Back in 1996, a book entitled The Millionaire Next Door by Thomas J. Stanley and William D. Danko hit the bestseller lists. The two authors demonstrated that owning a small business such as a dry cleaners or a neighborhood grocery, for example, might over time make its frugal owners into “millionaires.” The term “top 1%” wasn’t yet in common use, but the implication was those people qualified. Stanley and Danko seemed to mean that anyone who had accumulated assets totaling more than $1 million was therefore a millionaire and rich. But how naive we were to think such a thing!

Estimated reading time: 12 minutes

The top 1% isn’t who you think

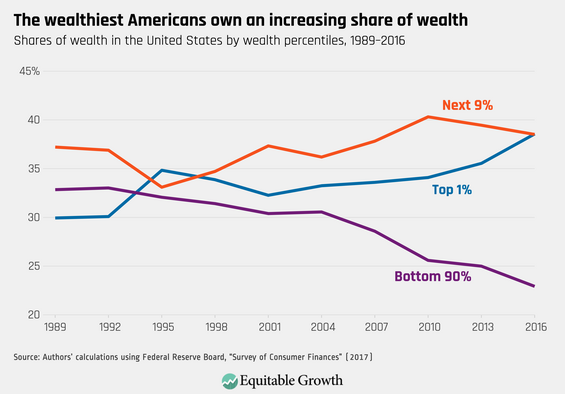

Today, holding assets of $1 million doesn’t even qualify an American for the top 10% financially, let alone the top 1%. That requires a minimum of $11 million in assets. In 2018, there was a total of 539,000 US households with an income of more than one $1 million per year. They numbered about 0.3% of the American population. But the real wealth in our society is in the hands of the top 0.001%—and those people, we learn in Michael Mechanic’s fascinating new book, Jackpot, are rich beyond comprehension. As of 2020, it took at least $2.1 billion to make the cut for the Forbes 400. And collectively those 400 households possessed a total of $3.2 trillion.

Who’s really, really rich today

For a reality check, tune into the Forbes Real-Time Billionaires List. Here are just the top five people—remember, these are people, not companies—on the list as of May 4, 2021.

| Rank | Name | Net Worth | Source | Country |

| 1 | Jeff Bezos | $193.2 billion | Amazon | USA |

| 2 | Bernard Arnault & family | $180.1 billion | LVMH | France |

| 3 | Elon Musk | $166.2 billion | Tesla, SpaceX | USA |

| 4 | Bill Gates | $130.4 billion | Microsoft | USA |

| 5 | Mark Zuckerberg | $115.4 billion | USA |

Note that, as I write, there are three other men, all Americans—Warren Buffet (Berkshire-Hathaway), Larry Ellison (Oracle), and Larry Page (Google)—with net worth north of $100 billion. These people aren’t just rich. Even filthy rich doesn’t begin to convey the power they possess through such unfathomable wealth. “Top 1%?” Hah!

Go to that Forbes site, and you’ll probably find the numbers, and perhaps even the rankings, are a little different. Much of what’s portrayed here is paper wealth, simply the reflection of current stock market values for companies such as Amazon, Tesla, Microsoft, and Facebook. The market’s volatility may inflate or deflate these fortunes, but they’re real nonetheless. Even 1% of Jeff Bezos’ $193.2 billion today would still be nearly two billion dollars. But, stock market volatility notwithstanding, it’s not just the rich who are getting richer, Mechanic points out. “The insanely rich are getting insanely richer.”

Yet when Michael Mechanic set out to convey what it’s like to be really, really rich in America today, he didn’t turn to these people. They’re virtually unreachable. He spoke instead with some of those who help them make more money or sell them goods and services. And he turned to those whom the centibillionaires might consider pikers. “When we hear the term ‘rich people,’ Mechanic writes, “we tend to think more about the top 0.1 percent, families with assets of $29.4 million and up,” or five times as much as the minimum to qualify for the top 1%. “This is the realm of elite private schools, private travel, stunning houses, extraordinary vacations (and vacation properties), luxury cars, and concierge doctors.” The United States, he reports, “boasts more than 32 percent”—over 90,000—of these ultra-high-net-worth people on the planet, even though we house only about 4% of the population.

Jackpot: How the Super-Rich Really Live—and How their Wealth Harms Us All by Michael Mechanic (2021) 415 pages ★★★★★

Pursuing “America’s jackpot winners”

In researching this book, Mechanic spent little time speaking with people in what Senator Bernie Sanders has called the “billionaire class.” (Mechanic sometimes refers to them as “America’s jackpot winners” or “the three-comma club.”) He gained insight on their lives through those who sell them $100 million houses or provide services such as security at $1.5 million per year, ultra-sophisticated financial management, philanthropic advice, and investigative dating services. He also consulted economists at UC Berkeley and Harvard researching extreme wealth. Little wonder. “With few exceptions,” he writes, “every time I reached out to someone worth more than a couple hundred million dollars, even when I had a trustworthy introduction, that person’s entourage intervened with pre-interviews and rejections.” But Mechanic did speak, sometimes in great depth, with a number of those he calls “ultra-wealthy.”

Living the life of the ultra-rich

In Jackpot, Mechanic strives to convey a sense of what it’s like to live the life of the ultra-rich, the top 0.1%. Multiple homes in exclusive neighborhoods scattered about the planet. Private jets, massive yachts, and fleets of hideously expensive automobiles. Ability to pick up the phone and call almost anyone on Earth. But he emphasizes, as do so many of his subjects, the downside as well. Ever-present need for security. Endless requests for money. Constant preoccupation with the management of investments even if the scutwork is delegated to armies of advisors. And the loss of connection with anyone outside their tiny, privileged class.

Insights from four remarkable individuals

Four individuals stand out among those the author interviewed for this book.

Jerry Fiddler

Entrepreneur Jerry Fiddler talks “about the rungs of the economic ladder being stretched so far apart that people can barely contemplate the next rung. ‘I think the public impression of the [top 1%] is really the 0.001 percent. . . I mean, they’re seeing Kochs and Buffetts and Gates. They’re seeing them as the 1 percent and they’re really not. The gap between me and them is probably larger in a lot of ways than between . . . most people and me.” And Fiddler has amassed a fortune that appears to be in the hundreds of millions. As he explains to the author, possessing a fortune enables him to command far larger returns from the market than are available to the average investor. “‘To take your entire asset base and grow it by 7 percent a year, very few people could do that. Whereas I probably could.” Centibillionaires most assuredly do so. But even most of those in the top 1% can’t do so. Because the hedge funds and other investment vehicles that earn such out-of-control returns often require $50 million, $100 million, or more as a minimum.

Tracy Gary

Philanthropic advisor Tracy Gary‘s “mother and stepfather amassed vast resources—hundreds of millions in today’s dollars. They had a private jet, a helicopter, a yellow Rolls-Royce, and estates in Florida, Minnesota, New York, Wisconsin, and Paris, each with its own staff.” But Tracy wants none of it. She is one of the most prolific philanthropic advisers in the business, having founded several organizations dedicated to redirecting resources toward addressing the problems of the poor. She “encourages her clients to give away as much of their money as they can stomach, but not to Stanford or Yale or other institutions with massive endowments: ‘Please diversify,’ she says, and give to social justice organizations.'”

Darren Walker

Ford Foundation President Darren Walker “grew up penniless in rural Texas and went on to become an icon in the world of philanthropy. As an African-American, he speaks with special insight into white privilege and regularly encounters “extraordinarily wealthy white men who are unwilling to acknowledge their advantages.” The stereotypical claim by America’s wealthiest is that they “worked hard for their money,” implying that people who are poor do not. And that, of course, is an ugly insult for the millions who work two or three jobs just to keep food on the table or pay the rent. And Walker notes how few rich Black people there are. “‘If we’re going to have a capitalist system, we should have one where the opportunity to reap the rewards are open to all. And we know our system has never been open. It was designed on the backs of slaves.'”

Nick Hanauer

Venture capitalist Nick Hanauer‘s Twitter profile declares that he is “NOT a billionaire.” Ultra-wealthy, to be sure, but with a fortune south of a billion. Top 1%? No. Most likely, the top 0.01%. And he’s critical of those who do command billions but abdicate their responsibility to society at large. As a consequence, he insists, the revolution isn’t coming in the future. It’s already here. “‘Trumpism is pitchforks. . . The dissolution of democratic norms. Increase in racism, xenophobia. The fundamental destabilization of society. The erosion of social cohesion. You’re experiencing it!'”

At the root of the inequality: greed

“Greed has always been one of the primary drivers of the American story,” Mechanic writes. “It fueled the genocide and seizure of land from Native Americans, made slavery a hereditary institution, and gave rise to our system of mass incarceration. It turned Florida from a malarial swamp into a vacation getaway during the 1920s, built the Las Vegas Strip, and compelled Wall Street wonks to invent the collateralized debt obligations and other opaque financial instruments that tanked the U.S. economy in 2008. . . It gave us Michael Milken and junk bonds, the dot-com boom, the Bitcoin roller coaster, Bernie Madoff, and the college admissions scandal.” And one way or another the system greed has forged will eventually come to an end.

A different perspective on wealth

I came across an intriguing article in the San Francisco Chronicle (May 15, 2021) entitled “What’s needed to feel wealthy in Bay Area?” by Kellie Hwang and Nami Sumida. (The article appeared online a day earlier under a slightly different title.) Here’s the gist of it: “Respondents to the 2021 Modern Wealth Survey from Charles Schwab said it takes an average net worth of $3.8 million to be wealthy in the Bay Area, down from $4.5 million in 2020. If you’re just aiming for “financial happiness,” that carries a price tag of $1.8 million in 2021, compared with $2.1 million in 2020. A mere $1.3 million is enough to make you “financially comfortable” in 2021, versus $1.5 million in 2020, according to the survey responses.” In other words, you don’t have to qualify for the top 1% to feel rich. Interesting, no? So, that 1996 book I wrote about above might not have been so far off the mark, after all. Even if Jeff Bezos’ net worth is 148,615 times as large as that $1.3 million.

Note that those numbers hold for the San Francisco Bay Area, which is by far the most expensive metro area in the country. In New York, for example, $997,000 would be enough to make a family “financially comfortable,” according to the Schwab survey.

About the author

It would appear that Michael Mechanic is not a member of the top 1%. From the author’s bio on the Mother Jones website: “Prior to MoJo, he was longtime managing editor for the weekly East Bay Express and a reporter and editor for other alt-weeklies and magazines, including the late Industry Standard. His writing has also appeared in the Atlantic, the Los Angeles Times, and Wired. He lives in Oakland with his wife and kids, a cat, a hedgehog, and too many musical instruments to master.” Jackpot is his first book.

However, according to the World Federation of Science Journalists, there’s more to Michael Mechanic. He “holds a master’s degree in cellular and developmental biology from Harvard and a master’s in journalism from UC Berkeley. He’s spent the past decade as a senior editor for Mother Jones, where he handles stories for both print and web, and writes occasionally on science and other topics. His latest piece involves an emerging dual-use technology known as gene drive. As a biochemistry major at Cal, he worked on synthesizing natural poisons from those tropical frogs people warn you not to lick because if you do you’ll go into histrionic convulsions and die.” (Yes, it’s the same person.)

For related reading

This is one of the Good books about billionaires.

Check out:

- The Lords of Creation: The History of America’s 1 Percent by Frederick Lewis Allen (Why the Great Recession happened—and the Great Depression before it)

- Winners Take All: The Elite Charade of Changing the World by Anand Giriharadas (Are tech billionaires and hedge-fund managers changing the world for the better?)

- Dark Money: The Hidden History of the Billionaires Behind the Rise of the Radical Right by Jane Mayer (How the Koch brothers are revolutionizing American politics)

- Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking of America by Kurt Andersen (How America lost its way and ended up at war with itself)

You might also enjoy Top 20 popular books for understanding American history.

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.