Estimated reading time: 6 minutes

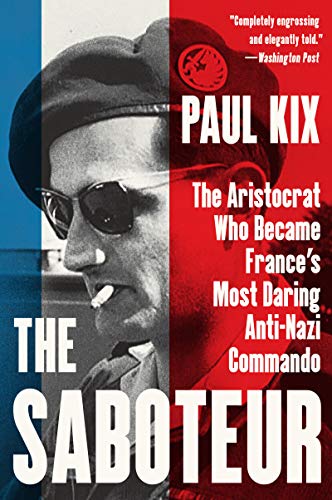

If you’d visited France anytime during the decades following World War II, you might have gotten the impression that all forty million French men and women had worked for the Resistance. In fact, studies have shown that only about two percent of the population (perhaps three quarters of a million) did so, and most of them in the closing months of the war. By contrast, an estimated twenty percent of France’s people collaborated with the Nazis. Yet some were indeed heroes. And one of the most interesting (if controversial) of those heroes was Robert de La Rochefoucauld, the subject of Paul Kix‘s The Saboteur: The Aristocrat Who Became France’s Most Daring Anti-Nazi Commando.

A thousand years of family history

For Americans, living in a country that’s been a nation for less than 250 years, it’s sometimes difficult to grasp the weight of history in Europe. Robert de La Rochefoucauld’s family traced its roots to the year 900, during the years when the nation of France emerged from Charlemagne‘s empire. One of his direct ancestors was the Duc de La Rochefoucauld who woke up Louis XVI in 1789 as the mob was closing in on the Bastille. The king asked him “if it was a revolt. ‘No, sire,’ he answered. ‘It is a revolution.'”

Later Rochefoucaulds were remembered in the pages of Proust. And throughout the centuries the men of the family continued to distinguish themselves, some of them in ways every French schoolchild may be aware of to this day. That was the weight of history on young Robert de La Rochefoucauld when, at sixteen in 1940, he fled with his family from their estate northeast of Paris to escape the fast-advancing Nazis.

The Saboteur: The Aristocrat Who Became France’s Most Daring Anti-Nazi Commando by Paul Kix (2019) 298 pages ★★★★☆

No penniless aristocrats, these

Unlike the stereotype of the penniless aristocrat, the La Rochefoucaulds were among the wealthiest families in France. Robert’s parents and many siblings lived in a forty-seven-room chateau set on thirty-five acres. His grandmother’s home was even bigger, and she owned a “private rail car—with four sleeper cabs, a lounge and dining room.” Yet for even the wealthiest in France the possibility of a comfortable life ended abruptly in May 1940 when Hitler’s Panzer divisions crashed through the Ardennes on a beeline to Paris. And for young Robert, the would be anti-Nazi commando, a patriot with all the passion of adolescence, that was unforgivable.

Nix relates how the sixteen-year-old, fueled by fury and determination, doggedly made his way through Spain to London to enlist in Charles de Gaulle‘s Free French.

An anti-Nazi commando up front and close with Charles de Gaulle

When Robert de La Rochefoucauld told his English handler that he’d come to London to enlist with Charles de Gaulle, he was surprised that the man simply gave him directions. What he didn’t know was that he had wandered into SOE’s Section R/F, the one department in the Special Operations Executive that collaborated closely with de Gaulle. And when at length he actually met the general, who had a fearsome reputation, he was surprised again to be given the green light to work with the British. De Gaulle had even been almost friendly.

However, as virtually everyone else who dealt with the man later testified, the general was a first class jerk. He was almost invariably rude to the point of obnoxiousness. And, as the New York Times reported in 2000, “Winston Churchill and Franklin D. Roosevelt plotted to remove Charles de Gaulle as leader of the French resistance at a critical moment in World War II, saying they found him boastful, conceited and deeply biased against Britain and the United States, according to newly released British records.” Neither Churchill nor Roosevelt liked or trusted the man.

The remarkable story of a young anti-Nazi commando

After extensive training in Britain in sabotage and self-defense, Robert de La Rochefoucauld parachuted into France in 1942 when he was not yet twenty years old. During the next three years he trained hundreds of his fellow Frenchmen in the use of explosives. Together, they destroyed countless miles of railroad track, blew up munitions dumps, and murdered hundreds of Nazi soldiers.

Meanwhile, the Germans and their French allies, acting through the Sicherheitsdienst (SD), Abwehr, SS, and French Milice, rolled up dozens of Resistance networks, one after another. Nazi interrogation techniques and their success in doubling enemy agents led to spectacular betrayals of French fighters. And de La Rochefoucauld was no exception. He was captured three times. After the first time, he endured months of prison and endless torture. But, when on his way to be executed, he pulled off a daring escape; he remained free for months afterward. The second time he was captured, men under his command freed him by murdering the German guards around him (and nearly killing him, too, in the process). The third time he escaped again. (That story alone is Hollywood material.) The typical life expectancy of an anti-Nazi commando was six months. De La Rochefoucauld survived five years of war.

Perspective on Britain’s Special Operations Executive

Shortly after the armistice that France’s Marshal Philippe Pétain signed with Adolf Hitler, Neville Chamberlain’s government in Britain secretly established the world’s first organized Special Forces, the Special Operations Executive. (Some authors mistakenly refer to the SOE as Winston Churchill’s brainchild, but the organization had its origins in the British bureaucracy in 1938, as Kix makes clear.) This was the organization de La Rochefoucauld joined in 1940. The agency’s mission was “to coordinate all action, by way of subversion and sabotage, against the enemy overseas.” And France was SOE’s highest strategic priority.

While other countries captured by the Nazis were managed by a single department, there were six for France. In fact, there were two operational sections for France, one that worked with Charles de Gaulle and the Free French, and one that didn’t. De La Rochefoucauld enlisted with the former. Most of the other books I’ve read about the role of SOE in the French Resistance are based on the work of the latter, Section F.

Given the fierce jealousy directed at SOE by the British military, Foreign Office, MI6, and MI5, the agency’s survival, or at least its independence, might seem baffling. The usual explanation is that Winston Churchill had forced SOE down their throats. However, in fact, the agency’s early successes made the case for its existence compelling. It “had already engineered two of the Allies’ biggest victories in the European theater. The first was the assassination of Reinhard Heydrich . . . [and] the second was the sabotage of the Norsk Hydro facility in Norway.”

For related reading

This book is one of 10 true-life accounts of anti-Nazi resistance.

Check out Good books about the French Resistance, which includes nine other books on the topic.

You might also be interested in:

- 10 top nonfiction books about World War II

- The 10 best novels about World War II

- 20 top nonfiction books about history

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.