Estimated reading time: 9 minutes

Most accounts of Allied spies in World War II highlight their heroic exploits. Stealing top-secret documents. Operating clandestine radios. Leading scores or hundreds of Resistance fighters in battle. Or blowing up Nazi troop trains. Aline Griffith did none of these things. But the fascinating story Larry Loftis tells in The Princess Spy reminds us that espionage then involved a great deal more than fighting on the front lines. His tale of a middle-class American woman who became an OSS spy and married into Spanish nobility offers its own rewards for readers eager to understand World War II in depth.

Four neutral countries in Europe were hotbeds of espionage during the war. Axis and Allied spies virtually tripped over one another in the major cities of Switzerland, Sweden, Portugal, and Spain. The activity was especially intense in Madrid. There, American and British spies and diplomats helped downed Allied airmen fleeing over the border from France and worked to minimize the Spanish government’s help for the Nazis. And it was there in Madrid, early in 1944, that a twenty-three-year-old American fashion model named Aline Griffith (1920-2017) arrived as a neophyte OSS spy.

The Princess Spy: The True Story of World War II Spy Aline Griffith, Countess of Romanones by Larry Loftis (2021) 381 pages ★★★★☆

World War II was drawing to a close

Entering a hotbed of espionage

Griffith trained in spycraft at The Farm. She became adept at such arts as lockpicking, pickpocketing, and safecracking as well as ciphers and hand-to-hand combat. She was prepared for a battle she would never encounter. Griffith arrived in Spain only a few months before D-Day (June 6, 1944), which would lead to the end of the war in Europe in less than a year. But no one knew that then. Many military observers expected the fighting to continue into 1946 or ’47. And hundreds of Nazi agents representing the Abwehr, the Gestapo, and the Sicherheitsdienst worked in Nationalist Spain, sometimes openly supported by officials of Francisco Franco‘s government.

By contrast, the OSS had small numbers of agents in place, and the American ambassador disdained espionage. For American spies like Griffith, the challenges were immense. But Aline Griffith wasn’t destined to tangle with enemy agents or steal secrets. She worked under non-diplomatic cover as a code clerk for the American Oil Control Commission. And her job was to circulate in Spain’s high society and keep her eyes and ears open for signs of Nazi activity. In other words, listen for gossip.

Hobnobbing with European royalty

For the bright, vivacious, and beautiful former fashion model, the assignment was a natural. “In Madrid less than a day and already she had an admirer. A celebrity, no less.” It was Juanito Belmonte, one of Spain’s wealthiest and most famous bullfighters. He was the son of the legendary Juan Belmonte, who was “even more famous than Franco.” Juanito pursued Griffith for months. He took her to the capital’s most exclusive restaurants and night clubs and introduced her to celebrities from all across Europe.

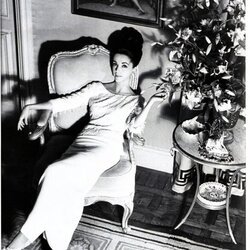

Soon, she was mingling with European royalty and attracting attention from other handsome, wealthy, and important men. She became a fashion icon, showcasing the dresses of Cristóbal Balenciaga and other haute couture designers. Griffith’s life was a whirlwind of elegant dinners, parties, and balls in the palatial homes of Spanish nobles. Her dates at these gatherings, and her friends, were Europe’s elite, some of them ardently pro-Nazi so long as Germany’s victory still looked plausible. And she proved adept at distilling meaningful intelligence from the gossip that swirled around her. Because not only had she worked as a runway model. She was also a college graduate and a quick study with a fine analytical mind that impressed her handlers in the OSS.

Finally, an assignment as a front-line agent

But it was not until February 1945 that Aline Griffith became what we would expect of an OSS spy: a field agent on dangerous assignments. The end of the war in Europe was three months away. The US government was concerned about the wealth and looted treasures that Nazi officials were flooding through Spain on their way to South America and other safe harbors. Griffith’s job was to identify the players in this high-stakes game and to learn how they moved their money. And that work continued long after the war in Europe officially drew to a close.

Even after President Truman shut down the OSS (September 20, 1945), Griffith continued to dog the footsteps of such suspects as Austrian Prince Maximilian Egon von Hohenlohe-Langenburg (1897-1968) and the Countess of Fürstenberg, née Gloria Rubio (1912-80). “The OSS was certain that Max had been getting money out of Spain, but it was up to Aline to figure out how and through whom.” That she did, working as an OSS spy in Project Safehaven (1944-48). She learned, though, that the Countess of Fürstenberg was not working for the Nazis, despite indications suggesting she was.

After the end of the war

Marrying into royalty

Some time after Juanito Belmonte faced the fact that Aline Griffith wasn’t in love with him, another suitor had surfaced. He was the handsome and fabulously wealthy Luis Figueroa y Pérez de Guzmán el Bueno, Count of Quintanilla (1918–1987). His grandfather was none other than Álvaro de Figueroa y Torres-Sotomayor (1863-1950), best known as the Count of Romanones. Figueroa was the former prime minister and principal adviser to the king before the Spanish Civil War.

Grandson Luis was dating her best friend but doggedly pursued Griffith nonetheless despite repeated brushoffs and missed dates because of her missions as a spy. Eventually, however, she agreed to marry him. (She had tried to tell him about her work as an OSS spy, but he refused to believe it was anything but fantasy.) The wedding took place in 1947. Years later, after the Count’s grandfather and father had both passed away, she gained the title Countess of Romanones. It was under that name that she gained fame in later years as a fashion icon and denizen of the international jet set. Her closest friends were the Duke and Duchess of Windsor and Audrey Hepburn and her husband, Mel Ferrer.

Continuing espionage after the OSS was disbanded

Loftis makes his most valuable contribution to our understanding of history in his account of the immediate post-war period. For two years, from the closure of the OSS on September 20, 1945 to the launch of the Central Intelligence Agency two years later (September 18, 1947), the United States no longer had a government-sanctioned foreign intelligence service. But Griffith and a small number of other tightly selected former OSS operatives kept working in Europe under private auspices.

With a blue-ribbon board of directors that included OSS Director William J. Donovan (1883-1959) and funding from the Mellon banking fortune, the man who had recruited Griffith to the OSS led a company called the World Commerce Corporation. He hired a number of the most successful OSS agents to continue work until the American government woke up to the necessity for a permanent spy agency. Aline Griffith was among the elect. It was under this private cover that she continued to track the transfer of Nazi-looted assets on their way out of Europe. And once the CIA came into existence, Griffith was called upon for “odd jobs” from time to time. (Records of those assignments remain classified.) The countess—never a princess, as the title claims—truly was a spy.

The sources of this story

During her long life—Aline Griffith was eighty-six years old when she died in 2017—she wrote five memoirs. Her books had titles like The Spy Wore Red (1987), The Spy Went Dancing (1990), and The Spy Wore Silk (1991). The books sold well. Unfortunately, they mixed fiction with fact. And the author of this nonfiction account caught her in lie after lie as his research progressed. She changed dates and hid the real names of many of those she worked with in the war, even “changing her own code name—from BUTCH to TIGER.” She also included fantastic accounts of gunfights and other adventures she never experienced. “Her spy books must be regarded as historical fiction; some parts are true, many others not.”

Still, the basic facts were there in the memoirs. Aline Griffith really did work as an intelligence agent from 1944 to 1947, including work as in the field for the OSS from February 1945 to August 15, 1945.” She continued to serve as an employee of World Commerce and for years afterward on special missions for the CIA. And “she was a highly productive and valuable agent, producing some fifty-nine field reports for the OSS, far more than any other Madrid agent, and had more subagents working for her than” all but two of her superiors.

About the author

Larry Loftis has published scholarly legal articles as well as two bestselling nonfiction books. The Princess Spy is the second of those books. He lives in Florida, where he practices law. Loftis holds a B.A. in Political Science and a J.D., both from the University of Florida.

For related reading

I’ve also reviewed Code Name: Lise: The True Story of the Woman Who Became World War II’s Most Highly Decorated Spy by Larry Loftis (A woman was World War II’s most highly decorated spy). It’s one of the books I featured in Female spies and saboteurs in World War II.

Also, be sure to check out:

- 10 top nonfiction books about World War II

- The 10 best novels about World War II

- 7 common misconceptions about World War II

- The 10 most consequential events of World War II

You might also enjoy my posts:

- The 10 top espionage novels

- 30 good nonfiction books about espionage

- Top 10 mystery and thriller series

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.