Estimated reading time: 7 minutes

What most of us in the US know about Cuba revolves around three events. The Spanish-American War (“Remember the Maine” and Teddy Roosevelt’s Rough Riders). The Bay of Pigs Invasion. And the Cuban Missile Crisis. But our two countries have a much longer and richer history than that. In fact, as historian Ada Ferrer illustrates so brilliantly in Cuba: An American History, the affairs of Cuba and the United States have been intertwined ever since President Thomas Jefferson envisioned adding Cuba as the seventeenth state. And Jefferson was just the first of many among the nineteenth century’s twenty-two Presidents to fantasize about incorporating the island into the Union. In fact, the last of them launched the war with Spain with something very much like that in mind. But it was only the start of another century of shared Cuban-American history that kept the two nations locked in each other’s arms.

Dueling perspectives on a shared history

Observers in the United States and Cuba harbor dueling interpretations of that shared history. For example, US schoolbooks portray William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt’s war as an effort to liberate Cuba from Spanish tyranny. By contrast, the Cuban people typically view the event as a naked imperial land grab. In 1898, when the war started, Cuban insurgents were already close to toppling Spain’s colonial regime. Then the US Army walked in, took the credit for the victory, and proceeded to occupy the country for several years. And the US intervened repeatedly over the next three decades when Cuban officials threatened North American commercial interests. So, if you wonder why many Cubans hate the United States, a big part of the explanation lies in that long-ago history.

Cuba: An American History by Ada Ferrer (2021) 576 pages ★★★★★

Winner of the Bancroft Prize and the Pulitzer Prize for History

Cuban sovereignty seemed up for grabs

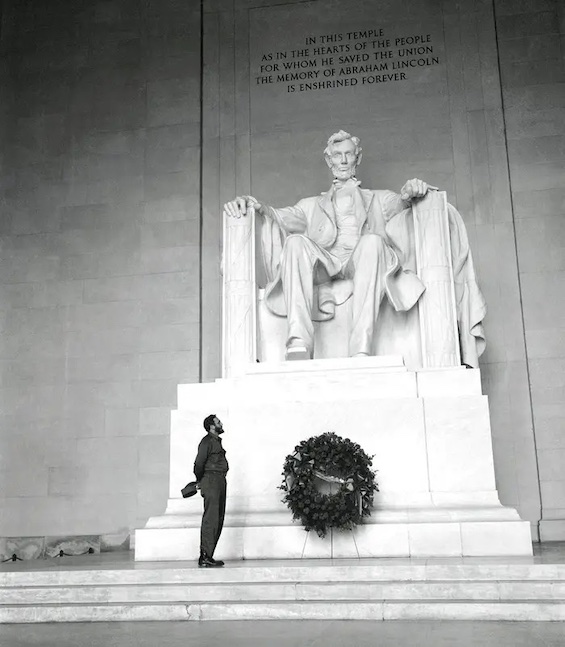

As Ferrer makes abundantly clear, there is no way to write a history of Cuba without close attention to the influence of the United States. But in Cuba: An American History, she also relates how large the island has loomed in US domestic politics. Until the election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860, every US President, ten of them slaveholders, looked on Cuba for its potential to become two or three new slave states, thus strengthening the hand of the South in Congress and the Electoral College. Because, like the South, Cuba’s was a slave-based economy, dominated by African slaves working on the island’s sprawling sugar plantations (many of them owned by North Americans). And, even though fantasies of incorporating Cuba into the United States no longer surfaced in Congress or the White House, Cuban sovereignty was an illusion.

Cuba’s little-known role in the American Revolution

Cuba was far more than a bystander in North American affairs, even before our independence was assured. “The famous battle of Yorktown in October 1781, for example, was financed in large part by Cuban funds arriving at a critical moment. At the time, Washington’s troops were penniless and demoralized. There was money neither to pay nor feed them, and major mutinies had already broken out several times that year. The French troops fighting alongside the Americans under the Comte de Rochambeau were also suffering and out of money.” It’s no exaggeration to say that Cuba’s financial assistance was a major factor in the victory.

But Yorktown was far from the end of the help that flowed north from Cuba. “Trade between the island and the thirteen colonies flourished in the early 1780s. . . The trade was important on its own, but it was also a major source of silver currency for the American Revolution and, increasingly, for the Bank of North America, the new republic’s first central bank.”

A century of interventions from the north

In the view expressed in the US National Archives, “Approved on May 22, 1903, the Platt Amendment was a treaty between the U.S. and Cuba that attempted to protect Cuba’s independence from foreign intervention.” But the Platt Amendment was nothing of the sort in reality. Coming on the heels of the war with Spain, it was expressly designed to permit the United States to intervene at will, with military force if necessary, to overturn policies or the results of Cuban elections that US officials deemed a threat to the interests of landowners and investors based in New York, Chicago, Miami, and other US cities.

The US did indeed reoccupy Cuba three times in the following twenty years (1906–09, 1912, and 1917–22). Only FDR’s reluctance to intervene stopped the pattern. But those investors from the north rested easily, anyway, as pro-American Cuban strongman Fulgencio Batista soon rose to power. He lasted for about two decades. Then came the Cuban Revolution, the Bay of Pigs—and the threat of all-out invasion by US troops in the Cuban Missile Crisis. But even that wasn’t the end of it. The US embargo of Cuba persists to this day, crippling the Cuban economy. And Cuban exiles in southern Florida, overwhelmingly right-wing and Republican, continue to wield enough influence to prevent the end of the embargo.

About the author

Ada Ferrer holds an endowed chair in History and Latin American Studies at New York University. For Cuba: An American History, her third book on the island’s history, she won both the Pulitzer Prize for History and the Bancroft Prize, the discipline’s most prestigious award. She describes the book as “a product of more than thirty years of work and of a lifetime of shifting perspectives between the country where I was born and the country where I made my life.” Both her other books also won literary awards.

Ferrer, who is Cuban-American, was born on the island between the Bay of Pigs in 1961 and the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962 but moved with her mother to the United States very shortly afterward. She holds an AB degree in English from Vassar College (1984), an MA degree in history from University of Texas at Austin (1988), and a PhD in history from the University of Michigan (1995).

For related reading

You’ll find this book in good company at:

- Top 20 popular books for understanding American history

- 20 top nonfiction books about history

- Top 10 nonfiction books about politics

- Good books about racism

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.