The Partition of India in 1947 surely ranks among the greatest geopolitical disasters of the 20th century. In the long run, given the ongoing threat of nuclear war between India and Pakistan, Partition may yet prove to be the most consequential. And in Midnight’s Furies, a history of the Indian Partition, foreign affairs analyst Nisid Hajari brings a critical eye to the blood-soaked process that killed an estimated one million people, uprooted fourteen million refugees, and carved the subcontinent into the independent nations of India, Pakistan, and, later, Bangladesh. And what emerges most clearly from his account is that Partition might never have happened at all.

One man’s role stands out

That Pakistan (and, by extension, Bangladesh) exists today as an independent state is largely down to one man: Mohammad Ali Jinnah (1876-1948). The revered founder of Pakistan—the “Quaid-i-Azam,” or Great Leader—singlehandedly forced the question of an independent Muslim nation to the top of the agenda in the protracted, three-sided negotiations among the British Raj, the Indian National Congress, and the Muslim League.

In Midnight’s Furies, Hajari paints evocative, three-dimensional portraits of all the principal figures involved in Partition. Jinnah and Jawaharlal Nehru (1889-1964), of course. British Viceroys Archibald Wavell and “Dickie” Mountbatten. As well as the principal deputies for Jinnah and Nehru, Liaquat Ali Khan and “Sardar” (“chief”) Vallabhbhai Patel. None of these six men emerge from Hajari’s account free of blame for the catastrophe that was Partition. Even Mohandas Gandhi, of all people, fanned the flames of conflict at times.

Midnight’s Furies: The Deadly Legacy of India’s Partition by Nisid Hajari (2015) 312 pages ★★★★★

Partition in a nutshell

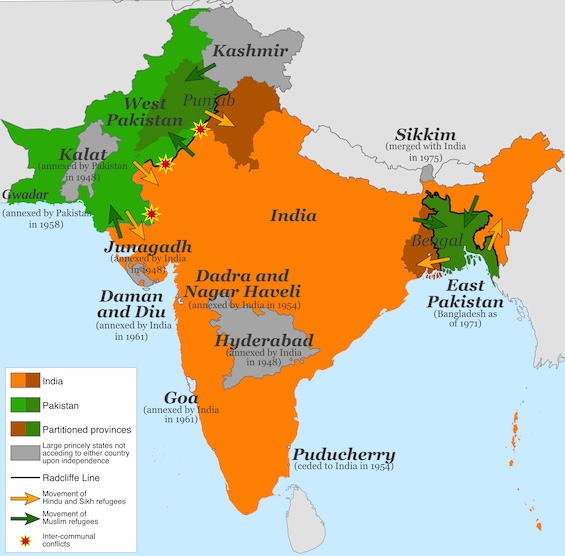

Pakistan took shape on the fringes of the subcontinent. Muslims formed a majority only in the western half of the province of Punjab and the eastern half of populous Bengal. Although the new state absorbed other territories as well, Pakistan consisted largely of those two regions. According to the 1951 census, Pakistan shortly after gaining its independence had a population of 75.7 million, with 33.7 million in the west and 42 million in the east. However, during Partition millions of Hindus and Sikhs had fled eastward out of West Pakistan and millions of Muslims fled west from their homes farther east.

A similar process unfolded in the east. But the fighting, and the death toll, was by far the greatest in the west, where bands of Sikhs, many with military training, formed into death squads to join extremist Hindus on the hunt for Muslim prey. The body count grew so rapidly that “vultures feasted so extravagantly that they could no longer fly.” And “the killings stopped when there was no one left to kill.”

What if it hadn’t taken place?

What if Jinnah had chosen not to press so single-mindedly for the creation of Pakistan, or been successfully rebuffed in his demands? Today, the three nations carved out of the subcontinent have a total population of nearly 1.8 billion, substantially larger than China’s. Nearly one-third would be Muslim, with roughly comparable numbers in each of today’s three major South Asian nations. Unquestionably, intercommunal violence would be a fact of life in a unified India, as it erupts today from time to time in Hindu-dominated India. But is it likely that a million people would have died—even after 75 years since India and Pakistan gained independence? I have my doubts.

I doubt, too, that Afghanistan would have descended into chaos under the Taliban without the driving force of Pakistani intrigues. And I suspect that Prime Minister Narendra Modi could not allow right-wing Hindu nationalists to have so free a hand, as they have today—assuming Modi could even have been elected in a nation much better balanced between Hindus and Muslims.

Sidestepping the assignment of blame

Hajari states that he didn’t set out to assign blame for the catastrophe that Partition became. In fact, he is painstakingly even-handed. “There is little question that Jinnah was the most polarizing figure in the Partition drama,” he writes. “He was criminally negligent about thinking through the consequences of the demand for Pakistan. . . Yet from the moment in 1937 when the Congress Party rejected any partnership with the Muslim League, Nehru . . . contributed nearly as much as Jinnah to the poisoning of the political atmosphere on the subcontinent.” And certainly that’s true, as Hajari’s detailed chronology makes perfectly clear. Yet the demand for Partition would not have become impossible to deny had Jinnah not inflexibly and heedlessly continued to raise it above all other issues over nearly a decade in the struggle for Indian independence.

Deconstructing the title

Midnight’s Furies: the title neatly encapsulates the reality Hajari recounts in 300 pages. India and Pakistan gained their freedom at midnight on August 15, 1947. But their liberation from Britain had already set off a “fury in the medieval sense,” as the author notes. The OED makes clear that the word migrated from the French to Middle English and connotes “frenzied rage . . . especially in battle.”

About the author

Nisid Hajari was born in Bombay and raised in Seattle, Washington. He is a writer, editor for Bloomberg News, and foreign affairs analyst who specializes in Asian affairs. Prior to Bloomberg News, he worked at Newsweek, including four years as a deputy to Fareed Zakaria. He holds a bachelor’s degree from Princeton and a Master’s from Columbia.

For more reading

This book is among The best nonfiction of 2022.

You might be interested in Good books about India, past and present. If you read fiction, you might enjoy Midnight at Malabar House by Vaseem Khan (A compelling murder mystery set in India after Partition), which includes an insightful view of the events of 1947.

For a broader view of history, see 20 top nonfiction books about history.

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, plus a guide to this whole site, on the Home Page.