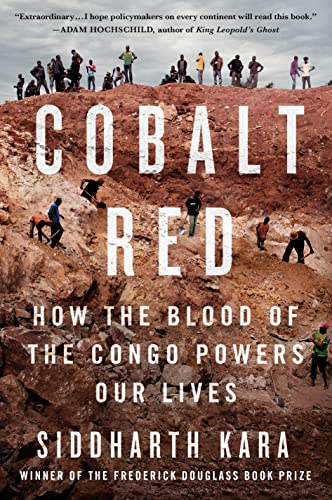

You may have come across reports about the violence surrounding the mining of the rare mineral coltan in Central Africa. It’s a source of the element tantalum, which is essential in the manufacture of cell phones and laptops. And about eighty percent of the world’s supply comes from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). But it’s hardly the only strategic resource found in large concentrations there. That’s the case, too, with the rare metallic element cobalt, which is easily confused with coltan. The American author Siddhartha Kara reveals the modern-day slavery involved in cobalt mining in the DRC in his chilling report, Cobalt Red: How the Blood of the Congo Powers Our Lives.

Estimated reading time: 7 minutes

Modern-day slavery, child labor, and the rape of the Earth

Cobalt is primarily used in lithium-ion batteries—for cell phone and electric vehicle batteries—as well as in the manufacture of high-strength alloys. And half of the world’s reserves of cobalt lie in the DRC, where it is usually mined as a byproduct of copper and nickel. There, enormous commercial mining companies, most of them Chinese, tear up the Earth at large-scale facilities. Seventy percent of the world’s cobalt is mined in the DRC. And 80 percent of that DRC output then heads to China for processing. There it makes its way into our iPhones and Android devices.

But cobalt doesn’t come solely from industrial mines. A “2020 report by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development estimated that between 18% and 30% of the cobalt produced by the Democratic Republic of the Congo is mined through artisanal mining.” That awkward phrase—”artisanal mining”—is a term of art in the industry. It’s a sly and misleading reference to the desperate local people who scrape the surface of the Earth or burrow into tunnels to gather cobalt ore in sacks. And most of them are children who rarely earn more than a pittance for work that will end their lives prematurely.

Cobalt Red: How the Blood of the Congo Powers Our Lives by Siddhartha Kara (2023) 288 pages ★★★★★

Much of the cobalt in our cell phones comes from child labor

The author’s investigation reveals that “the artisanal contribution of total cobalt production in the Congo could easily exceed even the highest estimates of 30 percent.” Why? Because “artisanal mining techniques can yield up to ten or fifteen times a higher grade of cobalt per ton than industrial mining can. This is the primary reason that many industrial copper-cobalt mines in the DRC informally allow artisanal mining to take place on their concessions, and it is also why they tend to supplement industrial production by purchasing high-grade artisanal ore from” the middle-men who buy it from exploited young miners.

How big is the problem?

“As of 2022,” Kara writes, “there is no such thing as a clean supply chain of cobalt from the Congo. All cobalt sourced from the DRC is tainted by various degrees of abuse, including slavery, child labor, forced labor, debt bondage, human trafficking, hazardous and toxic working conditions, pathetic wages, injury and death, and incalculable environmental harm.” The large companies who operate the biggest mines insist that none of this applies to them. This may be the case at scattered locations, where enormous machinery does most of the work. But even there the ore they mine is mixed with that from sites where children in rags work with their hands on the surface. And many, if not most, of the biggest companies encourage children to work over their land after the machines have moved on.

Who is to blame?

As noted above, 80 percent of the cobalt mined from the DRC goes to the several Chinese companies that dominate the industry there. A huge Swiss-based company is also prominent. The United States once was active in the country but that ended in 2016. Yet huge American companies such as Tesla, Apple, and Google are at the top of the author’s list of culprits for the crimes committed in mining cobalt. “The leviathans atop the cobalt supply chain do not want us to see” how the cobalt they use is really mined. To cover their tracks, they are prime movers in two global coalitions, the Responsible Minerals Initiative (RMI) and the Global Battery Alliance (GBA), which promote the responsible sourcing of minerals and safe working conditions in the industry. And claim everything’s mostly just fine as it is.

Yet, as Kara reports, “in all my time in the Congo, I never saw or heard of any activities linked to either of these coalitions, let alone anything that resembled corporate commitments to international human rights standards, third-party audits, or zero-tolerance policies on forced and child labor.” As he concludes, “our daily lives are powered by a human and environmental catastrophe in the Congo.” So, as Pogo says, we have met the enemy, and he is us.

The blame rests in the Congo, too

But there is still more blame to go around. None of the crimes committed in the mining of cobalt would be possible had it not been for the unbridled greed and ruthlessness of a succession of Congolese leaders. But even the notorious kleptocrats Mobutu Sese Seko, Joseph Kabila, and their ilk aren’t solely responsible. “So long as the political elite were content to continue the tradition of government-as-theft established by their colonial antecedents,” Kara asserts, “the people of the Congo would continue to suffer.”

A century ago novelist Joseph Conrad characterized Belgian King Leopold’s regime in the Congo as “the vilest scramble for loot that ever disfigured the history of human conscience.” Cobalt mining there today is not much different.

About the author

“Siddhartha Kara is an author, researcher, screenwriter, and activist on modern slavery,” according to his website at Harvard University. “He is an adjunct lecturer at the Harvard Kennedy School of Government, and a Visiting Scientist at the Harvard School of Public Health. Kara has authored three books on modern slavery: Sex Trafficking: Inside the Business of Modern Slavery (2009); Bonded Labor: Tackling the System of Slavery in South Asia (2012); and Modern Slavery: A Global Perspective (2017).” This new book on modern-day slavery in the DRC is his latest contribution to the field.

“Across twenty years of almost entirely self-funded research, Kara has traveled to more than fifty countries to document the cases of several thousand slaves of all kinds. He has mapped global human trafficking networks, explored the perilous underground of trafficked sex slaves, and traced global supply chains of numerous commodities tainted by slavery and child labor. Kara advises several UN agencies and numerous governments on anti-slavery policy and law. He has also appeared extensively in the media as an expert on modern slavery.

“Previously, Kara was an investment banker at Merrill Lynch, then ran his own finance and M&A consulting firm. He holds a Law degree from England, MBA from Columbia University, and BA from Duke University.”

For related reading

This is one of The 21 best books of 2023.

For perspective on the history of the Congo, I strongly recommend Adam Hochschild’s superb, prize-winning account of Belgian colonization there: King Leopold’s Ghost. I read the book shortly after its publication in 1998, more than a decade before I launched this blog, so you won’t find a review here.

You’ll see reviews of other great books about intersecting events and issues at 20 top books about Africa.

You might also care to check out:

- 20 top nonfiction books about history

- My 10 favorite books about business history

- Gaining a global perspective on the world around us

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.