In March 1985, a little known Communist Party apparatchik named Mikhail Gorbachev ascended to the pinnacle of leadership in the Soviet Union. He was the country’s fourth supreme leader in four years, and he took charge as the USSR was in steep decline following seven decades of Communist rule. As Gorbachev struggled to combat corruption, loosen the bonds of central planning, and open up Soviet society to new ideas, life for the overwhelming majority of the country’s 288 million citizens changed little. The deprivation they experienced, and the pain it caused them, is everywhere evident in Stuart Kaminsky’s able police procedural set in Gorbachev’s Russia, A Fine Red Rain.

Estimated reading time: 5 minutes

A police procedural that breaks the mold

The novel is the fourth of Kaminsky’s sixteen books featuring Inspector Porfiry Rostnikov. It’s a police procedural that sets new rules. In most such novels, investigators work as a team to solve crimes. In A Fine Red Rain, Inspector Rostnikov has been isolated from his colleagues in the Moscow procurator‘s office and transferred to the lowly MVD. There, he is blocked from investigating any major case. His two closest collaborators, Emil Karpo and Sasha Tkach, remain behind. And each of the three individually tackles a different case.

Rostnikov, Karpo, and Tkach come together in secret once or twice in the evening to compare notes. Though they don’t actively collaborate, Rostnikov plays a supporting role at the climax of each of their cases. But, unlike the stories in novels by such authors as Michael Connelly and Ian Rankin, the three investigations are unrelated. The diversity offers Kaminsky an opportunity to convey a more complete picture of life in Gorbachev’s Russia.

A Fine Red Rain (Porfiry Rostnikov #4 of 16) by Stuart M. Kaminsky (1987) 228 pages ★★★★☆

Three unrelated criminal cases

Each of the three leading cases portrayed in A Fine Red Rain casts light on an aspect of Soviet society that is little known to the reading public.

Rostnikov

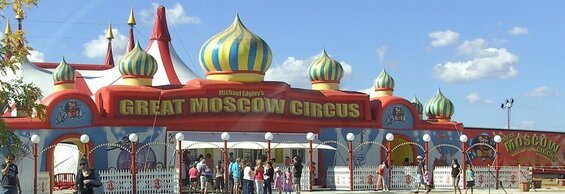

Rostnikov witnesses the public suicide of a drunken circus acrobat and learns that the man’s partner has died at the circus in a highly suspicious “accident.” We learn about the privileged lives led by performers in the New Moscow Circus as well as other athletes and artists favored by the state. What stands out is that their privileges pale beside those of the members of the Politburo and other Communist Party leaders.

Karpo

Inspector Karpo has detected a pattern in the murders over many years of Moscow prostitutes. His patient investigation leads him to conclude that the killer is a police officer. We know, from other accounts, that for decades the regime insisted there was no such thing as a serial killer in the Soviet Union. The deranged man responsible in this case reflects how the system spawns such crime. And Karpo’s obsessive devotion to the state dramatizes how, even in its final years, Communism still attracted fanatics in Gorbachev’s Russia.

Tkach

Young Sasha Tkach is assigned by the Deputy State Procurator to go undercover as a student to investigate black marketeers who sell bootleg videos of American films and video players. When he reports back on his success, the Procurator takes control of the operation himself. He forces himself on the crooks as a partner and walks away with a fortune in their merchandise. In the Soviet Union, black marketeers were “economic criminals” subject to the death penalty, so there is no doubt why the crooks would agree to the deal.

Not a traditional mystery

A Fine Red Rain isn’t a mystery in the traditional sense, since we know early on who is responsible for each of these crimes. The mystery lies in the clever ways Inspector Rostnikov and his colleagues go about resolving each case. And then the more important point emerges when we see how the criminals go free in the corrupt Soviet system. Although police were much more numerous in Gorbachev’s Russia than in the United States, and crime was less prevalent as a result, it is of course a myth that Communism eliminated crime.

For related reading

This is one of a superb series of Police procedurals spanning modern Russian history.

I’ve reviewed all three previous novels in the Porfiry Rostnikov series as well as the fifth, which won the Edgar Award for Best Novel::

- Death of a Dissident (A grim murder mystery set in the USSR)

- Black Knight in Red Square (The collapse of the USSR is underway in this detective novel)

- Red Chameleon (A Russian police procedural set in the Soviet Union)

- A Cold Red Sunrise (A historical mystery about a murder above the Arctic Circle)

You might also enjoy my posts:

- Two dozen outstanding detective series from around the world

- Top 10 historical mysteries and thrillers reviewed here

- Top 10 mystery and thriller series

- 20 excellent standalone mysteries and thrillers

- 5 top novels about private detectives

For an abundance of great mystery stories, go to Top 20 suspenseful detective novels

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.