Estimated reading time: 6 minutes

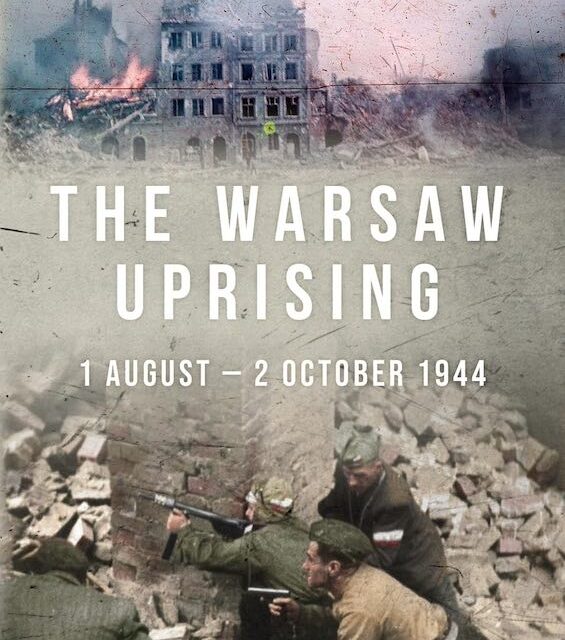

No country in the world suffered greater devastation in World War II than Poland, not even the Soviet Union, where as many as twenty-seven million people died. Poland’s six million dead represented an even higher proportion of the pre-war population—about one in five. And Poland’s cities lay in rubble. Yet the devastation was greater still in Warsaw, the site of two of the signal events of the war: the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising in the spring of 1943 and the Warsaw Uprising of 1944 by the Polish underground. Of the two, the events in the Ghetto have received far more attention. And in The Warsaw Uprising, 1 August to 2 October, 1944, George Bruce fills the gap with a moving, blow-by-blow account of that tragic episode in Polish history—the world’s “first example of full-scale urban guerrilla warfare.”

A large, organized underground army under civil authority

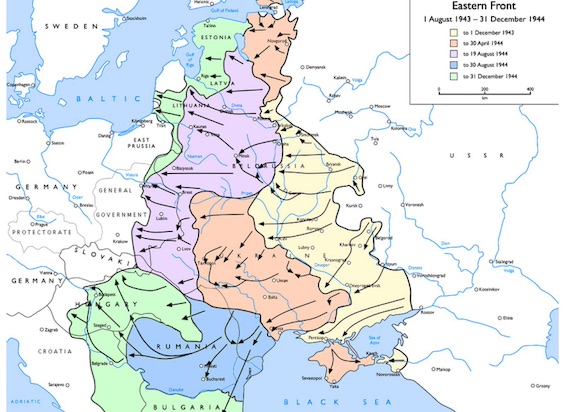

The Warsaw Uprising was no spontaneous event. It was the culmination of plans laid years earlier in the war by Europe’s best-organized and most powerful anti-Nazi partisan movement. While opposition to German occupation only gradually emerged in most countries, Poland’s underground began to form within two months of the Nazi invasion on September 1, 1939.

By the spring of 1940, the elements were in place: A Polish Government-in-Exile based first in Paris and later in London. A fighting force known as the Armia Krajowa (Home Army). And a secret civil authority answerable to London throughout both the German and the Russian occupation zones, both headquartered in Warsaw. “By the end of the year the secret underground state had taken first form in the Political Liaison Committee, made up of representatives of the three main parties.” But it was the Government-in-Exile that literally called the shots, with effective authority over the Home Army.

The Warsaw Uprising, 1 August to 2 October 1944 by George Bruce (2021) 339 pages ★★★★★

A sophisticated operation on the ground

Within months of the war’s outbreak, the newly organized government and army began to absorb most of the other partisan efforts that had sprung up around the country. (The principal exception was the People’s Army, the Communist partisan force.) The Home Army “was to be composed of provincial, regional, area, sector and outpost commands, with staffs, special diversionary-action platoons, and combat platoons situated in operational strongpoints. Outpost commanders could lead locally raised platoons. A platoon, about fifty men, was to be the basic organizational and tactical unit.” Partisans in other countries (with the possible exception of Yugoslavia) could only dream about building such a sophisticated organization.”

To a significant degree, the Home Army came to resemble the pre-war Polish Army. “Throughout Poland,” Bruce explains, “officer training schools were launched with primary courses lasting five months, each class consisting of between three and five officer-cadets. Courses were also set up for propaganda and information, communications, sabotage and motor engineering. Specialized training courses for women covered first aid, liaison, communications, weapons training and sabotage.”

Civilian volunteers played vital roles, too. “The manufacture of hand-grenades and other weapons was begun in secret underground workshops, laboriously burrowed out beneath city cellars,” Bruce writes. “A special section of artists and printers accurately forged false identity papers in a subterranean printing works excavated beneath the entrance hall of a Warsaw mansion.”

Leadership struggles in both London and Warsaw

General Władysław Sikorski became prime minister of the Polish Government-in-Exile and Commander-in-Chief of the Polish Armed Forces, and he proved to be supremely capable. In contrast to others in the Polish leadership, he accurately foresaw the need to maneuver carefully between the demands of London and Moscow. Because, eventually, he believed, the Red Army would be on Poland’s doorstep. Unfortunately, not all the other leaders appointed to build and manage the fast-proliferating resistance apparatus on the ground concurred with his assessment. Throughout the war, right-wing anti-Communist leaders struggled for supremacy over the more moderate men Sikorski favored. His tragic death in mid-1943 in an airplane crash, and the others’ inability to find common ground, would be the Home Army’s undoing.

Devastating losses

The author patiently describes the growth of the Home Army through the early years of the war. But the emphasis, of course, is on the events of 1944. His account of the fighting is detailed, as is his description of the ongoing leadership debates in London and Warsaw about how to deal with the Soviets. Of course, history tells us that the whole effort was in vain. Acting under Adolf Hitler’s direct order, the German army destroyed the city in the end and massacred most of its surviving inhabitants. Russian artillery contributed to the damage, but to a much lesser degree.

When the Soviets counted the bodies in 1945, it became clear that Hitler had had his way. Some eighty-five percent of the city’s pre-war buildings lay in ruins. And, as the National WW2 Museum tells us, “Polish losses during the uprising included 150,000 civilian deaths and about 20,000 Home Army casualties. The German forces lost an estimated 10,000 troops.” And, within months, Warsaw had become the capital of a Soviet satellite, yoked to the Communist state for more than forty years.

About the author

George Bruce seems not to exist. I can find absolutely no information about him or her anywhere online. Presumably, the name is a pseudonym for someone who wishes to remain anonymous. All I can deduce from the context is that whoever it is reads Polish and German as well as English and is intimately familiar with the geography of Warsaw.

For related reading

You’ll find this book in good company at 10 true-life accounts of anti-Nazi resistance. You may wish to check out in particular Poland Alone: Britain, SOE and the Collapse of the Polish Resistance,1944 by Jonathan Walker (The tragic story of the Polish Resistance).

You might also enjoy:

- 10 top nonfiction books about World War II

- Good books about the Holocaust

- 7 common misconceptions about World War II

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.