the water. It is long past time for someone to do something. But it’s a madman who will lead the way. This is the set-up in Imbolo Mbue’s eloquent lament about environmental devastation and latter-day colonialism, How Beautiful We Were. Read the review.

A Bend in the River by V. S. Naipaul (1979) 290 pages ★★★★☆ — Nobel Prizewinner paints an unflattering picture of Africa

In 1960, the chief of staff of the army in the recently independent Belgian Congo led a coup that toppled the democratically elected government of Patrice Lumumba. Five years later he ousted the men he had installed in power and became the country’s dictator. His name was Mobutu Sese Seko. He remained in power until 1997, diverting somewhere between $4 billion and $15 billion in government funds into offshore accounts. His regime was notorious for corruption and human rights abuses. And that unflattering picture of Africa provides the backdrop to Nobel Prizewinner V. S. Naipaul’s celebrated story of the continent in the wake of colonization, A Bend in the River. Read more.

A History of Burning by Janika Oza (2023) 400 pages ★★★★☆ — A multigenerational tale of the Indian diaspora in Africa

Some three million people of Indian origin live today in the nations of southeast Africa. Although trade and migration between India and Africa reach as far back as the first millennium, much larger numbers arrived there late in the nineteenth century as indentured laborers under the British. One of the largest groups of Indian migrants—some 32,000 all told—came to work on the Kenya-Uganda Railway from 1896 to 1901. Pirbhai, the protagonist of this Indian diaspora novel, was among them.

Having been dragooned by British agents in his native Gujarat, he found himself in virtual slavery working under perilous conditions, surviving only by his wits. Unlike most of his fellow laborers, he stayed after escaping the terrors of the jungle—and eventually founded the family whose story Indo-Canadian author Janika Oza tells so well in A History of Burning. Read more.

The Seersucker Whipsaw by Ross Thomas (1992) 208 pages ★★★★★ – A terrific novel for political junkies about Africa

An American campaign manager receives an immoderate sum of money to help elect a Big Man as president of a country resembling Nigeria. He’s a genius at dirty tricks—and the candidate’s advisers prove to be equally flexible about campaign ethics. For anyone with even the most casual experience in electoral politics, the ensuing campaign is a wonder to behold. Read more.

Cutting for Stone by Abraham Verghese (2009) 667 pages ★★★★★—A deeply affecting medical drama set in Ethiopia

Marion Stone is a general surgeon at a charity hospital in New York City, and this is his story. It’s a story of war, revolution, and painful separations, but equally a tale of compassion, love, and the power of life-saving surgery. Born of Indian parents and raised in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, Marion now practices the skills he learned from his adoptive parents. Both are physicians, as is his father, a world-class surgeon who abandoned him at birth. Marion has become an American. but unwillingly so. Because the betrayal of the woman he loved had forced him to leave Ethiopia. This is Cutting for Stone by Abraham Verghese, a story of surgery in action. It’s a novel of exceptional power and beauty. Read more.

More top books about Africa

In addition to these top 20 books about Africa, here are several others, including both nonfiction and fiction. I’ve inserted links to my reviews for those I read recently enough.

- In Their Own Hands: How Savings Groups Are Revolutionizing Development, by Jeffrey Ashe with Kyla Jagger Neilan

- My Sister the Serial Killer by Oyinkan Braithwaite

- A Farewell to Alms: A Brief Economic History of the World, by Gregory Clark

- Embassy Wife by Katie Crouch

- Long Time Coming by Robert Goddard

- The African Equation, by Yasmina Khadra

- A Treacherous Paradise, by Henning Mankell

- The Missing American (Emma Djan #1) by Kwei Quartey

- Sleep Well, My Lady – Emma Djan #2 by Kwei Quartey

- Wife of the Gods (Darko Dawson #1) by Kwei Quartey

- Children of the Street (Darko Dawson #2) by Kwei Quartey

- Murder at Cape Three Points (Darko Dawson #3) by Kwei Quartey

- Precious and Grace (No. 1 Ladies Detective Agency #17) by Alexander McCall Smith

- The Double Comfort Safari Club (#1 Ladies Detective Agency #11) by Alexander McCall Smith

- Nairobi Heat by Mukoma Wa Ngugi

- Assegai by Wilbur Smith

- Dead Aid: Why Aid is Not Working and How There Is a Better Way for Africa, by Dambisa Moyo

For related reading

After viewing this list of 20 top books about Africa, you might also be interested in:

- 20 top nonfiction books about history

- Top 10 historical mysteries and thrillers

- 20 most enlightening historical novels

And you can always find all the latest books I’ve read and reviewed, as well as my most popular posts, on the Home Page.

Many thanks for this list. I live in Malawi and have read about half these books and they’re excellent.. it’s encouraged me to read the other half of your suggestion!

Glad to hear it. Thanks for writing.