The tides of otherism have ebbed and flowed throughout five centuries of American history. Racism. Antisemitism. Xenophobia. From the genocide of the continent’s native peoples, to the enslavement of millions of transplanted Africans, to the Know-Nothing fury toward Irish immigrants and Catholics, to the racist violence and perversions of justice under Jim Crow, the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the internment of Japanese-Americans during World War II, and the exclusionary policies of the Trump Administration, the fear, ignorance, and insecurity that give rise to otherism have always been with us. Now, in The Guarded Gate, Daniel Okrent surveys one slice of this sad history by examining the racist movement that effectively halted immigration a century ago. He does so with lucid prose and a meticulous appraisal of the facts.

Estimated reading time: 9 minutes

The Guarded Gate: Bigotry, Eugenics, and the Law That Kept Generations of Jews, Italians, and Other European Immigrants Out of America by Daniel Okrent (2019) 497 pages ★★★★★

America has always been “a nation of immigrants”

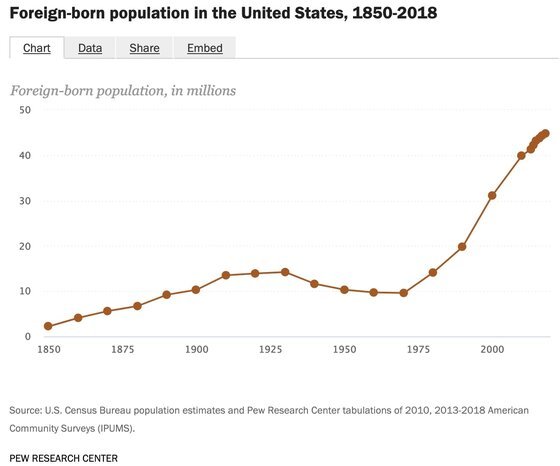

John F. Kennedy elevated the familiar phrase into public discourse with the title of his final book. It is, of course, true by definition that only a vanishingly small proportion of the American people are descended from natives—and even they emigrated to North America some twelve to fourteen thousand years ago. But immigrants have come to the United States in waves. Germans and Irish in the middle of the nineteenth century. Southern and Eastern Europeans in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Latinx and Asians beginning later in the twentieth century and accelerating since the 1970s. But the wave of new Americans who set off the backlash that is Daniel Okrent’s subject in The Guarded Gate arrived during the period 1892 to 1924.

During those three decades, the immigrant tide became a flood. And, as Okrent notes, “in 1882 fewer than 15 percent of European immigrants came from the regions east of Germany and south of present-day Austria. Then everything changed.” For example, “by 1900 more than 400,000 Bostonians, out of a population of 560,000, had at least one foreign-born parent.” And the overwhelming majority of those parents were Italians, Russian or Polish Jews, or others from the eastern and southern reaches of Europe.

An in-depth study of the Immigration Act of 1924

The Immigration Restriction Act of 1924, known as the Johnson-Reed Act, was the culmination of the three-decade history that Daniel Okrent surveys in this probing study. His story begins in 1892, when Senator Henry Cabot Lodge (1850-1924) introduced the first of his many attempts to insert a literacy test into the requirements for admission to the United States. Despite Lodge’s fanatic persistence from 1892 to 1920, and the obsessive and well-funded arguments by others in the northeastern Protestant establishment, the literacy test was rejected by four Presidents, three of them Republicans like Lodge. William McKinley, Theodore Roosevelt, and William Howard Taft all vetoed any bill that came to their desks if it contained the literacy test, as did Democrat Woodrow Wilson after them.

But the decades-long struggle over the literacy test proved to be a warmup act. The passions unleashed by the First World War and the rising influence of “scientific racism” enabled something much worse: the near-total prohibition of immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe that the Johnson-Reed Act required. Sadly, the movement also succeeded in enacting into law in many states the practice “of involuntary vasectomy or tubal ligation of prisoners, mental asylum inmates, and others ‘under state control.'” Sterilization, in other words.

The racist movement was grounded in eugenics

Eugenics, the “science” in “scientific racism,” was a perversion of Mendel’s findings on genetics and Darwin’s theory of evolution. It originated in early twentieth-century England but found its full flowering in the United States—and later in Nazi Germany. By elevating anecdotal and impressionistic observations into “data” and drawing foregone conclusions from them, the proponents of eugenics argued that Italian and Eastern European immigrants were inferior to what at the time were called “native Americans.” To “improve the genetic quality” of the American population, they insisted, it was necessary to bar admission to people from those regions. They got their wish in 1924. And the bill they forced through Congress was not repealed until 1965. (The Chinese Exclusion Act was revoked in 1943, when China fought as a US ally in World War II.)

Pseudoscience?

Calling eugenics a pseudoscience is much too polite. Its practitioners and advocates were far from polite when they used such phrases as “vast masses of filth . . . living like swine,” “the scum, the offal, and the excrescence of the earth,” and “morons” to describe the people they were so eager to exclude from the United States. But this was not crackpot science out on the fringe of respectable society. It was crackpot science cradled within the bosom of the American scientific establishment. And this overtly racist movement was championed by the American Federation of Labor, the influential Saturday Evening Post and the editorial page of the New York Times, and many of the country’s leading citizens, including Margaret Sanger (1879-1966) and Walter Lippman (1889-1974).

Wishful thinking spurred on by racism

Researchers whose meticulous studies of genetic variations in fruit flies and poultry would win them generous grants and awards, including the Nobel Prize, wandered off into the Never-Neverland of conjecture and wishful thinking spurred on by racist convictions. They possessed all the intellectual integrity of today’s Right-Wing talk radio hosts and online conspiracy theorists. Some of the “research” on which the eugenicists’ arguments were based consisted of administering written intelligence tests in English to illiterate Italian and Eastern European immigrants who had never before in their lives held a pencil in their hands.

How, then, could the members of the House and Senate be swayed by their arguments? Okrent explains that “‘facts’ gathered by [their] methods were readily available, and no matter how irrelevant or misconstrued or flimsy they were, they could make a for a sturdy edifice when presented by a credentialed expert brandishing seemingly authoritative data.”

Three influential European forebears for America’s racist movement

Three Europeans laid the foundation for the “science” on which American xenophobia was based. The English polymath Sir Francis Galton (1822-1911), a pioneer of eugenics—he coined the term, shared a grandfather with Charles Darwin. French novelist Arthur de Gobineau developed the theory of the Aryan master race. And British-born German philosopher Houston Stewart Chamberlain (1855-1927) was the author of work that later influenced the antisemitism of Nazi racial policy.

The chief American actors

Okrent traces the strength of the anti-immigration movement during this period to the work of a handful of individuals, Senator Lodge among them, and to the publication of several influential books. Among the key individuals, many of them Boston Brahmins like Lodge, were:

- Prescott F. Hall (1868-1921) was one of the founders and first secretary of the Immigration Restriction League, today considered the first anti-immigrant think tank in the United States. “Over time,” Okrent writes, Hall “would probably devote more hours, more effort, and more complete conviction to stopping immigration than any other individual.”

- Thomas Bailey Aldrich (1835-1907) actively urged on the rising tide of anger directed toward immigrants in the pages of the Atlantic Monthly, which he edited.

- Joe Lee (1901-91) was a prominent Boston philanthropist and Democratic politician who founded the playground movement in America and generously supported charities throughout his home town but also bankrolled the racist anti-immigration movement.

- Biologist Charles Davenport (1866-1944) sheltered pseudoscientific “research” at the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, where he founded the Eugenics Record Office in 1910.

- Madison Grant (1865-1937)’s 1916 book, The Passing of the Great Race, fueled the anti-immigrant wave a century ago and, sadly, is still cited today as an inspiration by racists who may never have actually read it.

- Paleontologist Fairfield Osborn (1857-1935) served as president of the American Museum of Natural History for 25 years. There, he hosted many of the most important meetings of the elite activists who directed the anti-immigrant movement.

Okrent’s account of the growth of xenophobic sentiment in the runup to the passage of the 1924 Immigration Act is richly textured and abounds with fascinating, often confounding personalities. It’s a deeply moving study of how sometimes highly intelligent and well-educated men and women could veer off into fantasy under the influence of deep-seated prejudice and peer pressure. And it demonstrates just how pervasive racism has been in the long and often tragic history of the United States.

About the author

Daniel Okrent (born 1948) was the first public editor of The New York Times. He has been an editor at publishing houses and magazines as well as the Times during most of his career. He is the author, co-author, or editor of eight books but may be best known (to some) as the inventor of the most popular form of fantasy baseball.

For related reading

I’ve reviewed an excellent book that follows the immigration debate through the passage of the 1965 law that overturned the Johnson-Reed Act discussed in this book: One Mighty and Irresistible Tide: The Epic Struggle Over American Immigration, 1924-1965 by Jia Lynn Yang (What has made America a nation of immigrants?).

To explore related subjects, check out:

- Good books about racism

- “The Rest of Us”: The Rise of America’s Eastern European Jews by Stephen Birmingham (Start here to understand Jews in America)

- The Imperial Cruise: A Secret History of Empire and War (James Bradley—Teddy Roosevelt and the dark side of American foreign policy)

- The Jews: Story of a People by Howard Fast (An account of Jewish history full of surprises)

You might also be interested in Top 20 popular books for understanding American history and 20 top nonfiction books about history.

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.