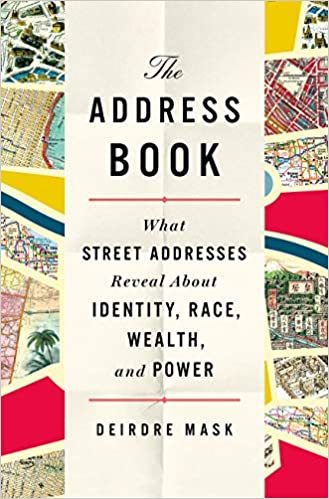

So, it turns out that street names and house numbers are a pretty big deal. We’ve only got them because of the troubled and sometimes violent circumstances that brought them into being. In fact, we tend to be ignorant of what addresses really mean. And while those of us who have addresses take them for granted, hundreds of millions of other people encounter endless problems because they lack them. But it’s not easy at all to get an address if you don’t have one—even if you’ve got a home. And that’s the entertaining and revealing story Deirdre Mask tells so well in The Address Book. In fewer than three hundred pages of text, Mask explores the history of street addresses through the lens of economic development, politics, race, class, and status. This is popular history viewed from left field, and it’s a pleasure to read.

The Address Book: What Street Addresses Reveal About Identity, Race, Wealth, and Power by Deirdre Mask. (2020) 336 pages @@@@@ (5 out of 5)

What addresses really mean

Addresses are so integral to most of our lives in the world’s towns and cities that we’re oblivious to their importance. But local government officials know better. For example, writes Mask, “in some years, more than 40 percent of all local laws passed by the New York City Council have been street name changes.” And that fact gives just a hint of what addresses really mean. And they mean a lot:

In economic development

Addresses “are one of the cheapest ways to lift people out of poverty, facilitating access to credit, voting rights, and worldwide markets.” It’s not just the homeless who lack addresses. That’s the case, too, for hundreds of millions of people who live in the world’s townships, barrios, and favelas. “Without an address, it’s nearly impossible to get a bank account. And without a bank account, you can’t save money, borrow money, or receive a state pension.” Mask reports on efforts underway throughout the Global South to address the problem, providing slum-dwellers with addresses using clever new technology.

In public health

“Addresses made pinpointing disease possible. . . Location and disease are inseparable for epidemiologists.” The COVID pandemic raging today has brought this reality into high relief, as public health officials struggle to track down, trace, and isolate the disease among the homeless in American cities. So, what addresses really mean can mean the difference between life and death.

For government services

“Addresses aren’t just for emergency services. They also exist so people can find you, police you, tax you.” Which is precisely why addresses came into being in the first place, probably in eighteenth century Europe. And that’s a fascinating tale in its own right—a story Mask tells with considerable skill.

Symbolizing social status

Mask’s subtitle is “What Street Addresses Reveal About Identity, Race, Wealth, and Power.” And she makes the case adroitly.

- Some researchers have found that American streets named after Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. tend to be found in economically depressed African-American neighborhoods.

- “Around the world,” Mask writes, “revolutionary governments kick off their regimes by changing the street names. Mexico City has more than five hundred streets named after Emiliano Zapata, the leader of its peasant revolution.” And the Soviet Union didn’t just rename the cities (Leningrad, Stalingrad) after its revolutionary leaders, it changed thousands of street names as well.

- “In Croatia, the main street of Vukovar . . . changed names six times in the twentieth century, once with each change of state.”

- And “as Jews disappeared from Germany, they were also disappearing from the street signs.”

Incidentally, “numbered streets are a largely American phenomenon. Today, every American city with more than a half million people has numerical street names. (Most have lettered streets, too.)” Which means, of course, with numbers and letters it’s tough to tell what the addresses really might mean. Elsewhere in the world, streets are almost always named—if, in fact, they can be identified at all. (Just try figuring out what’s a street and what isn’t in a teeming Kolkata or Lima slum.)

And, by the way, we know that widespread resistance to wearing masks in the current COVID pandemic is not a new thing. The same happened in 1917-20 in the lethal influenza pandemic that killed some fifty to one hundred million people. But there’s a parallel to house numbers, too: when European officials first started painting numbers on houses in the eighteenth century, they caused riots.

About the author

Deirdre Mask graduated from Harvard College summa cum laude and attended the University of Oxford before returning to Harvard for law school, where she was the editor of the Harvard Law Review. She has taught at Harvard and the London School of Economics. Mask completed a master’s in writing at the National University of Ireland. Her work has been published in numerous leading magazines. She lives with her husband and daughters in London. The Address Book is her first book.

For further reading

For my review of a book on a closely related subject, see Neither Snow Nor Rain: A History of the United States Postal Service by Devin Leonard (An entertaining history of the post office).

You might also check out other books that view history through the lens of a particular idea or commodity:

- The World in a Grain: The Story of Sand and How It Transformed Civilization by Vince Beiser (We never think about it, but our civilization is built on sand)

- Empire of Cotton: A Global History by Sven Beckert (Capitalism reexamined from an historical perspective)

- Paper: Paging Through History by Mark Kurlansky (More than you ever wanted to know about the history of paper)

Perhaps you would also be interested in 20 top nonfiction books about history plus more than 80 other good ones or even 10 best alternate history novels reviewed here.

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, plus a guide to this whole site, on the Home Page.