Estimated reading time: 6 minutes

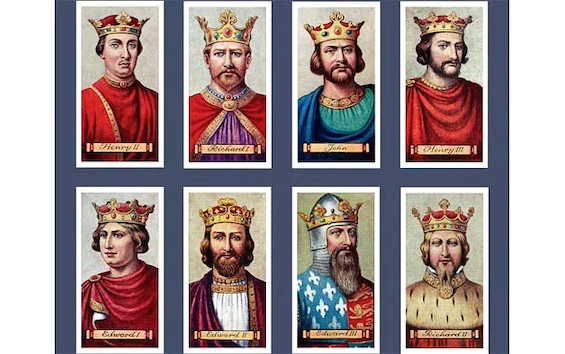

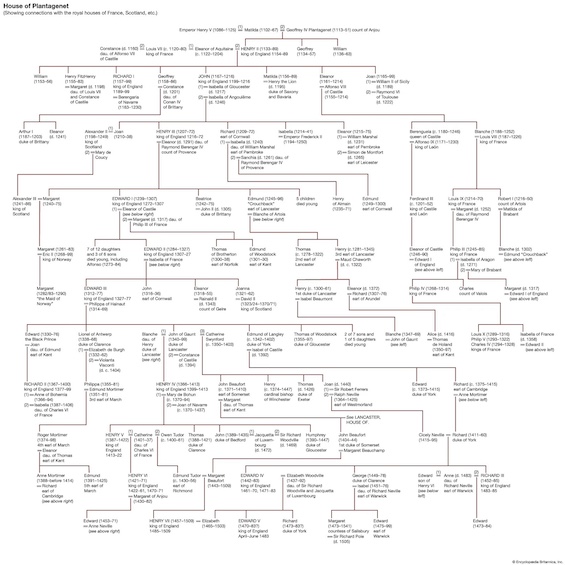

They ruled England (and Wales, Scotland, and Ireland from time to time) for more than three centuries. By my count, there were sixteen of them in all. They held sway, sometimes shakily, from 1154 to 1485. French in origin—their family’s roots lay in the County of Anjou—the Plantagenet kings reigned during the High and Late Middle Ages, when the English language evolved into Britain’s dominant tongue and the British parliamentary system began to take shape. But even the greatest of them—arguably, Henry II (1154-89), Edward III (1327-77), and Henry V (1413-22)—more closely resembled gangsters than today’s docile monarchs. And their dramatic stories come into high relief in The Plantagenets: The Warrior Kings and Queens Who Made England, British popular historian Dan Jones’ brilliant account of England’s longest-ruling dynasty.

Two centuries of unending drama

Although the Plantagenets reigned from the mid-twelfth century nearly to the end of the fifteenth, historians typically distinguish between the House of Plantagenet proper (1154-1399) and the Houses of Lancaster and York (1399-1485). Jones’s account covers the former period. During the latter, the cadet branches of the Plantagenet Dynasty contended for power in the Wars of the Roses, which would justify a book of its own. (Don’t be surprised if Jones produces one in the years ahead.) In any case, the eight Plantagenet Kings of the twelfth, thirteenth, and fourteen centuries provide quite enough drama to justify the nearly six hundred pages of The Plantagenets. It’s a tour-de-force of historical scholarship in a readable popular account.

The Plantagenets: The Warrior Kings and Queens Who Made England by Dan Jones (2012) 561 pages ★★★★☆

One damned king after another

The greatest strength of this book is also its greatest weakness. By limiting his account to a detailed (and colorful) story of the lives of eight men and their families, Jones opens himself up to the common complaint of schoolchildren who study British history: it’s just one damned king after another. And, yes, the succession of Henrys, Edwards, and Richards does become tedious at times. Tedious, that is, if a tale of recurring violence, treachery, and greed can be considered boring. Because the men of England’s longest-ruling dynasty apparently were, without exception, violent, treacherous, and greedy.

The signal events of the era when the Plantagenets ruled—the Magna Carta, the murder of Thomas Beckett, the Hundred Years’ War, the Black Death, and the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381—receive due mention, but they crowd into the background. For example, Jones devotes no more than a few paragraphs to the Black Death, which reduced England’s population by at least one-third (and some say one-half). In fairness, the Magna Carta and its future iterations do occupy Jones’s attention in the book. They crop up repeatedly. But The Plantagenets is not a history of Britain in the Middle Ages. Jones does a far better job of that in his superb survey, Powers and Thrones: A New History of the Middle Ages. This is the story of a dynasty, pure and simple.

What are kings (and dictators) for?

If there is any single reason why government exists, it’s surely the need for stability. Not the stability induced by terror, which is anything but reassuring, but that enabled by a set of easily understandable rules that permit us to live our lives in peace and attain whatever success might be within our ability. Yet the sad, violent history of the Plantagenets dramatically illustrates just how unstable government can be when a single person holds all the reins of political power.

The succession from one king to another was often disputed, leading to civil war. And from time to time one ruler or another would prove to be either incompetent or malevolent (or both), occasioning instability even before the end of his reign. All of which suggests just how bad an idea is today’s worldwide drift toward authoritarianism. Yet untold millions yearn for it, envisioning a strongman to make their lives easier. But consider: how much more stable has the world become under Vladimir Putin, Xi Jinping, Kim Jong Un, Jair Bolsonaro, Viktor Orbán—and Donald Trump?

About the author

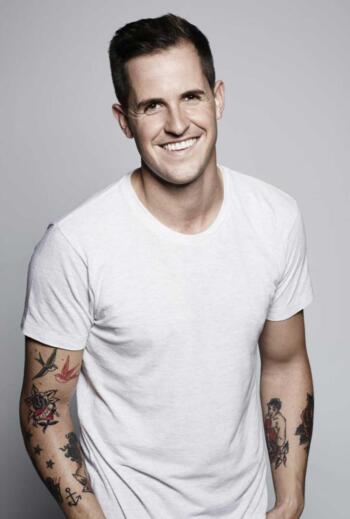

Dan Jones was born in Reading, UK, in 1981 and educated at Pembroke College, Cambridge. He has since become one of the most accomplished popular historians in Great Britain. He is the author of eleven works of history and a columnist at the London Evening Standard. Jones is also a TV presenter and journalist. He lives in Staines-upon-Thames with his wife, two daughters, and son.

For related reading

I’ve also reviewed another of the author’s books: Powers and Thrones: A New History of the Middle Ages (Change in the Middle Ages came thick and fast).

You’ll find books on related subjects at:

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.