Sometime late in the 1980s, I was speaking with the CEO of a major Fortune 500 company. The conversation turned to the stock market and how poor a guide it was to the country’s economic health. He pointed to General Electric and its CEO, Jack Welch. The company had consistently been posting 15 percent annual increases in net profits, quarter after quarter. “Jack Welch,” he said, “is cooking the books. There is absolutely no way any company GE’s size could honestly be turning in such rosy results every quarter for years on end, through all the economy’s ups and downs.”

This misleading pattern was the result of the misguided policy of putting shareholders first, he explained. Now, more than three decades later, I understand exactly what Jack Welch was doing to pull that off. It’s the dominant theme in New York Times business journalist David Gelles’ eye-opening biography, The Man Who Broke Capitalism.

How Jack Welch destroyed GE by putting shareholders first

When Welch took charge of General Electric as Chief Executive Officer in 1981, he immediately proceeded to set aside the strategy that had made the company one of the world’s most successful and admired business enterprises. “During his tenure, GE posted annualized share price growth of about 21 percent a year,” Gelles notes. But the way he achieved that growth was catastrophic. The policies he put in place—policies faithfully pursued by his chosen successor—nearly drove the firm into bankruptcy.

“At its nadir,” Gelles writes, “GE needed a $139 billion rescue from the Obama administration and an eleventh-hour investment from Warren Buffett to stave off collapse.” Eventually, the company was removed from the Dow Jones Industrial Average as one of the nation’s bellwether businesses. In 2021, what was left of GE was broken into three smaller companies. And the policies Jack Welch pursued—downsizing, dealmaking, and financialization—became the hallmarks of Big Business in America, as CEOs throughout the land rushed to mimic the man Fortune called “The Manager of the Century.”

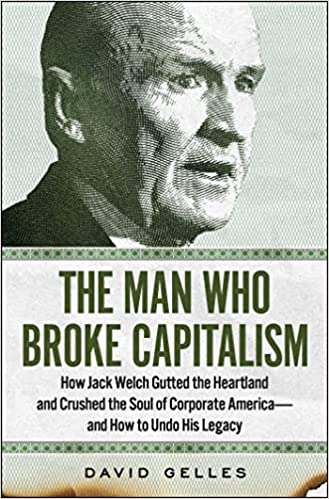

The Man Who Broke Capitalism: How Jack Welch Gutted the Heartland and Crushed the Soul of Corporate America—and How to Undo His Legacy by David Gelles (2022) 272 pages ★★★★☆

The avatar of shareholder primacy

A decade before Welch was named CEO, University of Chicago economist Milton Friedman had gained fame by insisting that the true purpose of any business was to make money for its shareholders. He dismissed talk of “the social responsibility of business” as “taxation without representation” for shareholders. Throughout the 1970s, other conservative economists and business school professors built on Friedman’s thesis. Putting shareholders first became a byword in conservative business circles. But in 1981 few if any large US corporations had put policies in place consistent with Friedman’s mandate. Jack Welch changed all that. He became the poster boy for shareholder primacy in the 1980s. And that misguided doctrine has dominated Big Business in America for the past four decades.

Downsizing, dealmaking, and financialization

Jack Welch gained the nickname “Neutron Jack” during the first four years of his tenure, when he divested 117 business units and slashed more than a quarter of the company’s jobs. But he continued to earn the reputation for the “rank and yank” policy he imposed on GE throughout his time as CEO. This was the practice of firing the 10 percent of employees who received the lowest annual performance reviews. And, in the process, Welch slashed funding for research and development, stifling the company’s well-earned plaudits for a century of innovation. After all, GE was the company of Thomas Edison. He also moved aggressively to spend billions of dollars buying back the stock, year after year, all in the interest of delivering value to shareholders. But, more broadly, Gelles views Welch’s strategy for GE as resting on three pillars.

Downsizing

“For generations,” Gelles notes, “it was generally true that once you got a job at a company like GE you could keep it until you retired.” In fact, Big Business, and the US economy as a whole, had prospered for decades grounded in this understanding. But “this was blasphemy to Welch.” The ink was barely dry on his employment contract when he launched a series of mass layoffs that shattered morale in the company’s workforce and set a pattern followed by other large corporations in the decades ahead. The jobs moved to new plants overseas, or to suppliers that were often overseas themselves, or simply disappeared. When Welch became CEO in 1981, GE employed some 400,000 workers. When he retired in 2001, the head count was down to 300,000 even after acquiring hundreds of companies during his 20 years at the helm.

Dealmaking

To meet Welch’s arbitrary profit targets, he and the men he commanded turned to acquisitions to fatten GE’s revenues and meet Wall Street’s rosy expectations. They spent $130 billion acquiring nearly 1,000 companies (including RCA and NBC). Many of these companies later proved to be hugely unprofitable—but they’d served their function by adding to the short-term bottom line. Which was entirely consistent with the commitment to put shareholders first. They’d also converted General Electric from a manufacturing company into a conglomerate dominated by its financial division, a massive unregulated bank called GE Capital.

Financialization

GE Capital was the centerpiece of Jack Welch’s strategy for the company. At the outset in 1981, the unit was a tiny operation that backstopped the company’s manufacturing businesses by financing customers’ purchases of GE appliances. Under Welch, GE Capital became the tail that wagged the dog, growing into a colossus with $370 billion in assets and “ultimately accounting for 40 percent of revenues and 60 percent of profits.” With worldwide operations, the unit grew into a multibillion-dollar bank that loaned money to retail customers and businesses alike from Romania to the Philippines.

“Thanks to the sprawling finance division,” Gelles writes, “[Welch] could produce ‘earnings on demand,’ as one analyst put it at the time . . . [I]n the last days of each quarter, GE Capital would often unleash a flurry of activity, adding profits and taking restructuring charges as needed to help the parent company meet Wall Street’s expectations.” At times, Welch went even further. “It even took to reporting growth in its pension fund’s investment portfolio as income.” All because Jack Welch had swallowed whole Milton Friedman’s theory that business operated best by putting shareholders first.

An icon for two generations of corporate managers

Throughout, Gelles emphasizes Welch’s far-ranging influence on the American economy as a whole. During his 20 years running GE, he was lionized in the press and regarded as a hero by millions. His impact on Big Business was immense. Welch trained hundreds of senior executives, and many of those “executives went on to lead dozens of other major companies—including Boeing, 3M, Honeywell, Chrysler, Home Depot, Albertsons, and many more—where they seeded new clusters, spreading Welchism across the whole of corporate America.” And we live today paying the steep price of that legacy.

About the author

The bio on David Gelles‘s author website reads in part: “David is a reporter for the Climate desk and the Corner Office columnist for the New York Times. At the Times, he previously covered mergers and acquisitions for DealBook. Before joining the Times in 2013, he spent five years with the Financial Times. At the FT, he covered tech, media and M&A in San Francisco and New York. In 2011 he conducted an exclusive jailhouse interview with Bernie Madoff, shedding new light on the $65 billion ponzi scheme. He lives in New York City with his family.”

For more reading

You’ll find books about related topics at:

- My 10 favorite books about business history

- Great biographies I’ve reviewed: my 10 favorites

- Good books about finance and economics

- Top 20 popular books for understanding American history

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, plus a guide to this whole site, on the Home Page.