When future historians look back at the most consequential events of the century just past, it seems likely they’ll place four or five episodes at the top of their lists. The Russian and Chinese Revolutions, of course. The thirty-year war that encompassed the two conflicts we now call the First and Second World Wars. And decolonization, beginning with the independence of India. But at the very top of that list is almost certain to be the decades-long upheaval that culminated on October 1, 1949, with the founding of the People’s Republic of China. And Helen Zia has done an extraordinary job of portraying the decade that preceded it through the lives of four remarkable young people who fled Shanghai in Last Boat Out of Shanghai.

Last Boat Out of Shanghai: The Epic Story of the Chinese Who Fled Mao’s Revolution by Helen Zia (2019) 493 pages ★★★★★

Four characters carry this eye-opening story

Zia uses the tools of biography to paint a wide-screen view of China’s troubled history from 1937, when Japan launched World War II by invading the country, to 1949 and beyond. Her principal subjects are two women and two men among the estimated one million Chinese who fled Shanghai as the Red Army neared the city.

Bing Woo

Bing Woo had been twice cast off as an unwanted girl child, first by her birth parents, then by an adoptive mother. In 1937 she was living with her third family, a “frightened girl of nine,” when Japan invaded Shanghai and other ports on China’s coast. And Bing was twenty when she stepped with her adoptive “Elder Sister,” Betty Woo, onto the General Gordon—the repurposed American warship put to work as the eponymous “last boat out of Shanghai”—en route to the United States. Three weeks after her departure, the People’s Liberation Army marched victorious into Shanghai.

Annabel Annuo Liu

Annuo (pronounced “ann-wah”) Liu was two in 1937. She was the daughter of a largely absentee father, an official in the Nationalist government, and a mother trained as a physician. Over the ensuing years, Annuo’s father was repeatedly promoted. Because his increasing visibility posed risks for the family, he forced them to leave the city and undertake a long and perilous journey to join him in the interior.

He repeated the practice in 1949, sending them from Hangzhou (near Shanghai) to Hong Kong, en route to Taiwan. There, he forebade Annuo’s mother to work. “He could not tolerate losing face by having a working wife.” At the same time, he imposed a long list of unreasonable restrictions on the thirteen- and fourteen-year-old girl. She was a star student desperate to enroll at Taiwan’s leading university to study English literature, but he stood in the way of that, too, forcing her to take up the law instead.

Benny Pan

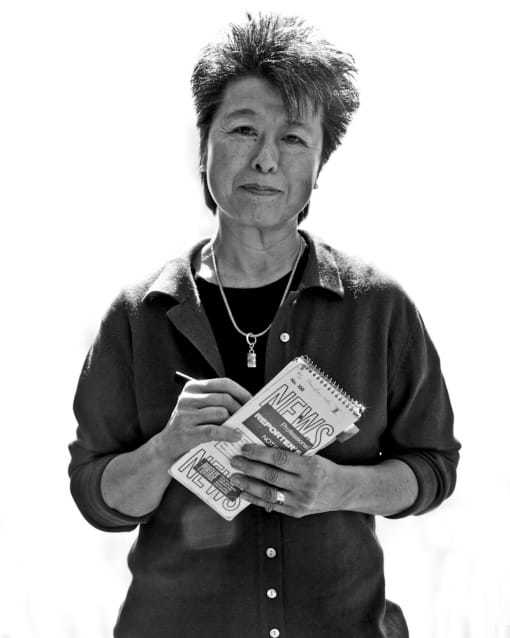

The image at left shows Benny Pan as a teenage bodybuilder attempting to please his powerful father. At nine years of age, Benny was “a privileged child of Shanghai,” living in the luxurious confines of the French Concession when war broke out in 1937. His father, Pan Zhijie, later known as C. C. Pan, was a well-to-do accountant with the British-run Shanghai Municipal Police. Following the invasion, he secured first one promotion, then another, eventually ending up as Police Commissioner for the region that encompassed the gangster-dominated Badlands.

Pan Zhijie swore an oath to the notorious Green Gang, which closely collaborated with Chiang Kai-shek and his Nationalist Party. After the invasion, Benny’s father—and the Green Gang—switched sides. They actively collaborated with the Japanese, presiding over the torture and execution of suspected Chinese Nationalist and Communist agents alike, gaining great wealth as a result. Late in 1948, Benny’s father was imprisoned by Nationalist troops on their return to the city. To escape the association with him, Benny fled Shanghai for the interior at age twenty.

Ho Chow

Ho Chow, thirteen in 1937, was “the playful second son” of a family of “landowning gentry for generations.” They lived in an enormous compound behind a moat in the farming town of Changshu in the fertile Yangtze River Delta. The boy was unusually bright, with “a gift in mathematics and science,” and fiercely pursued his studies, often against great odds during the war and the turmoil and uncertainty that followed it. He graduated first in his class from Shanghai’s Jiao Tong University, the “MIT of China.”

In 1947, Ho emigrated to Ann Arbor to study mechanical engineering at the University of Michigan, determined to acquire the tools he’d need to launch an automobile manufacturing company. After much difficulty with the INS, he managed to obtain work for an American company, where over the years he garnered “more than sixty industrial design patents.” And he did in fact found a small company of his own in New Jersey.

Eventually, all four—Bing, Annuo, Benny, and Ho—ended up in the United States and married. And they all later patronized the same Shanghainese restaurant in Manhattan, where they might well have encountered one another.

A time of terrible trouble

All the while she recounts the intimate and all too often excruciatingly painful stories of her four subjects’ lives, Zia surveys the disintegrating society in which they lived. To grasp the tumultuous reality of China in that era it’s no surprise that more than one million people fled Shanghai.

- Inexpressible cruelty and sadism practiced by the invading Japanese troops, their “scorched-earth approach of ‘Kill all, loot all, burn all'” displayed most dramatically in the Rape of Nanjing and in their use of “special bombs containing fleas infected with bubonic plague, cholera, anthrax, and other deadly germs.”

- The utter incompetence of Chiang’s Nationalist government, which seemed at times to exist merely to enrich him and the members of his family with billions siphoned from American aid and onerous taxes on the population.

- Chiang’s sociopathic disregard for the life of his countrymen, illustrated most profoundly when “as many as eight hundred thousand civilians drowned after the Nationalist army blew up dams holding back the Yellow River” to slow the Japanese advance.

- The collapse of the Chinese economy in runaway inflation, which impoverished hundreds of millions.

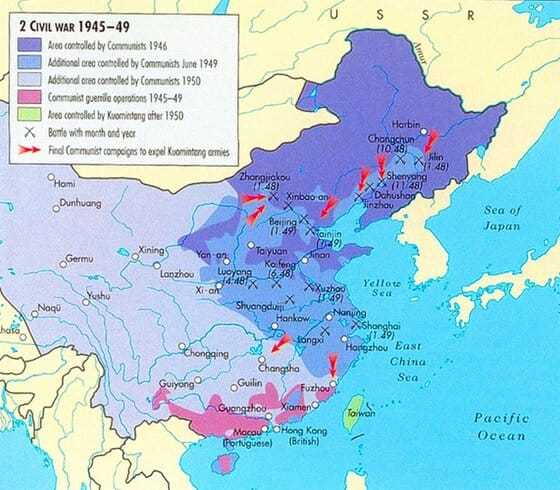

- Decades long-civil war between Nationalists and Communists, only sporadically interrupted by cooperation to resist the Japanese

A wrenching, eight-year war while revolution simmered

The eight-year war during which Japanese troops occupied large swaths of China dominates the stories unfolding in Last Boat Out of Shanghai. And Zia reveals facts about the war that are little mentioned in other accounts.

For example, “the Imperial Japanese Command had planned for Shanghai to fall in three days.” It took them three months. And “they had expected China to surrender in three months.” Those three months stretched to eight years. There’s an old joke that casts light on the challenge the Japanese faced. The two opposing armies have met in a big battle. Three hundred thousand Chinese die, but just 50,000 Japanese. Then another big battle takes place. There, 250,000 more Chinese die, and 75,000 Japanese. Pretty soon, the joke goes, “no more Japanese.” The seemingly inexhaustible demographic reserves of China, with its population then of half a billion, simply wore down the Japanese military machine. The Imperial Army won nearly every battle but emerged from the war thoroughly beaten.

After the Revolution

Although Zia devotes the lion’s share of her attention to the war years and the troubled time of revolution and civil war that followed, she pursues the stories of all four of her subjects after October 1, 1949 as well.

- For Benny Pan, who remained in mainland China for decades, the experience included the Great Leap Forward, the Cultural Revolution, and years of ill treatment at the hands of authorities because of his class background.

- Annuo Lu suffered through life as an impoverished refugee in Hong Kong until she was able at length to travel across the water to Taiwan. There, she and her family remained stranded for years, enduring the dislocations and harsh rule of the Kuomintang government as well as her tyrannical father.

- Both Bing Woo and Ho Chow fled Shanghai and made their way directly to the United States, where they learned first-hand how many roadblocks immigrants face in a xenophobic society.

About the author

Chinese-American journalist Helen Zia (born 1952) is considered a key figure in the Asian-American movement and is active in promoting LGBTQ rights. Last Boat Out of Shanghai is her third book. It was inspired by the experiences of the war and the revolution she heard from her mother, Bing Woo.

For further reading

Check out Shanghai 1937: Stalingrad on the Yangtze by Peter Harmsen (The 1937 Battle of Shanghai that started World War II).

This book is one of the best Books about World War II in the Pacific.

You might also be interested in:

- 20 insightful books about China reviewed on this site

- Great biographies I’ve reviewed: my 10 favorites

- 10 top nonfiction books about World War II (plus many runners-up)

- 20 top nonfiction books about history

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, plus a guide to this whole site, on the Home Page.