Estimated reading time: 7 minutes

China was not ready for war when the Japanese struck Shanghai on August 13, 1937. Despite six years of warning after the Empire of Japan occupied Manchuria in 1931, Chiang Kai-shek’s forces were woefully unprepared for the battle that started World War II in China.

- His army consisted of 176 divisions on paper, but only twenty full-strength (10,000-man) divisions answered directly to him. The others were either fielded by warlords, commanded by generals who ignored Chiang’s orders, or were led by Communists, with whom Chiang had negotiated a shaky truce.

- German military advisors had managed to train and equip some of Chiang’s loyal twenty divisions. But they lacked modern tanks, heavy artillery, a viable fleet on the rivers and coasts, and a modern air force. For example, “of the 600 aircraft officially forming the air force at the start of the hostilities, only 91 were actually ready to fight.” And some of those who did manage to get into the air in the ensuing battle may have bombed more Chinese civilians than Japanese soldiers.

- The Chinese military intelligence service was preoccupied with rooting out Communists and possessed few precious inroads into the city’s large Japanese community.

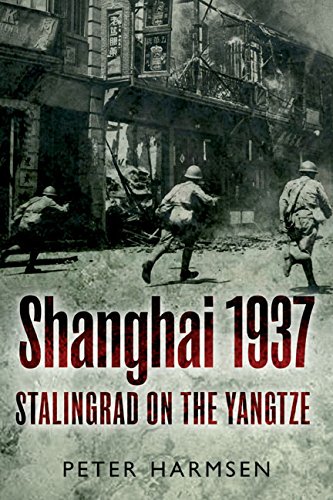

This grim picture comes to light in Shanghai 1937, Peter Harmsen’s deeply researched account of the long-neglected Battle of Shanghai (August 13 – November 26, 1937). It’s a story of “weeks of combat that would rival the battlefields of the Great War in their pointless waste of human life.”

An overconfident foe

To an outsider, a rapid Japanese victory in the 1937 Battle of Shanghai might have appeared inevitable. Emperor Hirohito and the militarists who commanded the Japanese Imperial government shared that opinion. After all, the country had been building its military into a world-class force for nearly seventy years since the Meiji Restoration of 1868. The Chinese were no match for the mechanized might of the Japanese Army on land and its superiority both in the air and on the water. Unsurprisingly, then, as Harmsen notes, “[i]n their habitual disdain for the Chinese, the Japanese leaders figured that this would be more than enough to deal with the nuisance across the sea.” They expected to take Shanghai within days. “Underestimating the foe was a mistake they were to repeat again and again in the coming weeks and months.”

Shanghai 1937: Stalingrad on the Yangtze by Peter Harmsen (2013) 390 pages ★★★★☆

A detailed, week-by-week account of the 1937 Battle of Shanghai

Shanghai 1937 casts light on the desperation of the Chinese resistance to the Japanese invasion and on the complex operations of the Chinese Army under Chiang Kai-shek. Harmsen introduces us to the senior generals who guided operations in and around Shanghai, both Chinese and Japanese as well as the German advisers who played such a prominent role on the Chinese side. (Japan and Germany had yet to sign the pact that formed the Axis.)

Harmsen describes the deployment of troops on both sides, allowing the reader to follow the confusing course of the battle by consulting maps included in the book. We learn how Japanese overconfidence forced its generals to request reinforcements from Tokyo at several crucial points in the battle. At times, Harmsen relates the experiences of some of the many European and American expatriates who lived in the city and witnessed the fighting. He draws from contemporaneous journalistic accounts as well. Some passages that illustrate the plight of individual soldiers and the deprivations of the city’s civilian population are poignant and revealing. The 1937 Battle of Shanghai was a human drama of epic proportions.

Overall, though, Peter Harmsen serves up more than I care to know about the Battle of Shanghai. Chinese with ties to the people or places involved or military history buffs may find the account more rewarding. However, the author has done a great service by writing this book. As he notes in the prologue, “Not a single monograph of this crucial encounter is listed among the hundreds of thousands of volumes dealing with World War II and its antecedents.”

Documented Japanese brutality

No account of the Japanese invasion of China is complete without acknowledging the inhuman brutality of the Japanese Army. Graphic, stomach-churning examples fill Shanghai 1937. Here, for example, is what one Japanese soldier described after the war: “‘We’d take all the men behind the houses and kill them with bayonets and knives . . . Then we’d lock up the women and children in a single house and rape them at night. I didn’t do that myself, but I think the other soldiers did quite a bit of raping. Then, before we left the next morning, we’d kill all the women and children, and to top it off, we’d set fire to the houses, so that even if anyone came back, they wouldn’t have a place to live.'”

The book also reveals that “Japanese aircraft deliberately machine-gunned and bombed anything that bore the Red Cross.” However, as Harmsen emphasizes, neither side took prisoners. Both summarily executed captured soldiers in short order.

The lasting impact of the Battle of Shanghai

After three months of brutal, back-and-forth combat, “the total number of Japanese military casualties in the battle was 9,115 dead and 31,257 injured. But “the Japanese estimated that China had suffered 250,000 military casualties fighting for the city. . . [T]he Chinese put the number at 187,200. Some even estimated that it was as high as 300,000. No matter the exact figure, the result of the battle was carnage of catastrophic dimensions, which hit Chiang Kai-shek’s best German-trained divisions with disproportionate severity. China took a beating that it would not recover from fully until 1944, after massive American aid.”

About the author

Google Books notes that “Peter Harmsen, a foreign correspondent in East Asia for two decades, has worked for Bloomberg, the Economist Intelligence Unit, and the Financial Times. A fluent speaker of Mandarin Chinese, Harmsen is also the former bureau chief in Taiwan for French news agency AFP. His book Shanghai 1937: Stalingrad on the Yangtze inspired a US Public Television documentary by three-time Emmy Award winner Bill Einreinhofer, which started airing in the fall of 2018, reaching 80 percent of the American television audience. Harmsen’s work has been translated into Chinese, Danish, and Romanian.” In addition to Shanghai 1937, he has written four other books about World War II in East Asia.

For related reading

This book is one of the best Books about World War II in the Pacific.

I’ve also reviewed Storm Clouds Over the Pacific, 1931-1941 (War in the Far East #1 of 3) by Peter Harmsen (The first decade of World War II in the Pacific).

Check out Last Boat Out of Shanghai: The Epic Story of the Chinese Who Fled Mao’s Revolution by Helen Zia (A gripping account of four young Chinese who fled Shanghai).

You might also enjoy:

- 10 top nonfiction books about World War II

- 30 insightful books about China

- The 10 best novels about World War II

- 7 common misconceptions about World War II

- The 10 most consequential events of World War II

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.