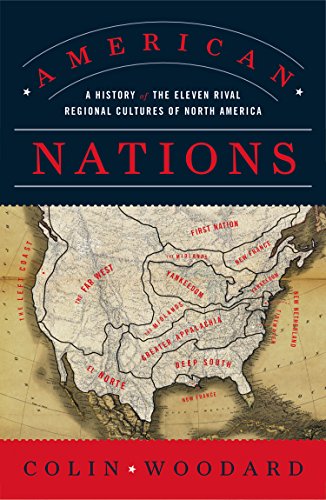

Does the Red State-Blue State analysis of recent US elections make sense to you? Or pointing to the difference between Republicans and Democrats to explain election outcomes? Colin Woodward doesn’t think either one is useful in explaining how and why we vote as we do. Nor, in his opinion, are the boundaries that define our fifty states or the regions normally termed Northeast, Midwest, South, and so forth. None of these arbitrary distinctions stand up to scrutiny in light of the cultural history he relates so beautifully in his eye-opening book, American Nations. To understand polarization as it defines the American project today, reading this book is a must.

American “Nations?” Here’s what that title means

The key to this book lies in the distinction between the terms “nation” and “state.” Woodard examines the confusion at the outset. We Americans, he writes, “are among the only people in the world who use statehood and nationhood interchangeably. A state is a sovereign political entity like the United Kingdom . . . A nation is a group of people who share—or believe they share—a common culture, ethnic origin, language, historical experience, artifacts, and symbols. Some nations are presently stateless—the Kurdish, Palestinian, or Quebecois nations, for instance. Some control and dominate their own nation-state, which they typically name for themselves, as in France, Germany, Japan, or Turkey.”

American Nations: A History of the Eleven Rival Regional Cultures of North America by Colin Woodard (2011) 386 pages ★★★★★

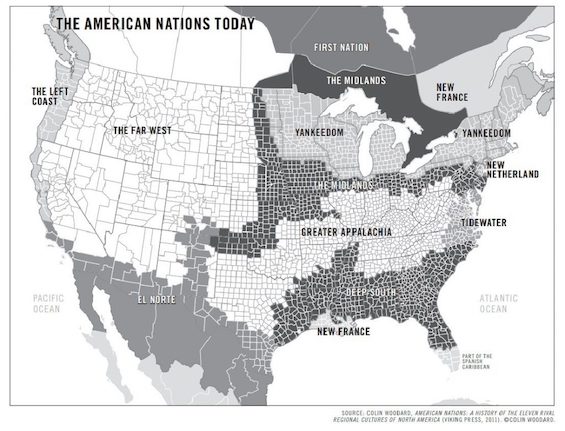

When we view American history and attempt to understand polarization through the lens of this distinction, the American state proves to be a mosaic of eleven distinct nations, several of which are not contained exclusively within the current US borders but blend into both Mexico and Canada.

To understand polarization, look to the origins of European settlement in America

The gist of Woodard’s argument is that the earliest European settlements in North America established cultural and political patterns that held more or less true over the following centuries. This, despite the massive immigration that accounts for fully one-half of the American population today—because as population shifted westward across the continent, people relocated to communities where they found others who shared their values and worldview. And, for the most part, newly arrived immigrants fell under the sway of existing cultural patterns where they landed rather than imprinting their own values on those who came before.

In short, “it is fruitless to search for the characteristics of an ‘American’ identity, because each nation has its own notion of what being American should be.”

A closer look at the Revolution and the Civil War

Woodard’s analysis accounts for much of the confusion that arises under the surface of popular accounts of both the Revolution and the Civil War. Sweeping away that confusion will help you understand polarization as it defines American politics today.

- It’s often said that one-third of those in the Thirteen Colonies supported the Revolution, one-third opposed it, and one-third were neutral. But this simplistic notion fails to account for what really happened. “Some nations—the Midlands [most of New Jersey and Pennsylvania], New Netherland [principally New York City and northern New Jersey], and New France [then just northern Maine]— didn’t rebel at all. Those that did weren’t fighting a revolution; they were fighting separate wars of colonial liberation . . . [and] the four nations that did rebel—Yankeedom [New England], Tidewater [coastal North Carolina, Virginia, and Maryland], Greater Appalachia, and the Deep South—had little in common and deeply distrusted one another.” And “Georgia even rejoined the empire” in 1779. In other words, there was neither an American state nor—much less—an American nation before the ratification of the Bill of Rights in 1791.

- What some still insist on calling the War Between the States was, similarly, far more complex than it is generally pictured. “The Civil War era has long been portrayed as a struggle between ‘the North’ and ‘the South,'” Woodard notes, “two regions that, culturally and politically, didn’t actually exist.” Instead, “the Civil War was ultimately a conflict between two coalitions. On one side was the Deep South and its satellite, Tidewater; on the other, Yankeedom. The other nations wanted to remain neutral, and considered breaking off to form their own confederations, freed from slave lords and Yankees alike.”

A struggle between two ethnoregional coalitions

Just as the Civil War was a struggle between two coalitions among the eleven American nations, the seminal events of the following century and a half can be similarly explained. “While a Dixie bloc was coalescing around individual salvation and the defense of traditional social values,” Woodard asserts, “a Northern alliance was forming around a very different set of religious priorities. It was spearheaded by the clergy and intellectual elite of Yankeedom, but it found a ready audience across the Midlands, the Left Coast, and New Netherland. From the time of the Puritans, the Yankee religious ethic focused on the salvation of society, not of the individual.” And this focus lies behind the “liberal” mandate to “try to make the world a more perfect and less sinful place.”

As Woodard explains, Temperance, Prohibition, and the turn-of-the-century crusades to ensure the welfare of children were all driven almost entirely by Yankees and Midlanders, with New Netherlanders also prominent in the struggle for women’s suffrage. Later, “Northern alliance campaigns for civil liberties, sexual freedom, women’s rights, gay rights, and environmental protection all became divisive sectional issues, just as Dixie’s promotion of creationism, school prayer, abstinence-only sex education, abortion bans, and state’s rights did.”

So, instead of looking to the Red State-Blue State model, or an analysis based on the traditional geographic regions, to understand American politics, Woodard offers an alternative. “Ultimately,” he writes, “the determinative political struggle has been a clash between shifting coalitions of ethnoregional nations, one invariably headed by the Deep South, the other by Yankeedom.” To my mind, Woodard’s approach makes a great deal more sense. It’s the only way I’ve found to understand the polarization that has led to the ascendancy of the Radical Right.

What reviewers said about this book

Although this book wasn’t widely reviewed upon its publication, two prominent sources of criticism both found it engaging and worthy. Writing in the Washington Post (November 18, 2011), Alec MacGillis described American Nations as “a compelling and informative attempt to make sense of the regional divides in North America.” And Publishers Weekly (September 2011) declared that “the book’s compelling explanations and apt descriptions will fascinate anyone with an interest in politics, regional culture, or history.”

About the author

Colin Woodard is a Maine-based journalist and author. He is State & National Affairs Writer at the Portland Press Herald and Maine Sunday Telegram. He received a 2012 George Polk Award for an investigative project he did for those papers and was also a finalist for the 2016 Pulitzer Prize for Explanatory Reporting. American Nations was the fourth of his five books.

For further reading

A fascinating essay entitled “The Four Americas” by journalist Joe Klein appeared in the New York Times Book Review on October 17, 2021. It’s based on a 946-page book published in 1989 by David Hackett Fischer, Albion’s Seed: Four British Folkways in America. The book approaches much the same subject as Woodard’s but reaches slightly different conclusions.

For a pessimistic view of the consequences of the disunity Woodard portrays, see The Next Civil War: Dispatches from the American Future by Stephen Marche (Is a new American civil war inevitable?).

You might also be interested in:

- Top 20 popular books for understanding American history

- Top 10 nonfiction books about politics (plus dozens of runners-up)

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, plus a guide to this whole site, on the Home Page.