Estimated reading time: 7 minutes

Chief Inspector Porfiry Petrovich Rostnikov is out of favor. He had tried to blackmail a senior KGB official in hopes of obtaining exit visas for himself and his Jewish wife. Given widespread antisemitism, they hoped to emigrate to the United States. At the time, his boss, Assistant Procurator Anna Timofeyeva, had valued his work and managed to shield him from the worst consequences. But she suffered a heart attack and was forced to retire. The new Deputy Procurator General of Moscow, Khabolov, has followed orders and assigned the serious cases to Rostnikov’s subordinates instead of him. And now first one major case then another opens up. Rostnikov is forbidden to work them. But the “unimportant” murder of an old Jewish man who was shot in his bathtub might lead to something big. Thus begins Red Chamelion, the third Russian police procedural in Stuart Kaminsky’s captivating series featuring Inspector Rostnikov.

Turmoil in the Soviet Union

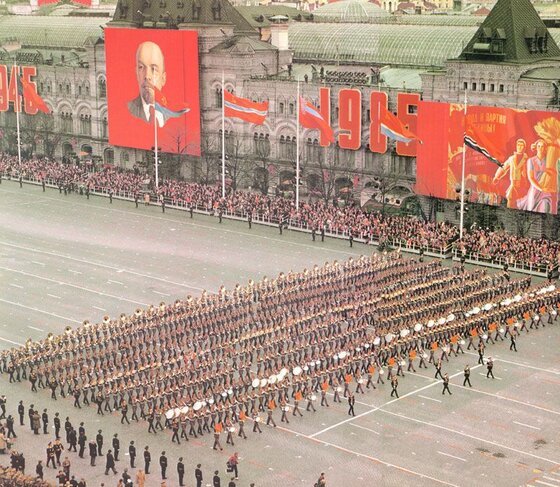

So goes the career of Inspector Rostnikov, “the best cop to come out of the Soviet Union” in the words of the San Francisco Examiner. It’s 1985, and the USSR is in turmoil. Chairman Leonid Brezhnev had died three years earlier, and his successor, KGB Chairman Yuri Andropov, had lasted little more than a year. Now Andropov’s successor, Konstantin Chernenko, is dead too. And the man who will take his place, Mikhail Gorbachev, is little-known and unpredictable. In the midst of the uncertainty, “a sniper has been shooting at people from the rooftops in Central Moscow”—and “a well-organized team of automobile thieves” has been snatching the luxurious Chaikas and Zil limousines belonging to the only men who could possibly afford them: senior Party apparatchiks. It’s a terrible time for Inspector Rostnikov to be sidelined.

Red Chameleon (Inspector Porfiry Rostnikov #3 of 16) by Stuart M. Kaminsky (1985) 303 pages ★★★★☆

Three cases collide in this Russian police procedural

Suddenly, Assistant Procurator Khabolov calls Rostnikov into his office in a panic. Now his beloved white Chaika automobile has been stolen. This, of course, elevates the case to the highest priority. And while the Chief Inspector is working to recover the car, he’s free to investigate the sniper as well. The shooter, who may be either a man or a woman, has murdered a policeman, which is unacceptable. But Rostnikov is to keep the priorities straight: the Chaika comes first. And, as far as Khabolov is concerned, he might as well forget about that murdered old Jewish man. Somehow, though, we know that Rostnikov will find a way to resolve all three cases. And how he does so—simultaneously—with the able assistance of his team, is wonderful to behold.

Life in the Soviet Union

Nearly seven decades after the Russian Revolution (1917-21), the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics was showing its age. The promise of an equitable society had long since been abandoned in all but name. For everyone but a tiny elite, the USSR’s 274 million people lived day by day with a harsh reality wrought by misguided priorities. Long lines for food that never met the demand. Dilapidated housing nobody ever maintained. Factories that met arbitrary quotas by churning out torrents of goods nobody would ever buy. Empty shelves on stores offering household appliances that never materialized. Antiquated hospitals and incompetent doctors. And everywhere, police, shopkeepers, and petty officials demanding bribes to supplement their meager wages. As the old joke went, “They pretend to pay us, and we pretend to work.”

What it was like then

In Red Chameleon, Rostnikov rejoices when he finds “a bakery where the line to find out the price was reasonably short. He got the price then went to the line to pay the cashier. Ten minutes later he had gone through the third line, the one to pick up the bread and was on his way home.”

Later, Emil Karpo, one of Rostnikov’s assistants is injured on the job and winds up in a hospital. Knowing how the system works, the Inspector has called in a family friend, a foreign-trained doctor, to help Karpo. The doctor asks a few questions, looks him over carefully, and then advises, “‘You should get out of here as fast as you can. Tell them you feel fine before they operate on you and maim you for life, or worse, infect you in an unsterile environment. They are controlling you with drugs. Who knows what drugs.'”

If you’re skeptical of anything in this portrayal, I can assure you it’s all accurate. I witnessed all that and more on two visits to the Soviet Union, in 1965 and 1989.

The author’s inspiration

In the Inspector Rostnikov novels, Kaminsky makes abundantly clear that his model and inspiration are the 87th Precinct police procedurals of Ed McBain (1926-2005). The Inspector is addicted to these books, which he has bought “on the black market . . . and kept hidden in his apartment behind the Russian classics and the collected speeches of Lenin.” Rostnikov marvels at “Ed McBain’s world of police who caught criminals and knew nothing of politics, of police who were supported by their system.” But the Inspector didn’t read McBain alone. “It had become a ritual need of her husband’s to read at least a few pages of Ed McBain or Lawrence Block, Bill Pronzini, or Joseph Wambaugh.” Small wonder, then, that Kaminsky chose to craft his novels about Inspector Rostnikov as Russian police procedurals.

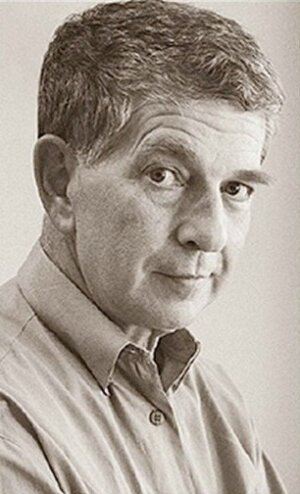

About the author

The late Stuart M. Kaminsky (1934-2009) wrote four series of mystery novels in a career spanning three decades (1977 to 2009). His output include more than sixty novels as well as story collections and nonfiction works. One of the sixteen books in the Inspector Rostnikov series won him the Edgar Award in 1989, and he received the Grand Master Award from the Mystery Writers of America in 2006. Kaminsky had served as president of that organization in 1998.

For related reading

This is one of a superb series of Police procedurals spanning modern Russian history.

For reviews of the first two books in this series, see:

- Death of a Dissident by Stuart M. Kaminsky (A grim murder mystery set in the USSR)

- Black Knight in Red Square (The collapse of the USSR is underway in this detective novel)

For views on recent Russian history and current affairs, see Good books about Vladimir Putin, modern Russia and the Russian oligarchy.

You might also enjoy my posts:

- 26 mysteries to keep you reading at night

- Top 10 mystery and thriller series

- 20 excellent standalone mysteries and thrillers

- 30 outstanding detective series from around the world

- Top 20 suspenseful detective novels

- Top 10 historical mysteries and thrillers

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.