In his Pulitzer Prize-winning 1997 book, Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies, Jared Diamond delved into biogeography to explain how the West developed faster and soon became much richer than the rest of the world. The book was an early effort to explore the gap between the Global North and Global South.

Estimated reading time: 9 minutes

Why is the Global North so much richer?

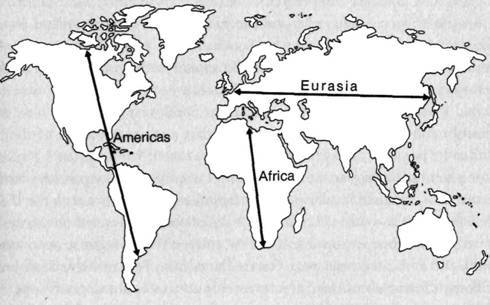

The fundamental reason, Diamond asserted, lay in accidents of geography: the Eurasian landmass straddles the globe laterally from East to West, imposing relatively uniform climatic conditions and creating habitats congenial for large animal species such as the cow, the pig, and the sheep that could be readily harnessed for human use. By contrast, the lands of Africa and the Americas are arrayed from North to South and host very few native varieties of such useful large animals. Condensed into one paragraph, this argument raises far more questions than it answers. But laid out in its full glory in Diamond’s engrossing book, the thesis is compelling despite the controversy that continues to surround it.

A Farewell to Alms: A Brief Economic History of the World, by Gregory Clark (2008) 431 pages ★★★★★

Jared Diamond is one of a handful of Big Picture thinkers who have attempted with mixed success to make sense of the ebb and flow of human history. Adam Smith was another. So was Karl Marx. Each, in his own way and working within his own discipline, revealed some startling insight about how we came to be the way we are.

Exploring the gap between the Global North and Global South

Ten years after Diamond’s blockbuster came Gregory Clark’s A Farewell to Alms, yet another effort to answer that same profound question addressed in Guns, Germs, and Steel. Why, he asks, are some parts of the world so much richer than others? What explains the yawning gap between the Global North and Global South? Dismissing Diamond, Smith, and Marx alike and finding inspiration instead in Thomas Malthus’ An Essay on Population, Clark locates the answer in his own discipline of economic history. (Why is that not a surprise?)

In a volume riddled with charts, graphs, and “simple” equations only an economist could love, Clark reduces the bigger question to one that’s far more focused: why did the Industrial Revolution occur in Europe, and specifically England, and not somewhere else in the world? Clark’s answer, it turns out, is that beginning in the late Middle Ages rich people in England had more than twice the number of children who survived past the age of five as did the poorest people, so that over the centuries from 1200 to 1800 “bourgeois values,” the attitudes and behaviors that had made people rich, gradually took hold throughout society.

400 pages of charts and graphs to convince you

How did this happen? Because of primogeniture in Europe. There, only first sons inherited the wealth, driving later sons into downward mobile circumstances and thus displacing the poor. “China and Japan did not move as rapidly along the path as England simply because the members of their upper social strata were only modestly more fecund than the mass of the population. Thus there was not the same cascade of children from the educated classes down the social scale.” If you doubt this facile line of argument, Gregory Clark has 400 pages of charts and graphs to convince you.

Before 1800, the “Malthusian Trap”

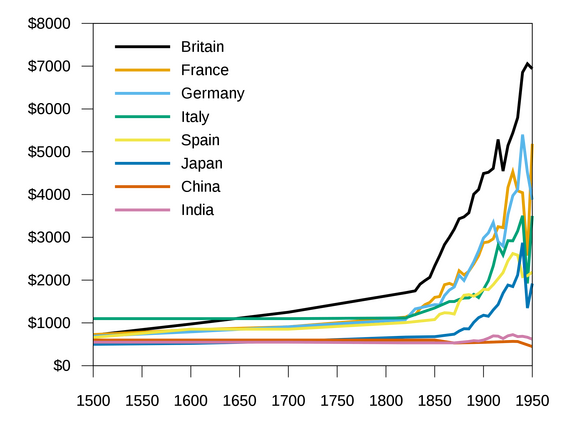

A Farewell to Alms divides human history into two very broad eras: from the beginning of known history approximately 10,000 years ago, until about 1800; and from 1800 until the present—and beyond. In fact, until 1800, the gap between the Global North and Global South was the opposite of today’s: the world’s richest nations by far were India and China.

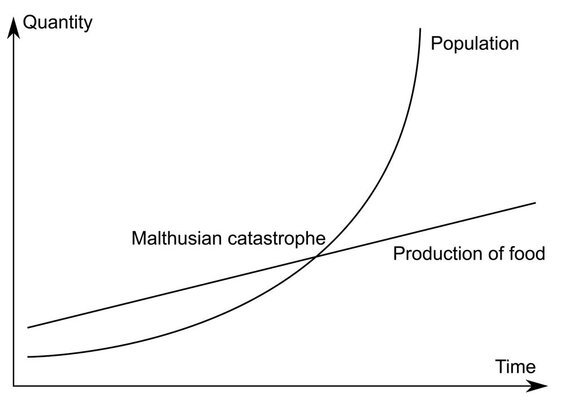

Before the Industrial Revolution, Clark asserts, humankind was enmeshed in the Malthusian Trap, a feedback loop in which population grew to consume the food available but died off as it grew too numerous to survive. For millennia, in Clark’s view, the population thus grew at a painfully slow pace from year to year, expanding only to meet the equally slow expansion of agriculture into new regions of arable land, with no sustained gain in income per person.

“The average person in the world of 1800,” Clark writes, “was no better off than the average person of 100,000 BC. Indeed in 1800 the bulk of the world’s population was poorer than their remote ancestors.” While this assertion remains controversial, there is a substantial amount of evidence to support it. The hunter-gatherers of the Paleolithic Era subsisted on a far more balanced diet and lived in small communities much less susceptible to infectious disease. Those who lived in daily proximity to farm animals or in crowded cities were vulnerable to periodic epidemics. They were also weakened by their reliance on the cereal grains that dominated their diet.

1800: “The Great Divergence”

Then, around 1800, what has come to be called the Great Divergence took place. Whether the inflection point was 1760 or 1820, as other scholars have suggested, the event that rescued the human race from the Malthusian Trap was the Industrial Revolution. During the century from 1760 to 1860, England’s population tripled—but instead of collapsing in Malthusian fashion, the English people grew richer. So it went throughout much of Europe as well, and thus began the Great Divergence between West and East. For nearly the next 200 years, income per person in those countries that had experienced the Industrial Revolution continued to climb. Meanwhile, population in much of the rest of the world stagnated (and, in Africa, declined). Clark concludes, “There walk the earth now both the richest people who ever lived and the poorest.”

Are we free from the Malthusian Trap?

There’s no denying that income inequality has risen to the greatest extent in human history. Although it’s true that tiny numbers of high-ranking aristocrats in the ancient and pre-modern world may well have lived in luxury while their subjects barely survived, the contrast today between the top five or ten percent of the human race and the rest of us is far more consequential. But Clark’s insistence that the Industrial Revolution brought an end to the Malthusian Trap may be premature.

As global population mounts steadily toward ten billion, we have long since exceeded the carrying capacity of Planet Earth. The consequences remain to be seen. In fact, by the middle of the twentieth century, famine stalked millions in Southern and Eastern Asia and threatened other populous regions. Only the Green Revolution saved the day for the next several decades. But now, once again, with the climate crisis accelerating, massive problems are a certainty. Millions dying of thirst or heatstroke. Brutal wars over ever-scarcer resources. And quite possibly a killer pandemic even more deadly than the 1918 Spanish Flu that killed as much as five percent of the world’s population. Today’s COVID-19 pandemic suggests it’s possible. Malthus may yet have the last word.

The single biggest reason: innovation

Why did the West outpace the rest to such a glaring extent? Clark reasons his way through one popular explanation after another, dismissing them all, and ends up with a single-factor answer: innovation. It was the constant flow of new ideas that enabled the people of the West to increase productivity year after year at a steady rate, enriching their societies and widening the gap between rich nations and poor to the greatest extent ever seen in world history. That ratio now approaches 100:1.

But does innovation alone explain how this came about? Surely, the West has never had a monopoly on innovation. Much of what made the Industrial Revolution possible was rooted in advances in China (paper-making, printing, the compass, and gunpowder) and India (algebra and the decimal system, including the concept of zero). It’s true, of course, that for the last two centuries innovation in technology was primarily confined to the West. But that is by no means any longer the case. Much of the most advanced technological research and development is now underway in China and India.

Challenging, thought-provoking . . . and tedious

A Farewell to Alms is challenging, thought-provoking, perhaps even important. It’s also frustrating and an exceedingly tedious read. Perhaps someday a writer with an engaging style and much less affinity for charts, graphs, and formulas will render Gregory Clark’s thesis into a more readable form.

About the author

Gregory Clark was born in Scotland in 1957 and educated at Harvard and Cambridge universities. He now teaches economic history at the University of California, Davis. A Farewell to Arms was the first of the two books he h as written to date.

For related reading

This is one of the books I’ve included in my posts, Good books about economic inequality and Gaining a global perspective on the world around us.

You might also be interested in Why the West Rules—for Now: The Patterns of History, and What They Reveal About the Future by Ian Morris (Is history too important to leave to historians?).

See also:

- The top 10 books on the economics of poverty

- 20 top books about Africa, including both fiction and nonfiction

- 20 top nonfiction books about history

- New perspectives on world history

If you enjoy reading history in fictional form, check out 20 most enlightening historical novels.

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.