Estimated reading time: 8 minutes

On October 12, 1964, a prominent Washington socialite named Mary Pinchot Meyer was shot to death on the towpath along the C&O Canal in storied Georgetown. An African-American man spotted there was arrested for her murder, but no compelling evidence ever surfaced to support his conviction, and he was acquitted at trial. The case attracted a torrent of press attention when it became clear that the murdered woman was President John F. Kennedy’s lover.

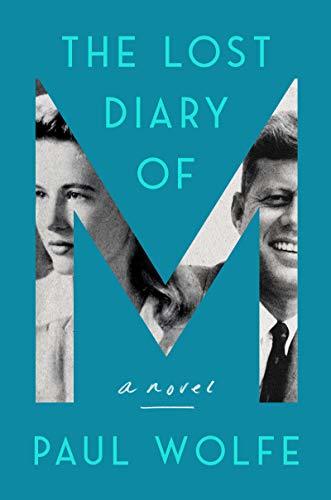

Then, nearly half a century later, a psychologist and lecturer named Peter Janney published Mary’s Mosaic, a deeply researched inquiry into the circumstances surrounding Mary Meyer’s death. His was just the latest in a long series of articles and books about the murder, but Janney’s findings were explosive. They centered around a diary Mary was known to have been keeping that revealed her passionate affair with President John F. Kennedy. Now, in his second novel, Paul Wolfe cleverly imagines what Mary wrote in that book and how she came to be murdered.

The Lost Diary of M by Paul Wolfe (2020) 304 pages ★★★★★

What history knows about John F. Kennedy’s lover

Mary Pinchot Meyer was a daughter of the Northeastern elite that for so long had played a dominant role in the American economy, culture, and government. She herself took up painting and joined the abstract expressionist Washington Color School as a student of Kenneth Noland. Some of her paintings hang in museums today.

- Mary’s uncle was Gifford Pinchot (1865-1946), confidante of President Theodore Roosevelt, first chief of the United States Forest Service, and later Governor of Pennsylvania. Her father, Amos Pinchot (1873-1944), was a lawyer and prominent progressive reformer in the 1920s.

- Her sister, Toni, married Ben Bradlee (1921-2014), who rose to fame as the executive editor of the Washington Post and managed its coverage of the Pentagon Papers and the Watergate scandal.

- Mary herself attended the elite Brearley School and Vassar College, where many of her classmates became involved in the Washington elite through marriage.

- Immediately after World War II, Mary married Cord Meyer (1920-2001), and together they built the United World Federalists. Later, Cord joined the fledgling CIA, where he shed his liberal idealism and served in senior roles until 1977.

- One of Cord’s bosses, James Jesus Angleton (1917-87), the notorious head of counterintelligence for the CIA, became godfather to two of their children.

Mary’s 30-year relationship with John F. Kennedy

Mary Pinchot was attending a school dance in 1937 when an impertinent young man named John Kennedy repeatedly tried to cut in on her and her date. It was impossible not to know who Kennedy was; his already famous father, multimillionaire businessman and Hollywood producer Joseph P. Kennedy (1888-1969), was named US Ambassador to the United Kingdom the following year. But Mary was offended by the young man’s advance and apparently had no contact with him for more than a decade.

Not until after he emerged from World War II as a hero and was elected, first to Congress and then to the United States Senate. He was already married to Jacqueline Bouvier (1929-94). But, always on the prowl, Kennedy pursued her despite his marriage. Her resistance melted over time, and after he was elected President she agreed to join him for “dates” in the White House. Not much time passed before the two were in love. Contemporary accounts support this assertion and suggest that Kennedy would have divorced Jackie after serving his second term in office. Mary Pinchot Meyer, John F. Kennedy’s lover, was to become his second wife.

A story filled with bold-faced names

In Paul Wolfe’s telling, and in established fact, Mary’s life in Washington was a continual whirl of Georgetown cocktail parties, casual liaisons, and an unending torrent of the rumors that swirled around the Kennedy Administration.

“Girlfriends”

Mary’s “girlfriends” included her sister, Antoinette (Toni) Bradlee, wife of the Washington Post‘s executive editor; Katherine Graham (1917-2001), later her husband’s successor as publisher of the Washington Post following his suicide; Cicely (Ceci) Harriet d’Autremont Angleton, wife of James Jesus Angleton; Polly Wisner, who was married to one of the CIA’s founding members; and Pamela Harriman (1920-97), formerly Winston Churchill’s daughter-in-law and then married to Averell Harriman, a prominent State Department official and one of the country’s wealthiest men.

Partygoers

The men who frequented the Georgetown parties where gossip flowed as freely as liquor included her then ex-husband, Cord Meyer; Cord’s mentor and boss, James Jesus Angleton; Frank Wisner (1909-65), a former CIA Director close to Angleton; Phil Graham (1915-63), publisher and later co-owner of the Washington Post; Ben Bradlee; and even, occasionally, John F. Kennedy.

In the White House

Once Mary’s intense affair with Jack Kennedy was underway, she interacted frequently with Kenneth O’Donnell (1924-77), the President’s Appointments Secretary (and procurer). She had little or no contact with others in the White House, since O’Donnell whisked her in and out in secrecy. Unlike so many other women during the three short years of the Administration, Mary Meyer, was John F. Kennedy’s lover in reality and not a one-night fling.

A tale of love, lust, and LSD

In The Lost Diary of M as well as in journalistic accounts, Mary Meyer’s life during the Kennedy Administration revolved around her painting, the two young sons she shared with Cord Meyer, the gossip mill of the Georgetown set, her love affair with the President—and her experimentation with LSD. In Wolfe’s tale, Mary “drops acid” with the poet Allen Ginsberg in California and then resolves to enlist Timothy Leary in “turning on” her girlfriends in Georgetown.

A lifelong pacifist, descendant of a long line of Pinchot pacifists, Mary regards LSD as the means by which she and her friends will convert the powerful men of the Administration to the cause of world peace. And she does, in fact, manage to persuade several of the women she knows not only to take LSD themselves but to administer it to their husbands—with no apparent effect. She does eventually succeed in enticing the President to experience the drug—and shortly afterward, Kennedy delivers a ringing plea for world peace in a widely cited commencement address at American University (June 10, 1963) that shocked the Pentagon and the State Department. Mary, or rather Paul Wolfe, imagines a direct connection between the LSD and the call for peace.

Mary regards that speech—and, even more tellingly, his decision not to authorize support for the invading force at the Bay of Pigs—as the reasons for his assassination. And it becomes clear in the pages of her diary that the events of November 22, 1963, were the doing of the CIA. Peter Janney’s book makes the same case, and (in my view) he does so convincingly.

Whatever became of the diary?

By all accounts, there was, indeed, a diary. As Paul Wolfe imagines it, James Jesus Angleton breaks into Mary’s home the day of her murder and steals the diary. In other accounts, Angleton turns over the diary to Mary’s sister, Toni, and her husband, Ben Bradlee. But, whoever it is who decides to hide or destroy the book, it does disappear. The diary has never resurfaced in the nearly sixty years since Mary’s murder.

About the author

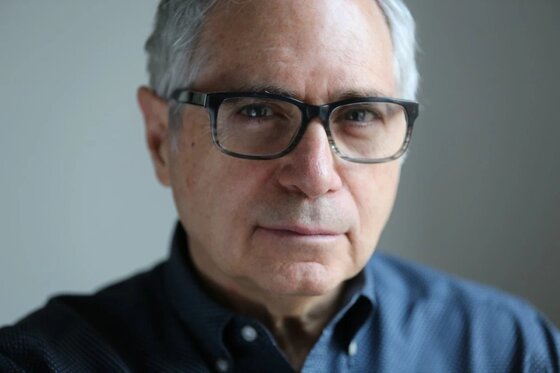

Paul Wolfe‘s biographical blurb on Amazon, widely quoted elsewhere, states that he “has written in virtually every medium, from fiction and advertising to songs and plays.” The Lost Diary of M is his second novel.

For related reading

This is one of The best books of 2021 and the 10 best historical novels set in America.

Be sure to check out Mary’s Mosaic: The CIA Conspiracy to Murder John F. Kennedy, Mary Pinchot Meyer, and Their Vision for World Peace by Peter Janney (Why did JFK die? The most convincing explanation I’ve ever read). It’s a journalistic account of how John F. Kennedy’s lover helped steer him on a course for peace.

For other alternative perspectives, see 11/22/63 by Stephen King (Stephen King’s take on the JFK assassination) and Surrounded by Enemies by Bryce Zabel (What if JFK had survived Dallas?).

You might also be interested in:

- The Devil’s Chessboard: Allen Dulles, the CIA, and the Rise of America’s Secret Government by David Talbot (When America’s secret government ran amok)

- Top 20 popular books for understanding American history

- 11/22/63 by Stephen King (A new take on the JFK assassination)

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.